Everything you need to know about watch finishing

Borna BošnjakLooking for a singular resource on all the watch finishing techniques you should ever be familiar with? Look no further, as we try to list every polishing, brushing and dial-creating process we knew of and could come across. Ctrl+F away, dear reader.

Anglage

Anglage, bevelling or chamfering, describes a movement finishing technique in which the right-angled edges of the bridges, plates and other components are filed and polished at a 45-degree angle. Masters of this technique are the likes of Philippe Dufour, Rexhep Rexhepi and Romain Gauthier, who add a degree of complexity with perfectly executed inward angles. These are even more difficult to create as there needs to be a uniform, sharp line separating the curved edge of the chamfer. Anglage is often combined with contour grinding, which leaves the polished chamfer as a highlight between two non-reflective surfaces.

Azurage

The azurage finish is most commonly seen on dials, where overlapping patterns of concentric circles create an illusion of moving waves. This technique is often seen in sub-dials, like on the Zenith above, but also across entire dials of watches like the TAG Heuer Carrera.

Bluing

Bluing is a process applied to steel components, most commonly found on watch hands and screws. Proper heat-bluing or tempering is a complicated process that requires a multi-step process, including careful and consistent temperature control, as that is what will determine the regularity of the colour and the colour itself.

Bluing can also be done chemically, usually resulting in more consistent product, but does not produce the same sheen and depth of colour that heat bluing does, and is generally not as well-regarded as heat bluing. For an in-depth look at bluing, Henrik Korpela of the K&H Watchmaking Competence Centre explains more in this SJX article.

Brushing

Brushing is an umbrella term for many different types of watch finishing that marks a surface with very fine etching, creating a non-reflective finish akin to that of brushstrokes. Common types of brushing include linear, circular and sunburst, where the lines emanate from the centre to create a sunray-like pattern.

Some variations on the theme include Glashütte sunburst brushing colimaçonnage and snailing, where the lines of a regular sunburst pattern are curved or change direction midway through the process.

Enamelling

By combining silica glass with a variety of other elements, painting it onto blanks of copper, gold and other metals before firing in kilns at many degrees Celsius, we get what are known as enamel dials. The craft that was discovered some 4,000 years ago is to this day considered one of pure artistry, with only a few masters being able to produce these highly complicated artworks. Enamel dials come in many forms, so let’s explore them below.

Grand feu is likely the simplest to explain, but at the same time, most sought-after forms of enamelling. Literally “great fire”, the technique is named after the burst of flames from the alcohol-treated powdery surface as it enters the kiln. Beginning with a dial blank larger than the final product, curved at the edges to stop the liquid glass from running off, the enamel powder is sprinkled on evenly, before being sprayed with alcohol to prevent the powder from being disturbed on its way to the oven. At a minimum of 700 degress Celsius, the process is repeated several times, with a fresh sprinkling of powder each time. A diamond tool is used to cut the holes for any pinions, and is a risky process as the enamel is prone to cracks. The RRCC above showcases another consideration, where any sunken sub-dials need to be created separately, and then fitted into the larger dial. Though many modern makers use pad-printing, grand feu enamel dials traditionally had hand-painted markers and indices.

Champlevé enamel combines techniques of engraving and enamelling, where grooves will be cut into the dial blank, like in the solid silver dial of the Lang & Heyne above, before being filled with enamel. The artisan will leave the raised edges of the engraved metal exposed, creating a dichotomy between the metallic edges of the engravings and vitreous quality of the enamel.

A close relative to champlevé enamel is flinqué. Using an intricate guilloché base, the enameller will paint the enamel onto the dial, mixed in with different colourings. Like with many other types of enamel, different stages of firing are in order, with an additional enamel layer added between each firing. The effect leaves a translucent layer over the rose engine-carved dial, an effect that cannot be replicated in any other way.

Cloisonné is sure to vie for the title of “most annoying and complicated to execute” enamel technique with the next entry on the list. Using a thin, usually precious metal, wire, the artisan bends it into a shape of a pre-drawn pattern – you can see the thin gold lines separating the colours in the Vacheron Constantin above. This technique allows the artisans to create stronger colour separations, allowing for more accurate scenes, often depicting maps, flora, and fauna themes.

If you had the chance to visit any older church, especially in Europe, you would’ve come across a stained glass window. Colouring their vaulted alcoves and ceilings, they’re a signature feature of many Christian establishments. Plique-à-jour is essentially the same thing, only on a miniature scale, executed with enamel. It uses golden wire, much like cloisonné, but without a solid dial base, meaning the enamel is suspended in its metal cells, as light is allowed to pass through.

From bright and colourful, we take to grisaille enamel. The grisaille technique begins with a layer of black enamel, before applying blanc de Limoges paint that uses porcelain powder. Rather than melting once fired like enamel, the white paint adds layers, creating an amplified three-dimensional effect in dramatic monochrome, allowing for great textural detail seen here in the falcon’s feathers.

Jaquet Droz could’ve appeared in every example of enamelling techniques, but I could not exclude their execution of paillonné enamel. Before applying any enamel, an engraver applies a guilloché sunburst pattern to the dial, so this is a pseudo-flinqué enamel dial as well. Once the first layer is fired at grand feu enamel temperatures, thin gold leaves are applied to create intricate patterns, as seen above from the Fleur de Lys and Fleur de Vie patterns. To seal them in place, another layer of translucent enamel is applied, holding the micron-thin gold appliques in suspension.

Set against a grand feu enamel backdrop, hand-painted enamel recreations originally rendered on paper require a completely different set of skills. The techniques that work to create certain effects on paper or woodblock need to be completely re-worked to achieve the same when painting on enamel, and will be different depending on the colours used.

Engraving

Engraving is relatively self-explanatory, though it is split into two categories. The Kudoke above is engraved by a chisel that removes excess material, the raised ridges making up the organic shapes of the pattern – sometimes called chasing.

On the flip side, akin to this Franck Muller, the engraver can form grooves in the metal that become the pattern, which is the more common form of engraving. While guilloché does fall under this category, I felt that it deserved a heading of its own.

Frosting

A frosted surface has the appearance of well, being covered in frost. This is usually achieved with media blasting with more affordable watches, while rare high-end pieces are frosted manually. The MB&F LM 101 Frost above uses a series of burnishes to create the patterned surface, compressing the metal without removing any of it, a pattern that’s impossible to hand-engrave.

Tremblage is a technique that allows for a frosted pattern, though here, the artisan burin-engraves the dial with thousands of tiny, uniform engravings that create a glistening pattern.

In the case of the Grönefeld Parallax Tourbillon, this same tremblage effect is achieved with a hammer and chisel, rather than a burin.

Finally, we have grenaillage, an effect used by Blancpain in their L-evolution C Tourbillon Carrousel. Pioneered in the late 18th century, grenaillage was initially used for its anti-corrosive properties, rather than decoration. Rather than using gold and mercury, Blancpain achieves the dark, frosted finishing through a galvanising process.

Guilloché

The Clous de Paris or hobnail pattern almost deserves its own entry, rather than relegating it to the guilloché category. Combining engraving and guilloché work, the result is a pattern of small, regular square protrusions, separated by engraved grooves separating the raised sections. The most popular execution of this style can be found in Patek Philippe’s Calatrava, where it appears as a dual row of tiny pyramids around the bezel.

Taking out three guilloché patterns with one dial is this stunning Voutilainen, featuring barleycorn or grain d’orge, wave and hobnail motifs. True manual guilloché is created with a rose engine, the number of which has dwindled over the years, by creating a series of small, repeated grooves and with a helping heap of patience.

Audemars Piguet is well-known for popularising the tapisserie guilloché pattern that appears on most of their Royal Oak models, and is an adaptation of the Clous de Paris motif, with repeated small squares separated by textured channels. As for watches at lower price points that feature guilloché dials, these are often results of stamped processes.

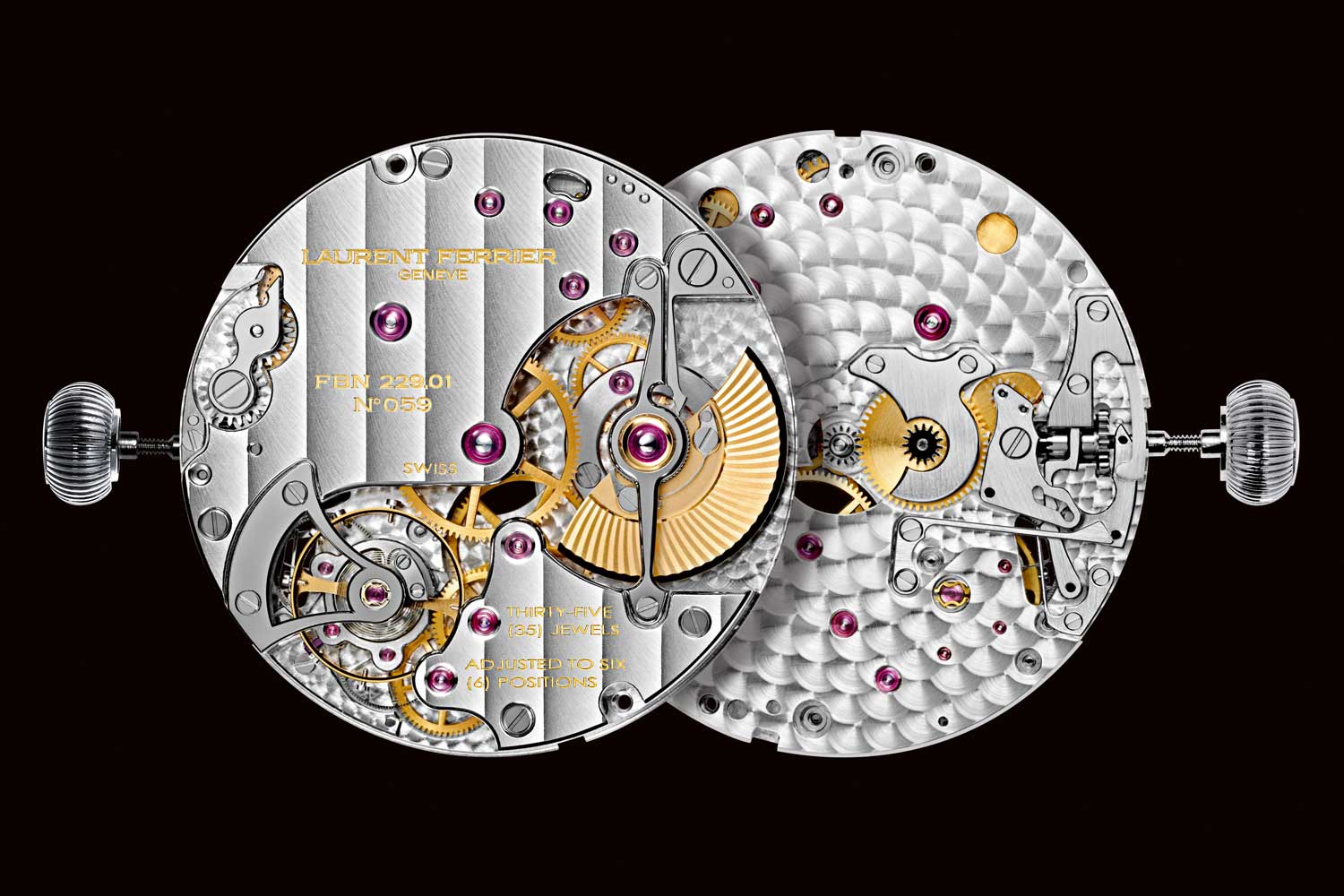

Perlage

Perlage is among the most commonly seen forms of movement decoration, also referred to as circular graining. Whether you go fully traditional, with a wooden rod and wet sanding paste, or a modern abrasive pad and machine that spins it, regular and uniform pearls are difficult to achieve.

Plating

Most watch movements use brass for the base material of its bridges and plates, so to soup up their appearance, different types of plating may be applied. Gold, or gilded (gilt) plating, nickel plating and rhodium plating is most common, as they all have visual characteristics of precious metals, but cut down costs significantly. Vintage Omega movements often used copper plating for that signature red finish.

Polishing

Polishing comes in many forms, but all are in the shadow of mirror, flat or black polishing. As demonstrated by the most impressively finished watches, black polishing leaves a spotless, blemish-free surface that is so reflective that it appears black at certain angles. Achieved by a uniform, circular or figure-of-eight rubbing motion against progressively less granular diamond pastes, and naturally, has to be done by hand.

I could not move onto the next item without at least a brief mention of Zaratsu polishing, a finish popularised by Grand Seiko, involving flat, distortion-free polished surfaces of the cases and dial indices. Essentially, it can be explained as an industrial derivative of black polishing.

Sinks

In order to further highlight the flat-polished screw heads holding in the various components, or the often gold chatons holding the jewels, watchmakers create a concave groove that is then black polished. This also allows the screws to sit completely flush in their (counter)sinks, and with the rest of the movement components if necessary.

Skeletonisation/openworking

Skeletonisation and openworking are often confused to be one and the same, even though that’s not necessarily true. Skeletonisation is indeed the tradition of displaying the inner workings through openings in the dial and movement components, but these movements are often created that way from the get-go.

View this post on Instagram

Masters that take movements not originally designed to be skeletonised and then carving their way and leaving as much as possible exposed are much less common, with this practice referred to as openworking. The example above is Felipe Pikullik’s attempt at openworking a workhorse Unitas calibre.

Striping

As we come to a close of this (hopefully) comprehensive write-up, we reach one of the best-known movement decoration methods. Geneva striping or Côtes de Genève appear in everything from entry-level calibres from the Swatch Group to the most avant-garde, modelled here by a stunning JLC from their Master collection. Created either with a wooden cutting tool that creates the textured finish, or with a lathe, some claim they were initially created to trap dust and particles, though many watchmakers disagree, naming them as purely decorative.

An alternative finishing technique would be Glashütte striping or ribbing, and though some German watchmakers claim them to be distinctive from their southern variant, they’re generally one and the same.