Grand Seiko Manufacture Tour Part 2: The Seiko Museum in Ginza

Zach BlassAfter having a blast in Morioka, getting intimate with all things Grand Seiko 9S mechanical at Studio Shizukuishi, we returned to Ginza to check out a few sites heavily tied with the Seiko Corporation – the first of which being the Seiko Museum Ginza. There is no better place in the world to visit to best understand all that is Seiko, with six themed floors dedicated to not only the entire history of Seiko but also the history of timekeeping overall. To put it in perspective, the museum presides over nearly 30,000 items – with approximately 10,000 watches and 1,800 clocks, 250 traditional Japanese clocks, 250 paintings, and 16,000 books, magazines and other literature. I do not want to get too crazily in-depth, as I do not want to spoil the museum experience. What I will offer, however, is a general overview of what you can expect to see and learn more about should you visit.

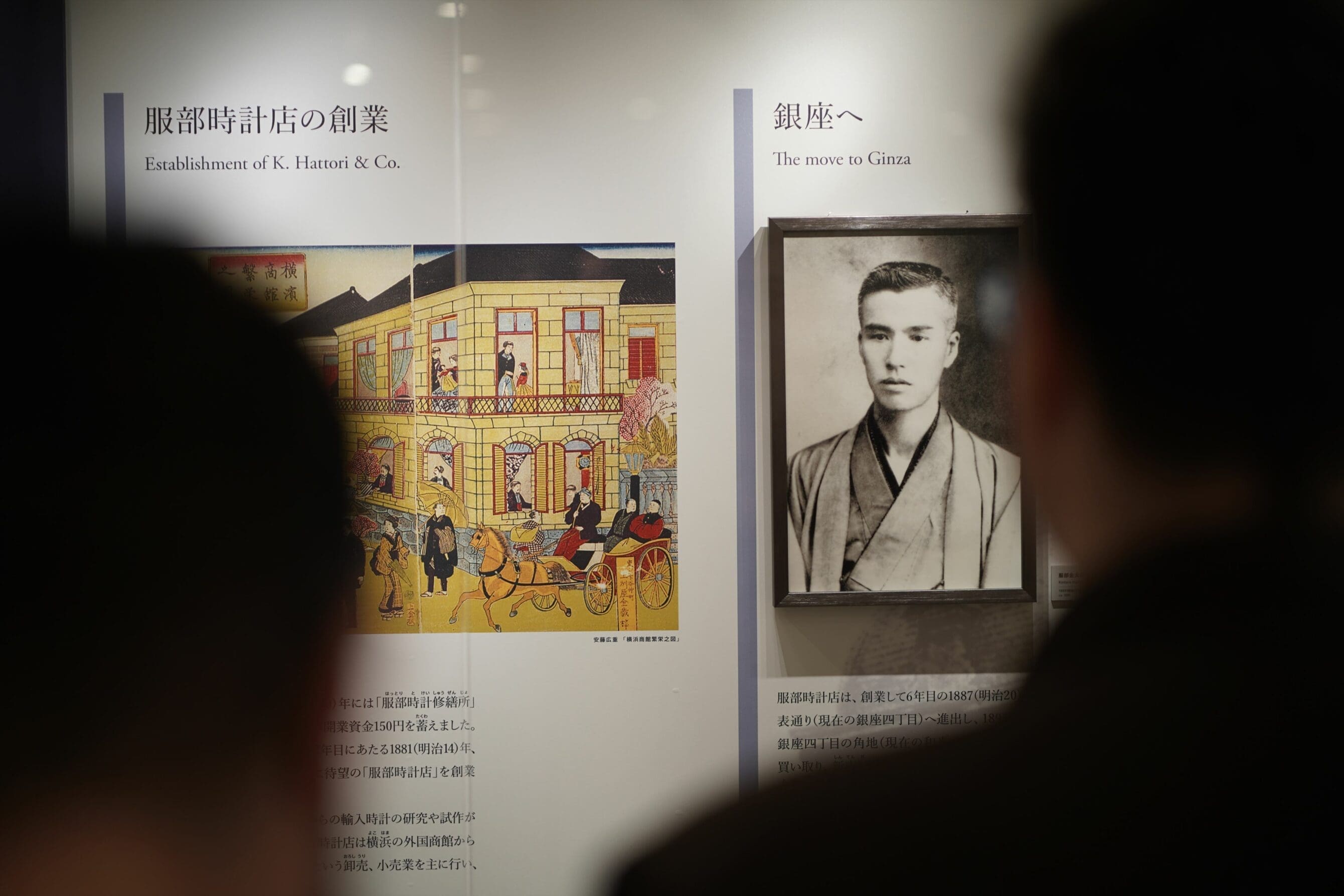

2F: The beginnings of the Seiko Corporation

Seiko is thought of as a giant corporation, but it was not always so. Initially Seiko began as K. Hattori & Co. in 1881 – a shop dedicated to selling and repairing watches and clocks in central Tokyo.

A few years later, Kintaro began to import clocks and pocket watches from other regions. This however was a means to an end. His vision had always been to bring watch manufacturing to Japan, creating Japanese-made watches rather than bringing in pieces from Switzerland and abroad.

This journey towards becoming an in-house vertically integrated manufacture began in 1892 with the opening of the Seikosha factory, and this is when the Seiko name was first introduced. Astoundingly, even as a Seiko-lover I had never realised the origins of the name. In Japanese, Seiko translates to “precision” and Seikosha translates to “the house of precision”. By 1895, the company moved to Ginza and the very building they moved to is now the home of their WAKO flagship, famed Hattori clocktower, and Grand Seiko Atelier Ginza.

While the floor also hosted various machinery and tools used to create Seikosha’s earliest timepieces, the thing that really stood out to me was the integrity of Seiko and Kintaro Hattori after the Great Kanto Earthquake on September 1, 1923. A devastating natural event, the earthquake destroyed various infrastructures within the region including the Seikosha facility and the timepieces within. Just a few months after the disaster, Seikosha placed an ad in the local newspaper proclaiming that any orders destroyed in the earthquake would be honoured and replaced free of charge – maintaining the trust of their consumers. Internally, Hattori also showed his loyalty to his staff by retaining the majority of his staff during the rebuilding of his facilities and continued to pay them even though they were unable to return to work.

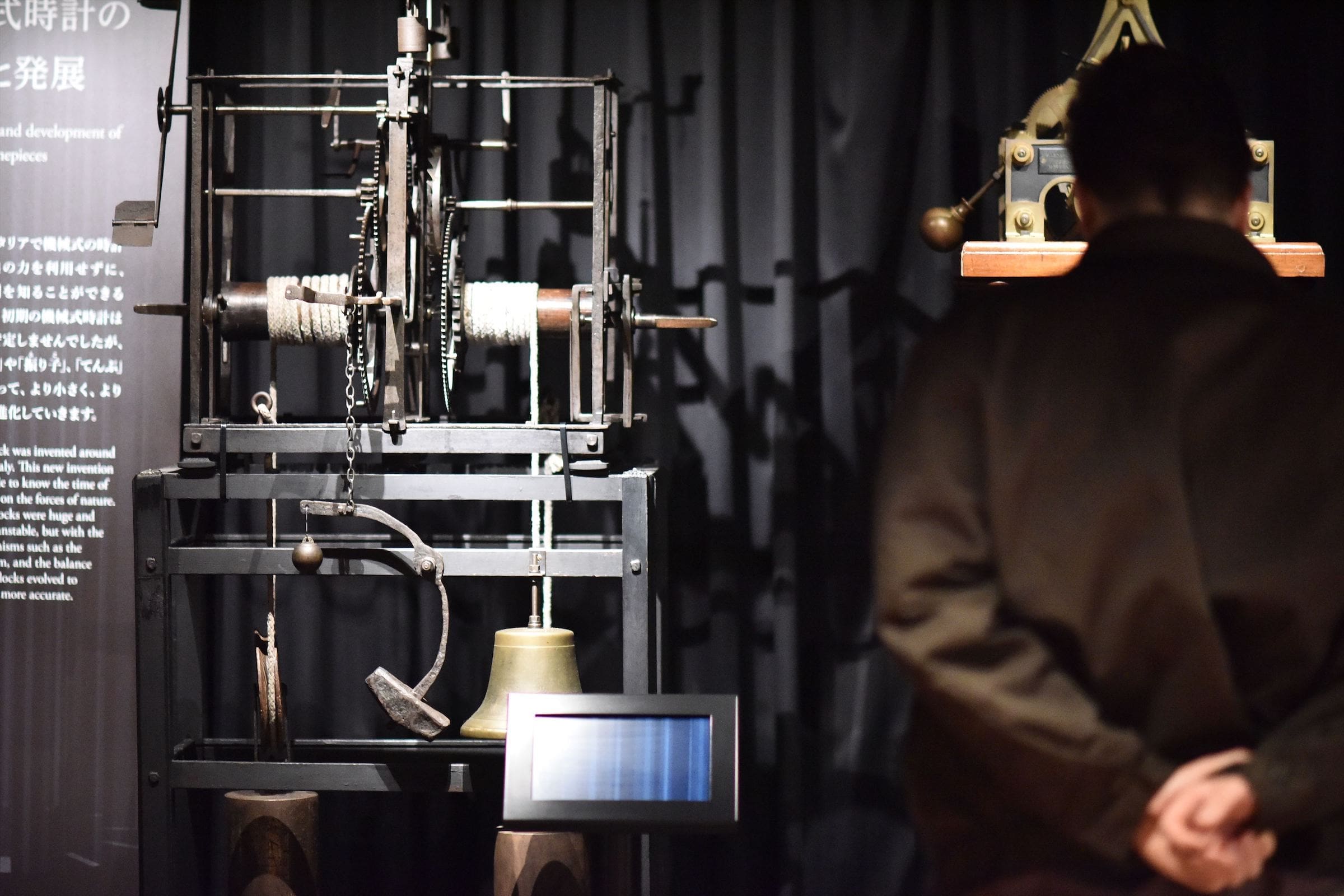

3F: The beginnings of telling time – through nature and devices

In order to best prepare their visitors for understanding their pursuit of precision, and high quality Japanese watchmaking, the Seiko Museum Ginza dedicates an entire floor to the history of timekeeping. The museum explains that the measurement of time can be traced all the way back 7,000 years ago in Ancient Egypt. As a house of precision, the floor has effectively curated devices that convey not only how time was measured over the years, but also the level of precision possible in these times. Today, the Grand Seiko standard is within +5/-3 seconds per day for their mechanical watches. Long ago, however, the most precise timekeeping devices had deviations of hours per day.

Initially, the measurement of time heavily relied on nature – which, in a way, ties into the “nature of time” motto of Grand Seiko. Various examples of sun dials, water clocks, hourglasses, and combustion clocks were available to see on display. They are beautiful devices, but they also reveal just how good we have it today with our timekeeping devices. We then shift towards examples of early mechanical clocks, with an iron-framed tower clock, pendulum tower clock, lantern clock, and various Wadokei clocks to showcase Japanese craft. The floor does a wonderful job of introducing visitors to the earliest stages of timekeeping, as well as contextualising the significance of the advances Seiko has made within timekeeping.

4F: Seiko’s signature products and pursuit of precision

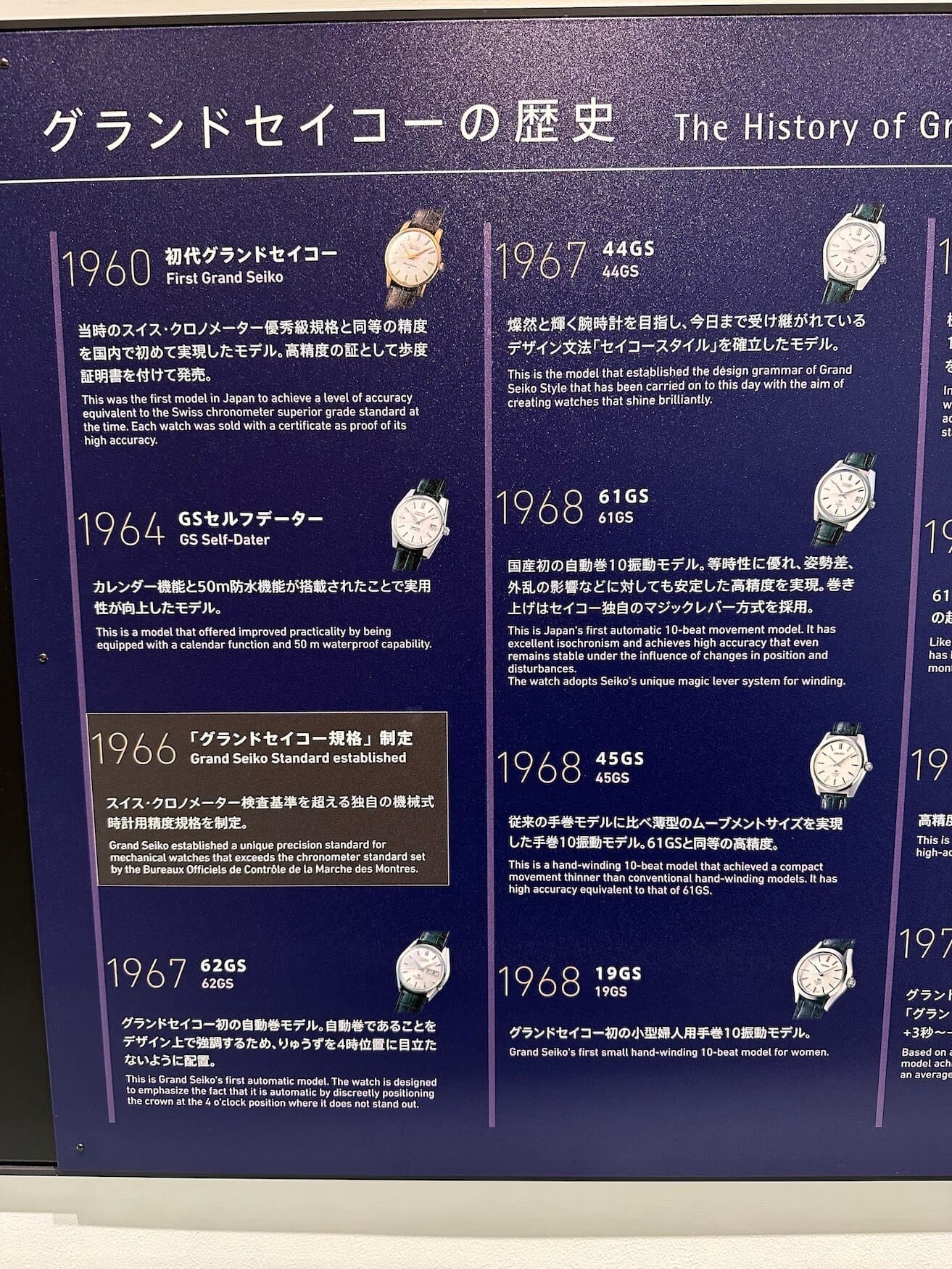

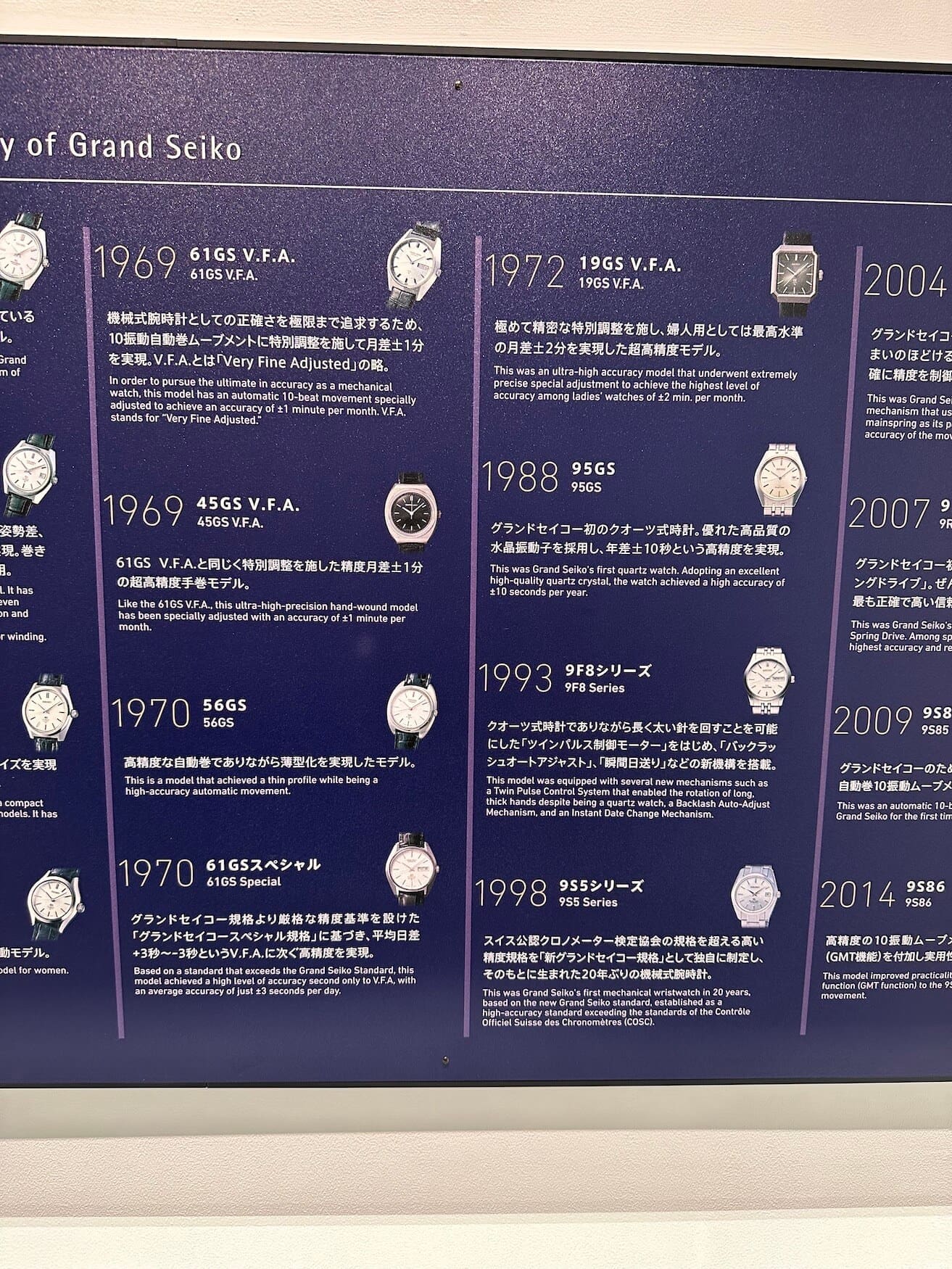

This brings us to the fourth floor, which effectively conveys the strides Seiko has made within the realm of precision.

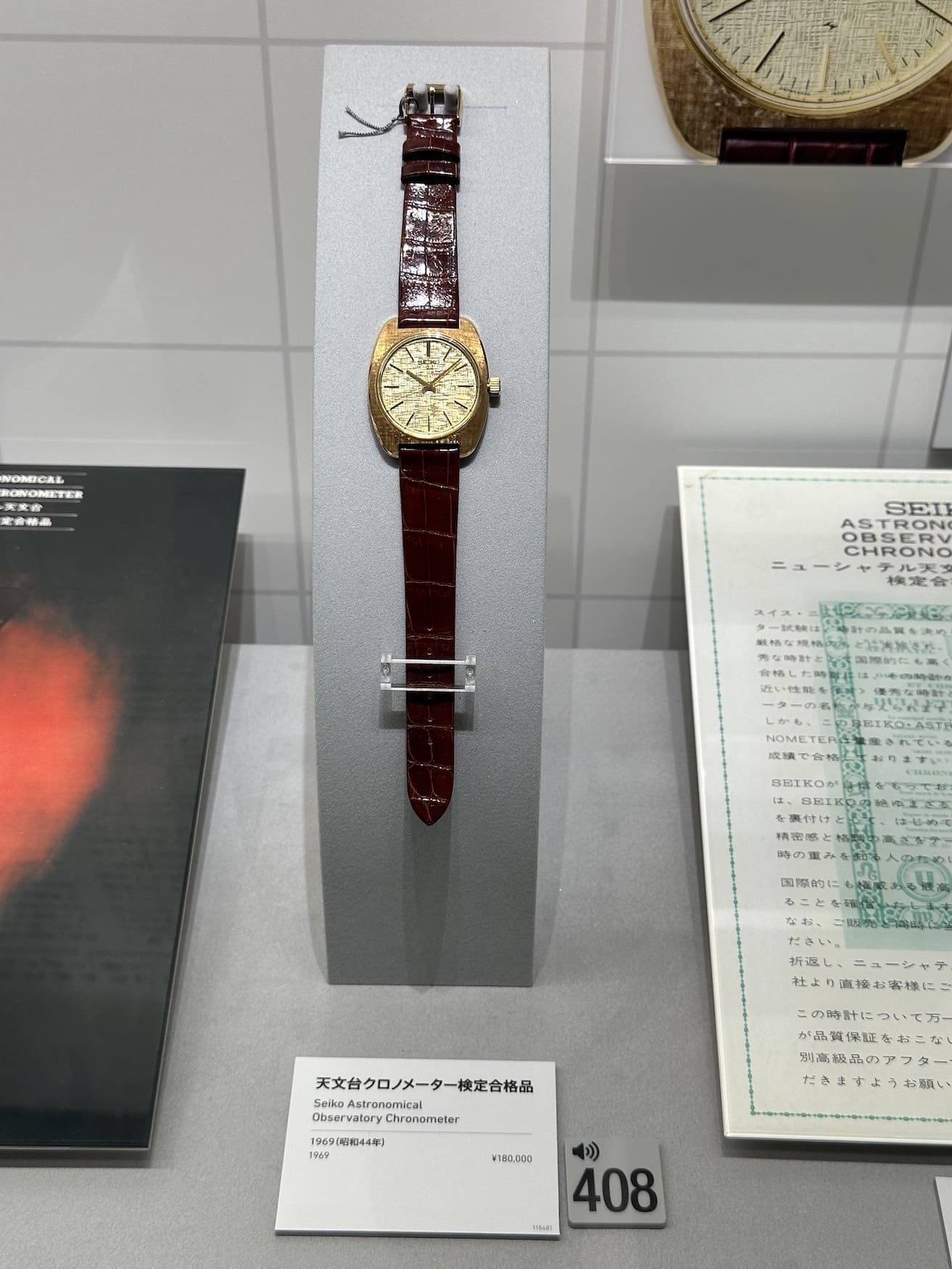

Through the display of some of their earliest signature products, to later timepieces, this floor walks visitors through items ranging from early clocks and wall clocks, to the introduction of Seiko Marvel in 1956, and the launch of Grand Seiko in 1960 and King Seiko in 1961.

Then the pursuit towards ultimate precision in timekeeping is further charted with the observatory competition challenges in Switzerland and Seiko’s journey to winning first prize which began in 1964. Exhibits also chart the birth of the first quartz-driven wristwatch in 1969, and, in the same year, the Seiko 5 Sports Speedtimer which became the world’s first self-winding chronograph with a vertical clutch system and column wheel.

Astoundingly, this was only the beginning. There were even more watches on display on the next floor.

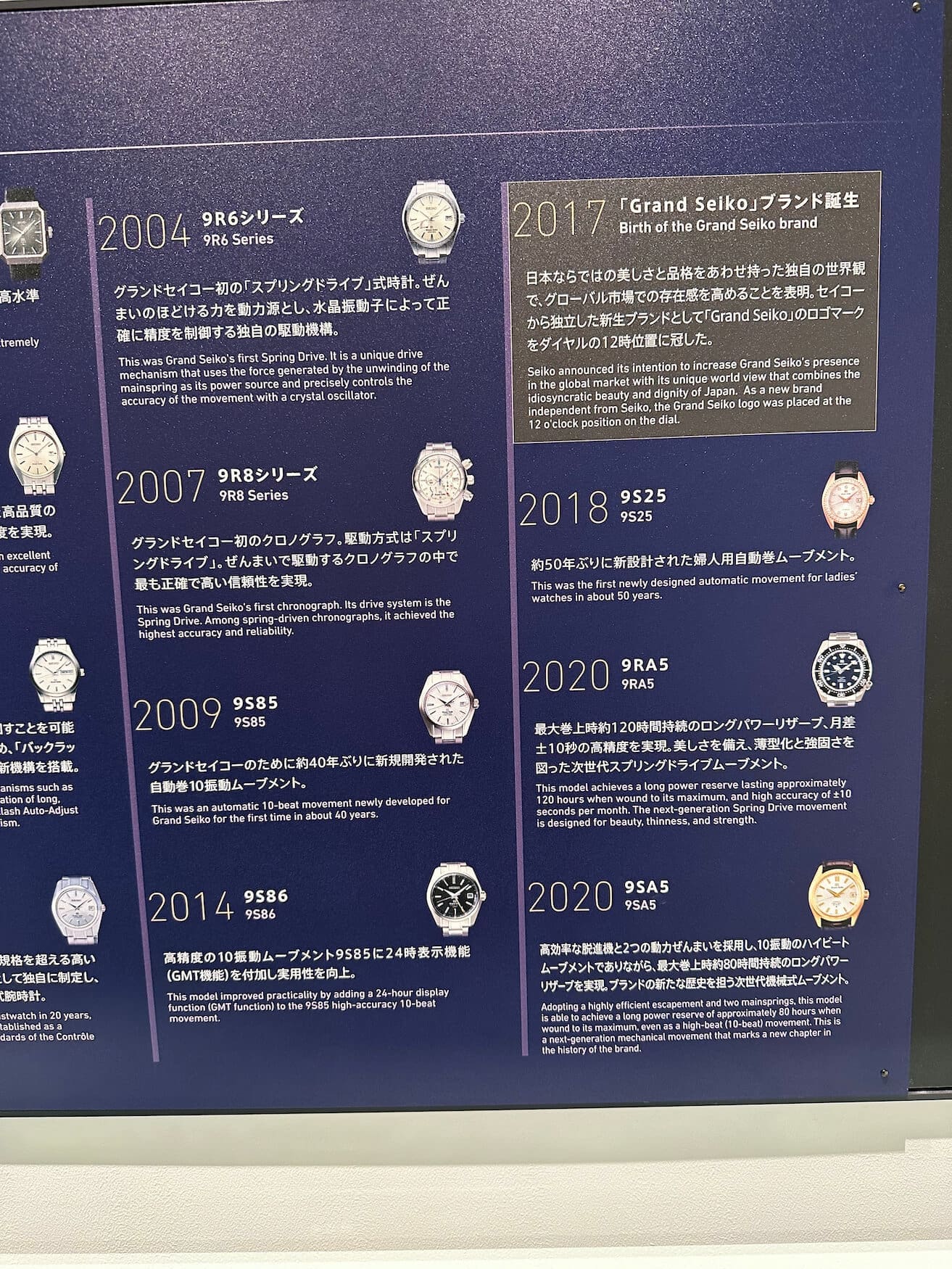

5F: Seiko watches launched since the development of quartz

If your goal is to see every iconic Seiko reference ever made “in the metal”, then the fourth floor is certainly where you start. But, the fifth floor hosts all of the creations post the development of quartz in 1969. This floor aims to convey the “variety of times” of the Seiko brand post 1969: “Unceasing time” represented by their watches without the need for battery changes, “Accurate time anywhere” represented by their watches with GPS and other forms of radio wave correction, “Beautiful time” represented by the high-end creations of their very talented craftspeople, “Quality time” represented by a wide array of Grand Seiko watches also seen on the timeline above, “Fun time” represented by watches incorporating sound and motion (beyond the typical means), and even “Fashion time” representing collaborations with popular culture and other timepieces that celebrate fashion.

The ’80s era of Seiko is fascinating to take in, for example the TV Watch from 1982 that made a cool gadgetry cameo in 1983 007 film Octopussy. Prop watches in such films have to be modified to display the cool high-tech gadgets within. The Seiko TV Watch, however, was emblematic of how high-tech and futuristic the watch was, as it innately fulfilled the requirements of being a Bond gadget.

A proud moment for me was seeing one of the 500 SBWA001 watches inside of a glass case, a watch I am proud to own and have detailed my hunt for – the first story I ever wrote for Time+Tide. This watch first, released in 1999, marked the first-ever Seiko Spring Drive commercial release.

There are also opportunities to see very high-end creations from Credor and the Micro Artist Studio as well. Look, I could detail every important reference you can see here. But, as I mentioned earlier, the museum presides over 10,000+ watches. Being in the museum, and quite frankly during the trip overall, I wished that Marcus was with me to film these experiences. Who knows… maybe some day.

B1: Extreme timing: Olympics, outer space, and more

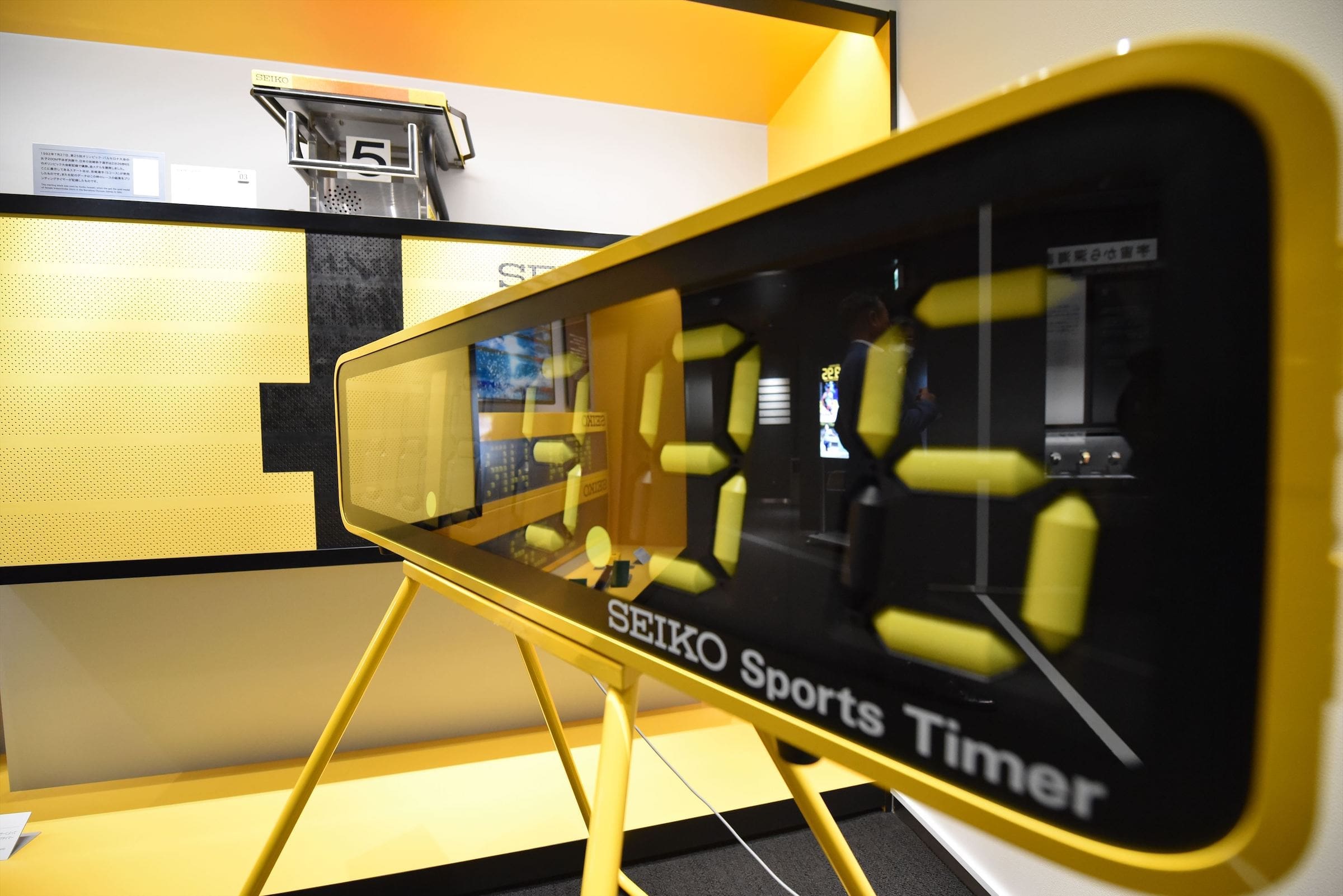

We then made our way down to the basement, and here you can see Seiko’s involvement in the world of sports and extreme timekeeping. Everything from their instruments used in outer space, to the deep sea, to the Olympics can be viewed on this floor.

Various timekeepers, like the above Seiko Sports Timer, used during the Olympic Games were on display. What event better encapsulates, or displays the need for, precision timekeeping.

They were able to develop mechanical stopwatches that could track times to 1/10th of a second as early as 1964, and would develop timekeepers tailor made for specific sports such as football, basketball, rowing, swimming and more.

Various watches also showed their ability to keep time in extreme conditions, such as the Seiko 62MAS (Japan’s first dive watch from 1965) marking the beginning of their deep sea watches to the Seiko “Spacewalk” which went to outer space. The “Spacewalk” I find particularly fascinating, as I would argue it was the most accurate analog wristwatch ever used in outer space. It is Seiko Spring Drive, and therefore presents far greater accuracy than any other wound watch to also make the journey. These watches are rather rare today, and go for a lot of money on the secondary market.

Clearly, this run through is just a taste of all the Seiko Museum Ginza has to offer. A mere fraction. There is plenty more to learn and see, and any Seiko fan who finds themselves in Japan or Ginza must make a stop at the museum in order to keep their Seiko-geek badge. On a more serious note, the museum really is a space where you can get the most intimate look at the history of the brand. And, as you walk through each floor, you begin to understand just how vast and rich Seiko’s history really is. Being the first to produce Japanese-made wristwatches meant bringing all the traditional skills of watchmaking to the region. Adding on top of that the goal of ultimate precision, you then have the journey of not only creating some of the best mechanical timekeepers, but also the new means of keeping time in a manner far accurate than ever before – inadvertently creating the quartz crisis. Seiko is a powerhouse of precision, and to fully digest its evolution you have to visit this museum – it is well worth the trip.