OPINION: Forget men and women, watches don’t need genders

Sandra LaneDo we ever see adverts calling an Audi A3 a “ladies’ car”, a Porsche 911 or Toyota LandCruiser a “men’s car”? Nope. So, when even the notoriously non-PC motor industry refrains from classifying cars in mutually exclusive gender terms, why does the watch industry persist in doing so?

Now, men and women are clearly different. But in terms of style, taste and habits, the traits of masculinity and femininity exist on a spectrum; there’s no fixed divide. So, in an age when nobody bats an eyelid at men wearing pink or women wearing trousers – well, apart from a handful of airline CEOs who still insist that the “hostesses” wear skirts – the rigid classification of watches as men’s and women’s (or the old-fashioned and rather patronising “ladies”) is an anachronism.

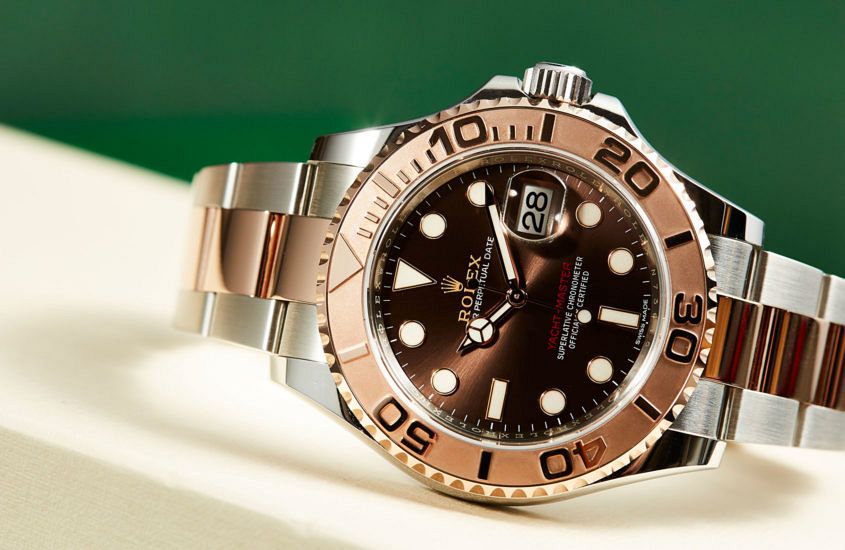

Of course, at the poles of this spectrum, there are watches that exude traditional, typecast masculinity (huge, aggressively butch tool watches) and femininity (delicate, gem-set dress watches), and there’s no reason for the best examples of each genre to compromise. However, in the vast middle between these extremes, there’s no need for gender labels.

Why shouldn’t a man wear a modestly sized or gem-set watch? (Let’s remember that until the 20th century, men were the peacocks – grammatically they couldn’t have been peahens but that’s not my point – happy to smother themselves in gemstones, lace and brocade.) The thing is, he almost certainly won’t choose a watch if it’s in the “womens” section of the catalogue. And why shouldn’t a woman wear a large, unadorned, utilitarian timepiece – so long as it fits her wrist? (As it happens, women are inclined to overlook a “men’s” label if they like the watch.)

Androgynous designs have existed for more than a century: Cartier’s Tank (introduced in 1917), Jaeger-LeCoultre’s Reverso (1931); the Bulgari-Bulgari (originally Bulgari-Roma, mid-1970s); AP’s Royal Oak; Patek’s Aquanaut and Nautilus – all are worn in roughly equal numbers by men and women. Nobody would ever think a man less masculine for wearing a Rolex Datejust, a woman less feminine for wearing a Day-Date, or vice versa. In 2000, Jacques Helleu designed Chanel’s J12 for himself and, although it has been heavily adopted by women, there’s nothing “un-masculine” about it. Reading these examples, have you noticed that they all belong to that rarefied category of designs that can properly be termed icons?

They are exceptional, too, in the sense that watchmaking on the whole became increasingly polarised during the 20th century – ironically, just as gender lines became increasingly blurred in everything from professional roles to clothing styles.

The division became even more marked as the renaissance of mechanical watchmaking in the 1990s focused the attention (and the best watches) on men – apparently thanks to the patronising notion among certain men at the top of the industry that women “aren’t interested” in mechanical watches. (Those exact words have been said to me by more than one CEO over the years.) Laydeez watches (thanks, David Brent) were pushed ever further into the wasteland of “shrink it, pink it – and bung in a quartz movement”. (But, lest I digress into one of my favourite soapbox topics, let’s leave it there. I will come back to that particular subject another time.)

The point, I believe, is this: the industry’s artificially rigid gender categorisation is leaving a lot of watch enthusiasts out in the cold. What of men with slimmer wrists? And men whose taste leans towards more classical notions of elegance? And what of women whose style exudes a calm and intelligent confidence, rather than flowers-and-frills fluffiness?

Where are those watches that both men and women can wear – with no compromise to their masculinity or femininity? Watches that exude a confidence and sophistication that doesn’t have to shout to be heard. Properly ‘neutral’ watches that blur the boundaries technically as well as aesthetically.

Some of the more enlightened brands have begun addressing this in the past few years. But there’s a long way to go. In these challenging times, when the watch industry is scrambling for new ways to build its appeal, here is a business opportunity that designers and makers may be missing.