INSIGHT: Exploring Chanel’s watchmaking – the movements

Sandra LaneIt’s seven years since Chanel Horlogerie decided to start developing its own movements in-house and in the last three of those years it has launched three new calibres – or four, when counting Calibre 2.1 separately. Each is strikingly different from anything offered by other haute horlogerie brands – and all are noticeably different from each other.

That’s due to Chanel’s singular approach to watchmaking, which does not follow the usual path of “making engines to then put into various cases”, says Nicolas Beau, the global head of watchmaking and fine jewellery.

“We think of a collection or model at the same time as we think of a calibre because there is a very strong intimacy between the two. It’s one calibre per model. So the first thing we do is imagine a calibre that has the capacity to evolve. And that creates another difficulty, which is that we must try to envision how we want a model to evolve, and in which direction the movements can evolve for it – not just technically but aesthetically as well.”

That’s because, in Chanel’s way of thinking, the aesthetic side is the leader and decision-maker. The creative team first draws the movement, then asks the technicians to make it happen. It’s the antithesis of the traditional approach, where the technical teams make a movement then give it to the designer and say, “there’s the engine; now put it in a case and try to make it look good”.

Although Beau says that there’s no predetermined timing for the release of a new calibre – “when something is ready, it’s ready” – the three core movements released so far look like a remarkably well planned sequence when we see them lined up side by side.

Beau walks us through them, in chronological order.

Calibre 1

“Remember how I said one calibre per watch?” he asks, picking up Calibre 1. “Would you put this in another watch? No. It is really designed for Monsieur. You cannot imagine this in a J12 because it was created for Monsieur, respecting the spirit of Monsieur. You’ll never see it in another collection.”

Despite the brand’s feminine image, Chanel decided to do its first calibre for a men’s watch because the movement world is so masculine-driven, says Beau. “In our way of thinking, men are attracted by the technical aspect, seeing components is something that they value. So we designed the first movement to give maximum attention and beauty to the components – this is our vision of a men’s movement.”

That translates into thin, circular bridges that obscure as little as possible of the functioning parts of the movement – and is why Chanel put so much time and effort into designing the wheels. “The good thing when you start [making movements] from zero is that you don’t have a stock of wheels that you need to use – you can design them exactly as you like,” Beau jokes.

“The strongly three-dimensional architecture of the movement is emphasised by different tones of black, according to whether the finish is satin, matt, circular-grained,” he points out. “It was an opportunity to maximise light reflection so that you see the components really well.”

Calibre 2

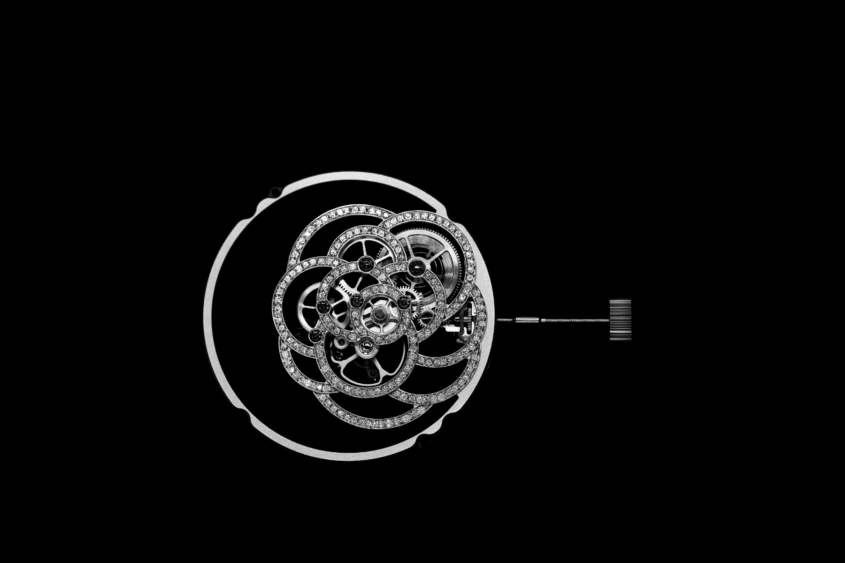

Next up is Calibre 2, which was developed for the Première case (and released in 2017 as the Première Camélia Squelette). “Among ourselves, we refer to Calibre 1 as Mars; this second movement we call Venus,” says Beau.

For its largely female clientele, Chanel wanted to revisit the vision that had been expressed with the Flying Tourbillon developed by APRP [Renaud et Papi] and launched in 2012. It used a tourbillon not only for precision but because it enabled them to have a camellia flower rotating over the dial.

“That watch won the GPHG and has been extremely successful with customers, so it confirmed our idea that women might be interested in mechanical movements – not necessarily for the technical aspect first; more as part of the overall beauty of the piece.”

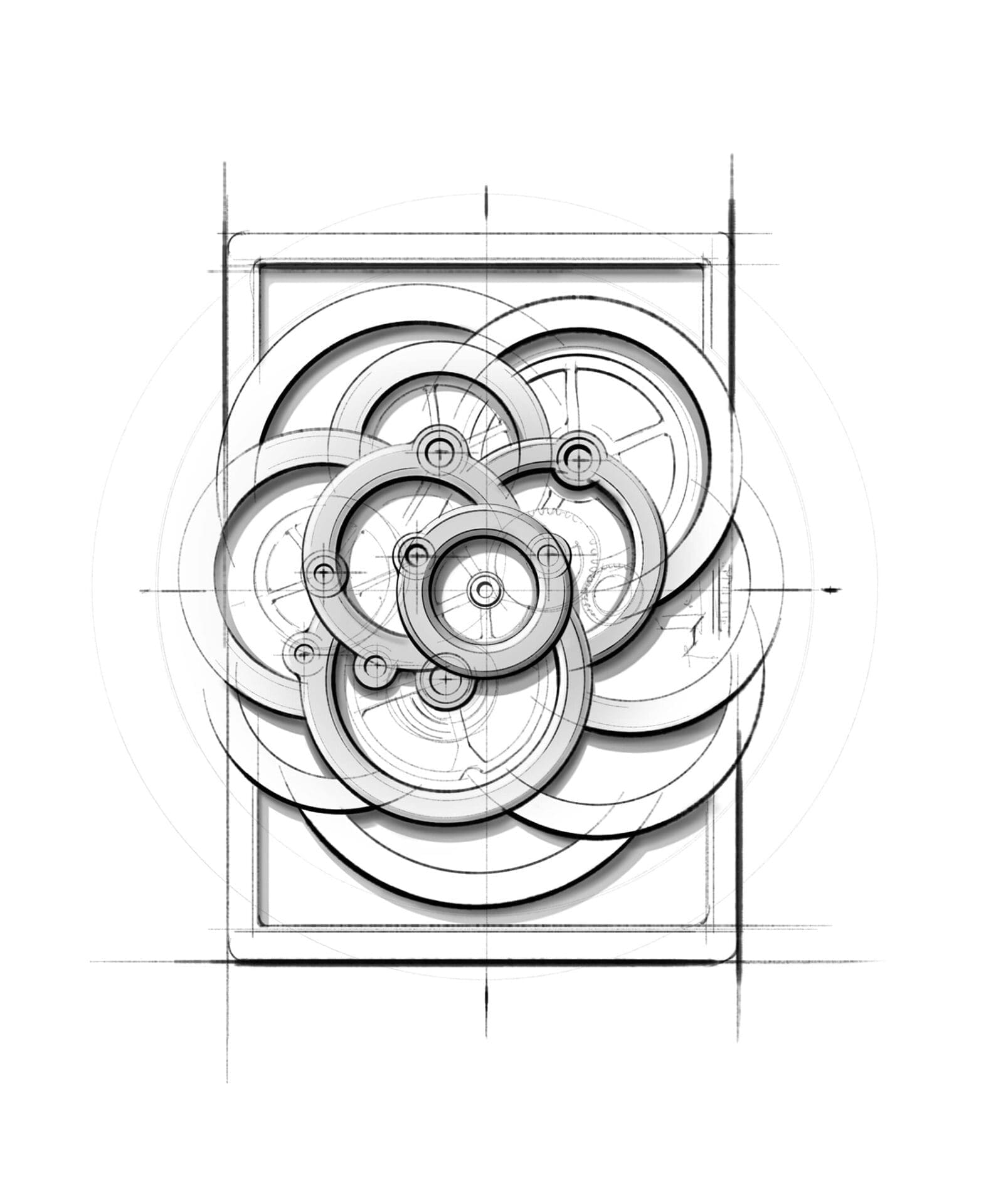

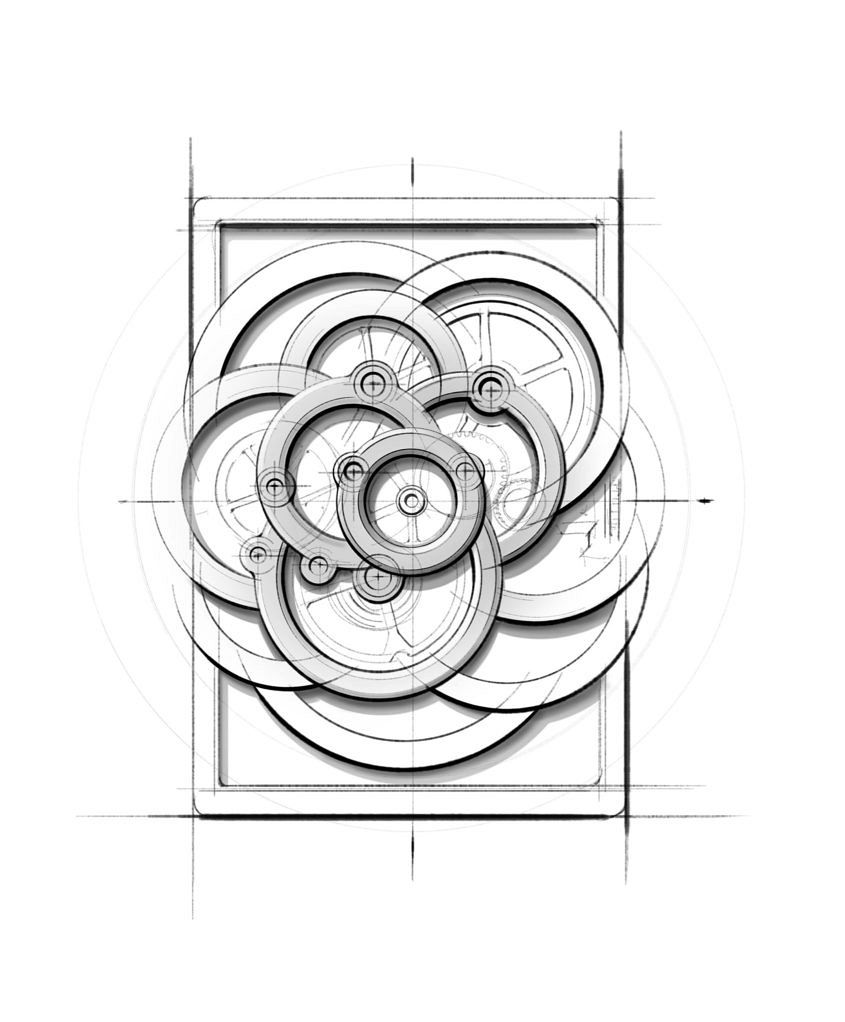

With that in mind, Chanel opted for a skeleton movement – designing the bridges first, as a flower (as opposed to skeletonising, in which metal is removed from the plates of a conventional movement to expose some of its parts), then asking the technical team to develop a movement architecture that would position the wheels within the circular bridges (or “petals”) and to design the wheels to be the same diameter as the circles.

“As a result, you almost don’t see the components at first; you see the flower. Maybe some women really like the mechanical elements – but it is a beautiful object first. It’s another approach.”

Calibre 3

Moving on to Calibre 3 and the Boy.Friend Squelette, Beau reiterates: First, we made the components visible, then we made the components invisible, and in this third approach we do a bit of both.

“We wanted to take some masculine watchmaking attributes and put them into a watch for women. We looked at what Gabrielle Chanel did with jumpers and tweed – taking them from men’s wardrobes to make things for women. And we asked ourselves: How can we express that spirit in a movement?”

The Boy.Friend case already has some masculine attributes – the rectangular shape, the simple buckle, the leather strap. “In essence, it could be a man’s watch, but without any indicators or numerals, it’s not an instrument, which is what I think men do appreciate.”

To add a more masculine element, the design began with the skeleton bridges that would expose the functioning parts. The next task was to make the components neither hidden, like Calibre 2, nor too visible, which would go back to Calibre 1.

“The trick was to make the wheels of full material rather than in the usual style, with arms, and this, I discovered, is something that watchmakers hate because the wheels are heavier and stiffer and so virtually impossible to adjust during assembly.”

To make the wheels they used a galvanic growth technique – growing layers of metal, which ensures that the wheels are absolutely flat, guarantees the exact thickness, and optimises the weight. This was possible thanks to Chanel’s partnership with Romain Gauthier (in whose company it holds a stake), who is able to make them exactly as Chanel wants them to be, says Beau.

The result is a movement that Beau describes as “a bit more Monsieur-type” without being overly masculine. “We played with some other tiny things – such as the colour of the wheels so they are just a little less obvious. The fact that there are no indices and no visible stitching on the strap tip the Boy.Friend onto the feminine side; if we were to add numbers and stitches it would become instantly masculine.”

Calibre 2.1

Seeing the three movements together, it was easy to understand how Chanel develops a watch line and movement line together. But then came an exception to the rule: an adaptation of Calibre 2 from the rectangular case of Première to the round case of Mademoiselle Privé.

“We took Calibre 2 and developed Calibre 2.1 rather than creating Calibre 4 from scratch because it’s essentially the same movement – a floral skeleton – with the architecture reworked into a circular form,” Beau explains.

The Mademoiselle Privé collection is artistic: we have done embroidery, enamel, marquetry, glyptic and gem-setting within this collection and we believe that horology is also a métier d’art. So we thought, why not do one with the skeleton dial, which expresses the métiers d’art through horology. With this movement, the watch is totally in the spirit of the collection.”

Beau readily concedes that Chanel’s design-first approach poses challenges to the technical developers. “I think it may be harder to develop Chanel movement than a regular complication,” he says. “But [technical haute horlogerie] remains a small part of our business – we don’t plan to become another Patek Philippe for women.” Be that as it may, it’s evident from seeing just these four movements that Chanel already has the foundation of a real collection of calibres.