10 important firsts in watchmaking

Fergus NashThe history of watchmaking is an absolutely huge topic, and watch brands will do whatever they can to stand out from the crowd. Aside from just being incredibly popular or being involved in a legendary event, something companies can do is to be the first at something. Whether it’s something obscure like the first colour-changing sapphire case, or significant like the first double-faced watch, those records have a way of sticking around. Although many of the important firsts are contested or riddled with conditions, let’s run through some of the firsts in watchmaking that are still relevant to us.

The first modern wristwatch

After Louis Cartier made a watch for the early pilot Alberto Santos-Dumont in 1904, it finally reached the Parisian public in 1911. Before then, the only function-driven wristwatches were the ‘wristlets’ occasionally worn by soldiers and military officers in the late 1800s. There were also jewellery-oriented wristwatches marketed towards women, including one made by Breguet for the Queen of Naples in 1810. With a movement produced by Edmond Jaeger and Jacques-David LeCoultre, later founders of Jaeger-Lecoultre, the Cartier Santos-Dumont was the first mass-produced wristwatch not specifically made to be an object of beauty or military purpose. That’s what marks it as the beginning of contemporary wristwatches as we currently think of them. It subsequently also claims the title of being the first pilot’s watch.

The first automatic wristwatch

Although automatic movements had been made for pocket watches towards the end of the 18th century, they weren’t really practical enough to take off. It wasn’t until watches landed on the wrist that they were moved around enough to generate adequate power, and it was the English watchmaker John Harwood who made it happen. He filed and received his patent in 1923, and the technology would make its way into the Swiss-made Fortis wristwatches later in the decade. The 360-degree winding rotors we’re familiar with today would appear in 1930 in Rolex watches, but Harwood’s ‘bumper’ movement remained fairly popular until the 1950s.

The first chronograph

Up until 2013, it was believed that the first chronograph was invented by Nicolas Mathieu Rieussec in 1823 to time horse races. It came in a large box and would drop ink on the dial to make a mark within one second’s accuracy. It not only turned out that the actual first chronograph came a few years earlier, but that it was far technologically superior. The chronograph completed by Louis Moinet in 1816 is completely recognisable as a stopwatch in the modern sense, with start, stop, and reset functionality. The subdials record seconds, minutes and hours just like a modern chronograph does, but the craziest element is the beat rate. Operating at 216,000 vibrations per hour or a whopping 30Hz, this chronograph was capable of accuracy down to 1/60th of a second. That wouldn’t be bested until Heuer’s Mikrograph 100 years later. Louis Moinet’s work is the definition of being ahead of its time.

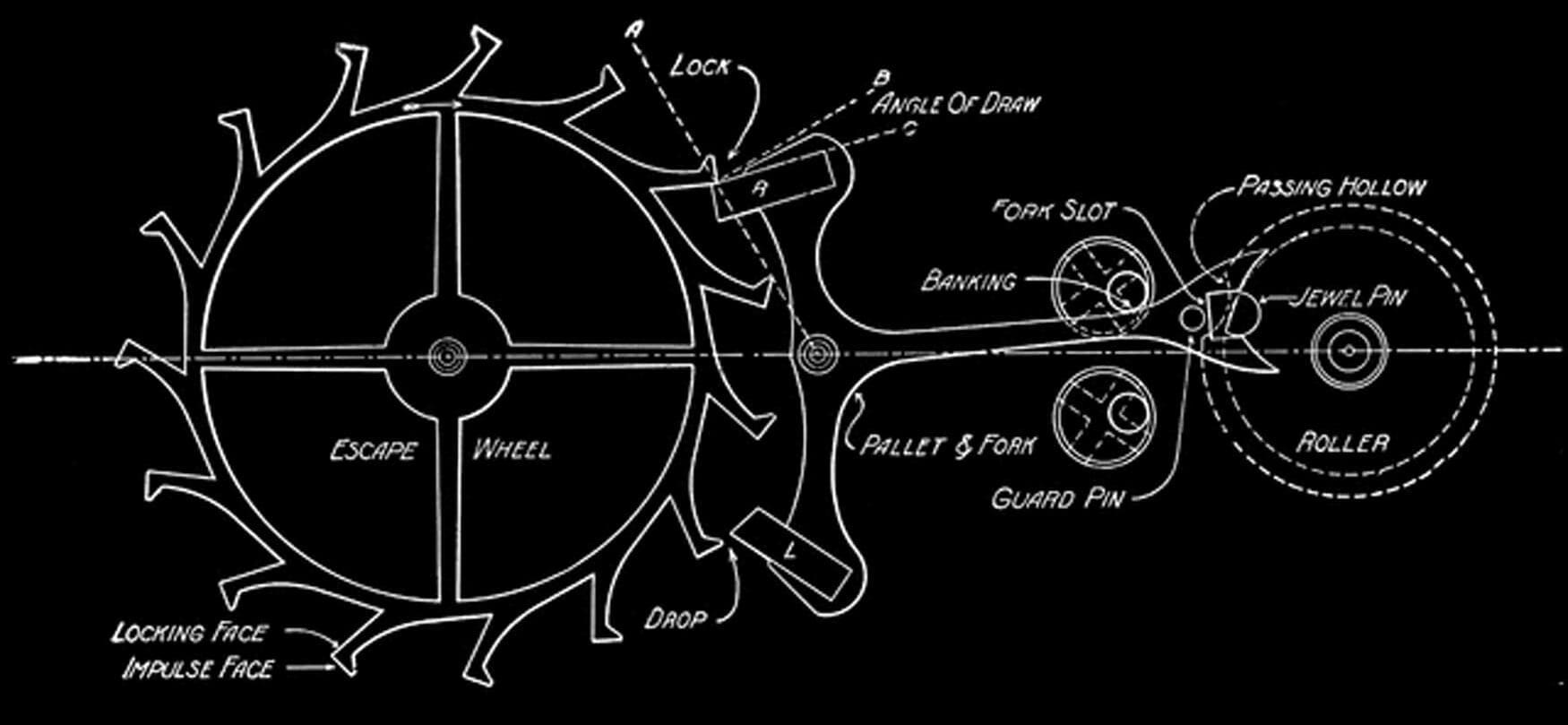

The first lever escapement

There have been plenty of different designs for escapements throughout the history of timekeeping, but Thomas Mudge’s invention of the lever escapement some time around 1775 has proved time and time again to be the best solution for releasing the mainspring’s power in an accurate and reliable way. It’s debated how long it took for Mudge’s design to be built into a watch, and it was improved upon by several watchmakers including Abraham-Louis Breguet in following years, but today it is by far the most common escapement used in mechanical watchmaking.

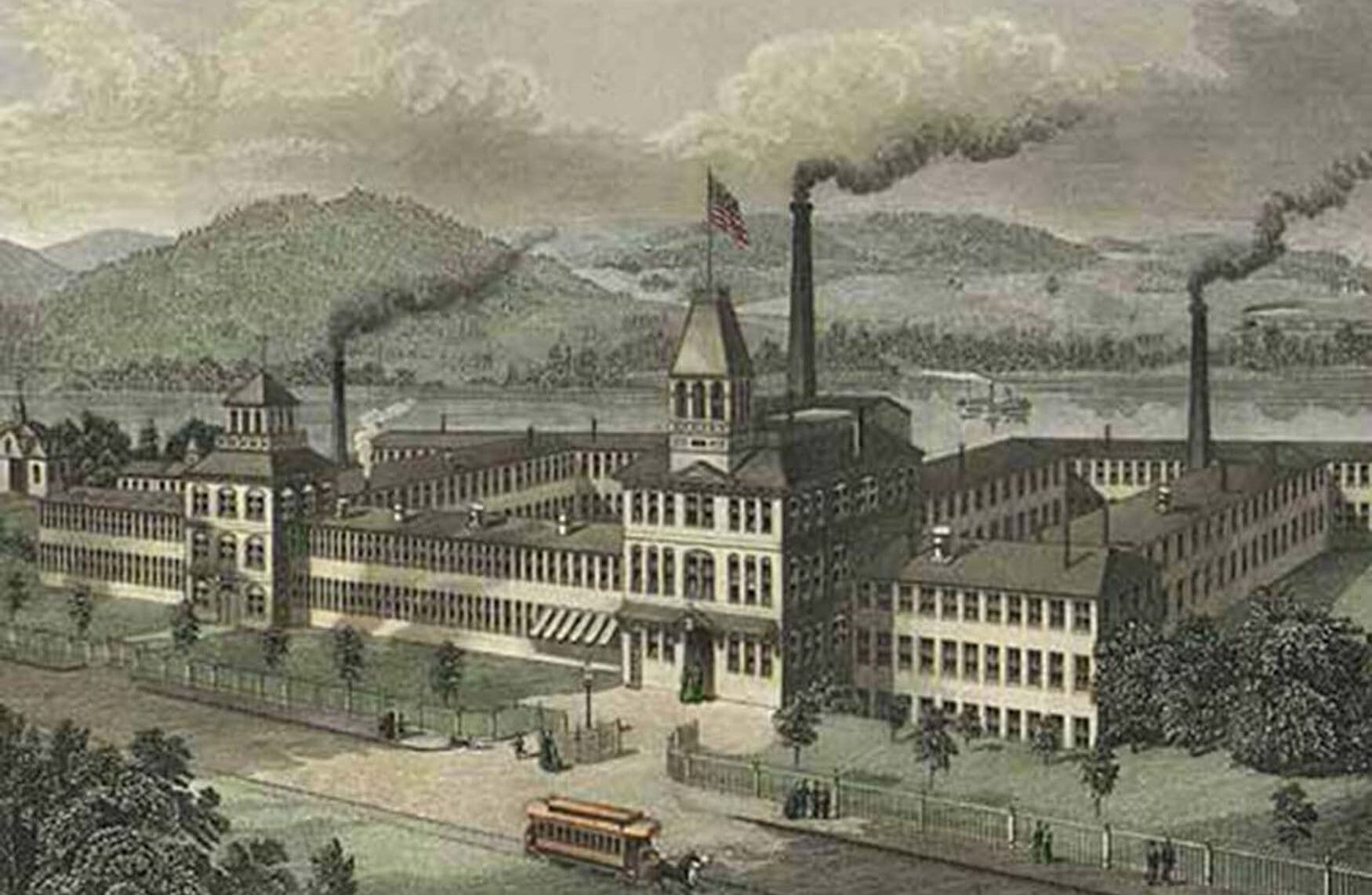

The first American watch factory

The concept of a watch factory was definitely nothing new by the 1850s, however it was American manufacturing methods which led to mass-production, affordable watches, and efficiency that can be seen in every modern watch factory. The first was the Waltham Watch Company, which had some rocky beginnings but hit its boom during the American Civil War. Their success was so astonishing that it threatened the existence of the entire Swiss watch industry, and the Swiss had to adopt American methods throughout the 1870s and ‘80s or risk falling behind. Although Waltham terminated operations as a result of the quartz crisis, the historical factory in Massachusetts still stands as refurbished apartments, offices, and restaurants.

The first cam-actuated chronograph

Bringing chronographs to the masses from 1937 onwards, Landeron created the Landeron 47 and 48 soon after. By eliminating the column wheel and replacing it with a cam switch, movement components didn’t need to be machined as precisely for reliable operation. That meant they were quicker to produce and the cost dropped dramatically, just in time for World War II. Landeron would later go on to produce the first Swiss electric movement in 1961, although that would contribute to their downfall during the quartz crisis.

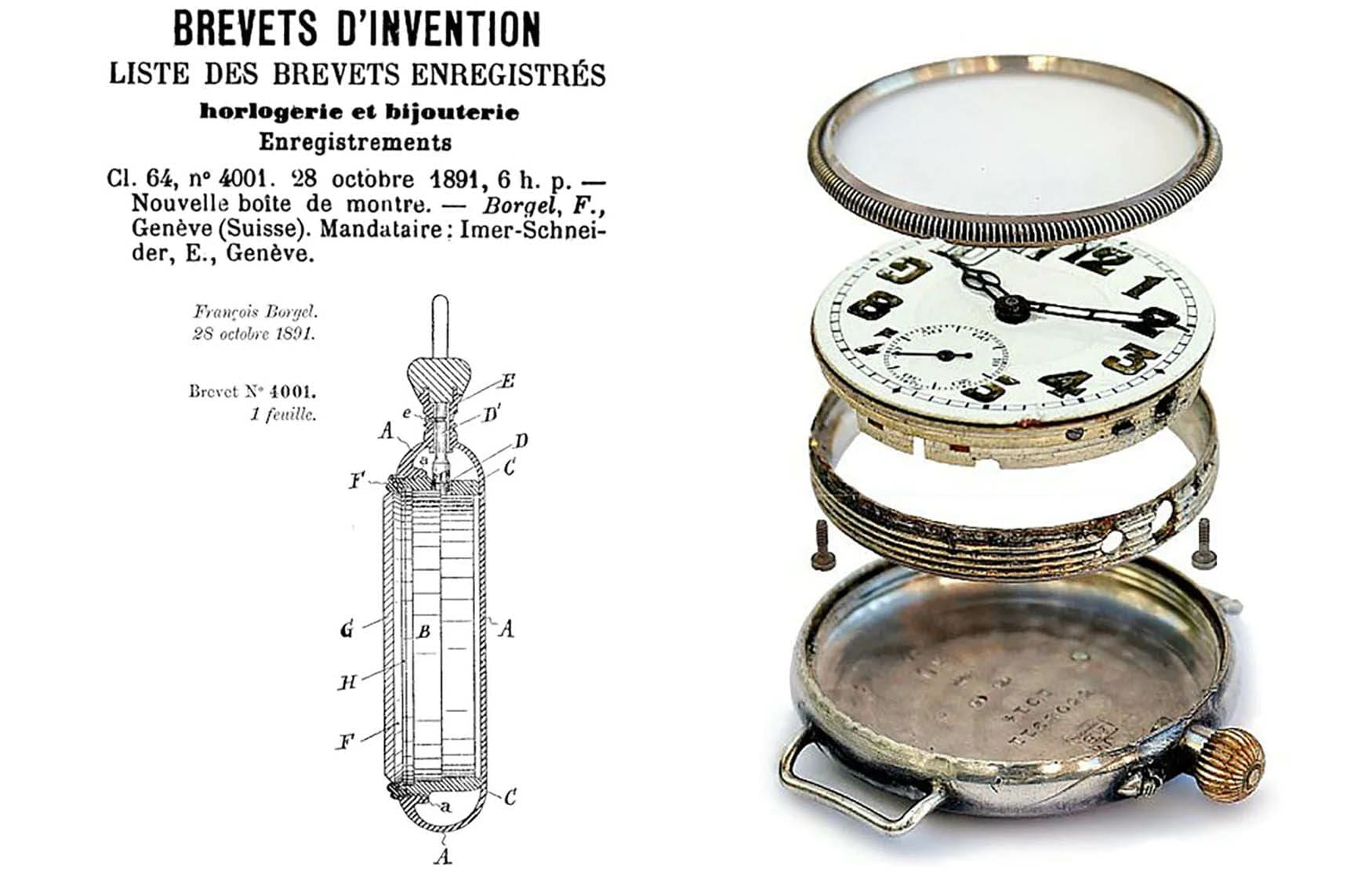

The first waterproof watch case

All watches have some inherent level of water resistance, whether it be next to nothing or capable of diving 6,000m. The debate as to the first-ever dive watch will rage on for eternity between Rolex, Blancpain, Zodiac et al., however when considering the title of ‘waterproof’ alone, there is actually a less contentious contender. Developed in the late 19th century and patented by François Borgel in 1891, what would become known as the ‘Borgel screw case’ provided moisture and dust protection far beyond any of its contemporaries. The watch movement and dial were threaded into a one-piece case, using the bezel to grip it. It became an incredibly popular design with military officers fighting in trenches, and the amount which survive in good condition today prove their effectiveness. To call them ‘impermeable’ as they did was definitely a stretch by modern standards, but it was a key development in the evolution of watches to wristwatches.

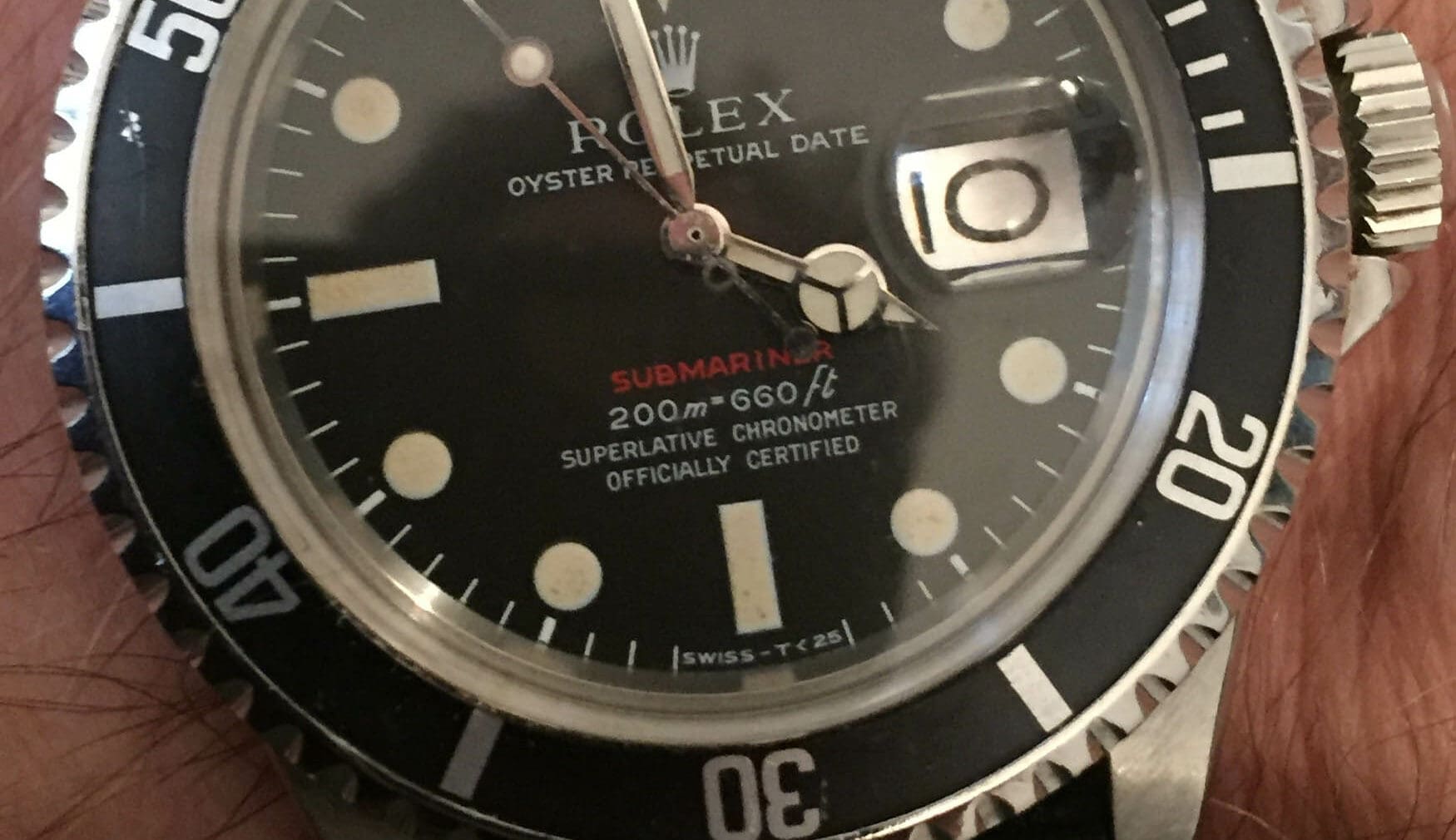

The first non-radioactive lume

The use of radium to make luminous watch dials exploded at the start of WWI, as its tactical advantages were obvious. But at the time, the dangers of radioactivity were largely unknown and radium even found its way into people’s drinks and facial creams for its supposed health benefits. Once the horrors became apparent, an alternative was needed. Radium-Chemie Teufen, later called RC Tritec, was the first company to figure out how to use tritium by stabilising it in a polymer form, and it was approved by the US Nuclear Regulatory Commission in 1962. This allowed luminous dials to evolve freely, and RC Tritec also created Swiss Super-LumiNova in 1996 to further reduce any anxieties about radioactivity and improve brightness.

The first tourbillon

Possibly the best-known inventor on this list is Abraham-Louis Breguet and his patented tourbillon regulator from 1801. Although it would take a fair few years to be presented to the public, this complication is perhaps the most emblematic work of Breguet’s genius. By rotating the entire escapement within a wheel, the effect of gravity which pulled on the weighted balance could be nullified. This eliminated ‘poise errors’ when a watch was facing dial-out, as it would be when sitting inside a coat pocket. The tourbillon is much less effective on wristwatches where the dial-up position is more common, however it’s still considered to be one of the pinnacle complications of mechanical watchmaking.

The first shock-resistance

Yet another one of Abraham-Louis Breguet’s invention predates the tourbillon by a decade, and it’s something which affects pretty much all contemporary watches. The most delicate part of watch movements were the pivot points, as a small shock could snap them and ruin the whole thing. Using conical pivots and spring suspension, Breguet created an anti-shock system in 1790 which he called the para-chute. Today, most mechanical movements use the Incabloc system or a variation invented by Georges Braunschweig and Fritz Marti in 1934.