EDITOR’S PICK: Knowledge, kinship & “celebrity vampirism” – the psychology of why we collect watches

Luke BenedictusEDITOR’S PICK: Last week, the Only Watch 2021 auction racked up the phenomenal result of $32.1 million USD. Admittedly, there’s a charitable motive behind the initiative, but even so, the vast sums of money splurged there on watches by Audemars Piguet, F.P. Journe and alike, suggest that watch collecting is still in a very healthy place. But why are people willing to spend so much on what are, after all, increasingly redundant pieces of technology? We asked a clinical psychologist who specialises in compulsive behaviour to find out.

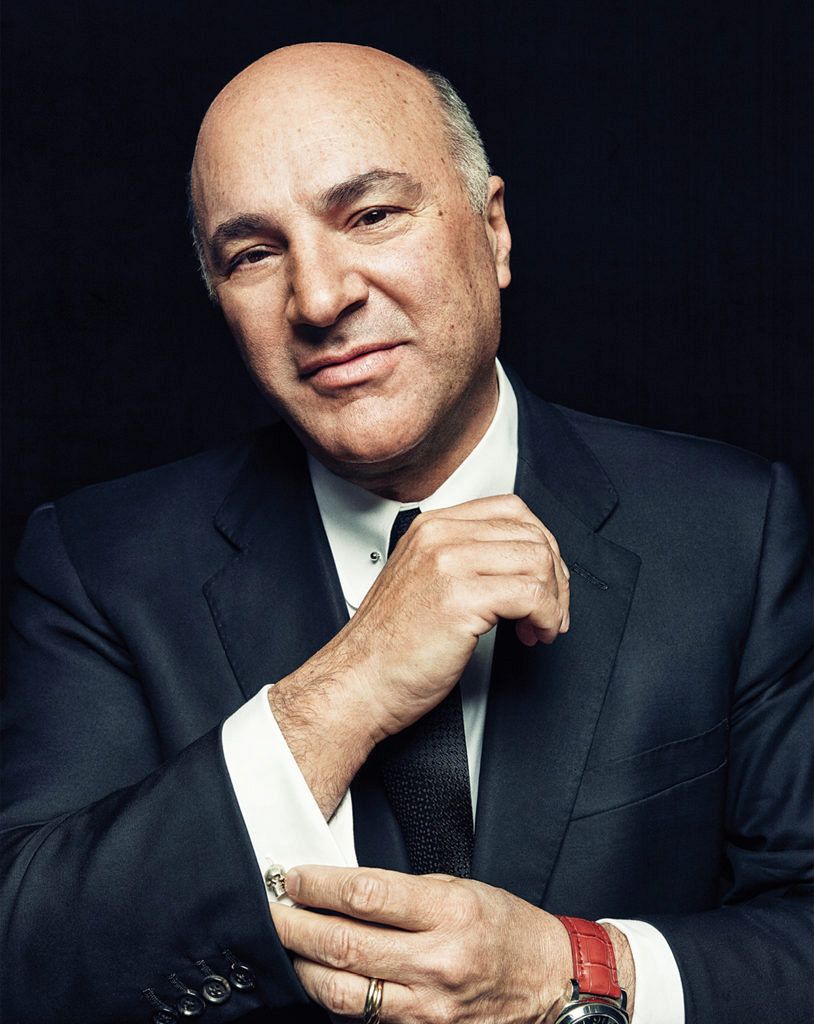

“Completely irrational”, “a horrible affliction”, “the disease” … that’s how Shark Tank investor Kevin O’Leary described his obsession with watch collecting in a Time+Tide interview (read it here).

It’s easy to understand O’Leary’s ambivalence about his hobby. After all, viewed from a certain perspective, watch collecting doesn’t make an awful lot of sense. Watches are not only often wincingly expensive, they’re also functionally redundant in that you can always tell the time by glancing at your phone. The desire to collect multiple watches can therefore seem even more nonsensical. Particularly if you keep most of them stashed in a safe.

So why do we devote so much time, effort and resources to such an illogical pursuit?

Dr Richard Moulding is a clinical psychologist and senior lecturer at Deakin University and specialises in compulsive behaviour. He believes that timepieces are particularly desirable things to collect due to their multi-faceted nature.

“People collect things they’re passionate about and get enjoyment from,” Dr Moulding says. “Watches tick a lot of boxes in terms of collectibles. There’s the technological side in terms of their movements, the different finishes and the advancements in precision. But watches are also aesthetic objects – some look better than others.”

The pursuit of knowledge

Yet collecting watches is about more than the naked acquisition of material objects. “It’s not just about gaining watches,” Dr Moulding says. “It’s gaining knowledge about the watches.”

Anyone with the faintest interest in watches will recognise the truth in this statement. For the timekeeping newbie, the horological universe may seem full of technical mumbo-jumbo and arcane jargon. But once you’re wrist deep, you soon start to know your chronometers from your chronographs, and you cherish those watches that are both. And the more you know, the more your appreciation grows. This sparks a self-perpetuating momentum, driving you deeper down the horological rabbit hole.

To some extent, watches fast-track this initiation process because of the high cost of entry. Before you buy a new timepiece, you want to be damn sure you’ve done some research. As a result, buying a watch is one of the more considered purchases that many people make. You read up on brands, models and movements in order to make an informed decision and avoid buyer’s remorse.

As Dr Moulding explains: “When you learn more about the object you’re collecting, you gain more enjoyment out of it, you gain expertise and you become more knowledgeable.”

The sense of kinship

As people accumulate knowledge, it makes sense that they then want to share it with like-minded folk. “Communities spring up around collecting, whether that’s through forum chatrooms or exchanging knowledge or photos,” Dr Moulding says.

Such transference of information is easier than ever in the digital age. Most of the biggest watch brands – Rolex, Omega, TAG Heuer, Seiko et al. – have online forums in which fellow aficionados share discoveries, compare valuations and discuss whether the rotor on a Datejust 41 is just that little bit too loud.

In his book, Collecting: An Unruly Passion, Dr Werner Muensterberger comments on how collectors often seek validation from similar enthusiasts. The psychoanalyst writes that the “need for authentication and approval by experts is a reflection of two forces existing within the collector: the desire for self-assertion through ownership and a sense of guilt over narcissistic urges and pride”.

This may be overthinking things a touch. But there’s no doubt that most forms of mainstream collecting will produce tribal communities whose common passion offers a form of connection. “Many collectibles don’t have an innate value,” says Dr Moulding. “Their value is recognised by the community.”

A potential financial return

Fortunately, a good watch in reasonable nick from a credible brand has a fair chance of maintaining its financial worth. “As with cars or art, a watch collection will have monetary value,” Dr Moulding says. “That’s not the case with spoons or miniature collectibles.”

Hopefully, the resale price is not the only reason you buy a watch. But there’s no denying this extra incentive may galvanise your interest and prompt you to pursue certain pieces with a little more vigour. (Particularly if it allows you to snaffle up another watch on the justification that it’s “a good investment”…)

The thrill of the chase

In addition, Dr Moulding points out that the scarcity of certain watches and limited-edition releases will only sharpen their desirability. This can add a “thrill of the chase” element to watch collecting. Pursuing a birth-year Submariner or rare vintage piece can sometimes escalate into a genuine quest – they’re not called “grail watches” for nothing.

In that respect, watch collecting can give you a concrete goal to pursue. Given the increasingly haphazard nature of life, such clarity of purpose can offer a reassuring sense of control.

As Dr Muensterberger writes, collecting isn’t psychologically unhealthy if kept within reasonable bounds. “It is a device to tolerate frustration and a way of converting a sense of passive irritation, if not anger, into challenge and accomplishment.”

Celebrity vampirism

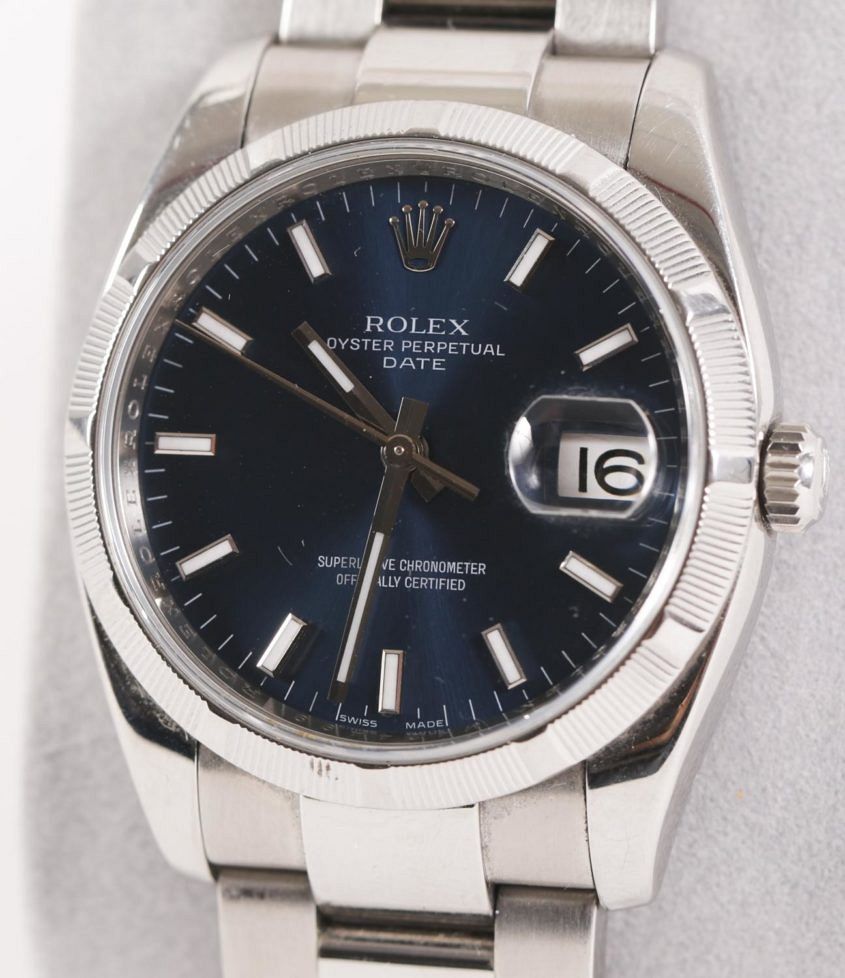

Last year, an assortment of watches belonging to the late TV presenter and chef Anthony Bourdain went up for auction. The final bids massively exceeded the expectations. The posted estimate for Bourdain’s stainless steel Rolex Oyster Perpetual Date was US$2000 to $4000. The eventual price: US$48,750. In addition, Bourdain’s Panerai Radiomir went for $33,750 and his TAG Heuer Monaco for $20,627.

This is hardly an isolated example. Watches belonging to the late and great often command incredible prices. Marlon Brando’s Rolex GMT-Master fetched US$1.6 million at auction while Paul Newman’s Daytona famously sold for US$17.8 million.

What drives these sky-high prices, Dr Moulding suggests, goes deeper than simple rarity value. “It’s like that Seinfeld episode about the golf clubs owned by JFK,” he says. “For the collector of the watch, it’s as though there’s almost a form of contagion. It’s as though the essence of the previous owner has been imbued into it.”

There’s surely some truth in this outlandish claim. Bourdain’s Rolex commanded its price tag for no other reason than it had belonged to him. As his intimate possession, in the collector’s eye it becomes psychically charged with his renegade swagger. Newman’s Daytona would’ve conjured a similar appeal, with the buyer perhaps hoping that some lingering spark of the actor would rub off, thereby helping him make far better salad dressings.

“Objects become part of our identity,” Dr Moulding explains. “And in that sense, they can also provide a sense of history and a physical link to the past.”