Could this obscure Submarine have been the first waterproof wristwatch?

Fergus NashDespite being a multi-billion dollar industry with hundreds of years of development, there don’t seem to be that many people dedicating their time to chronicling watch history. You have the rare enthusiast and some museum curators, but overall the amount of brands clamouring their achievements without much accuracy significantly muddies the water. As a technology that was largely collaborative and filled with simultaneous discoveries, early wristwatches are a particularly blurry part of history. However, every now and again you may stumble upon a forgotten legend which deserves a much larger place in the collective consciousness, and that’s very much the case with the Tavannes or Brook & Son Submarine.

If you mainly get your wristwatch history from reviews of new releases, chances are that brands like Rolex, Blancpain and Panerai will come to mind when thinking of the earliest waterproof watches. Digging a little deeper will reveal the Omega Marine — a tiny rectangular watch from the early 1930s purpose-built for underwater action. But to be perfectly clear, the history of waterproofing watches goes much further back than Omega, and even further back than the idea of wristwatches. Since the evolution of the pocket watch, watchmakers and engineers have always strived for better protection from the elements. Dustproofing and waterproofing were the natural goals for decades, and there were hundreds of significant developments from different people across the ages. Brands such as W. Pettit, Dennison, Borgel and countless others deserve a lot of credit for the technology which modern watchmaking relies upon. There are even stories of 19th century pocket watches getting sent through washing machines accidentally, coming out bone-dry and working perfectly. “Explorer’s watches” were sealed from the outside world in all manner of inventive ways, and travelled the world’s extremities with the likes of Ernest Shackleton.

As soon as wristwatches evolved out of necessity during WWI, the need for them to be dust and waterproof was readily apparent. Given the nature of the smaller cases however, established waterproofing used for pocket watches couldn’t just be transferred over without new designs and patents. Many companies and engineers tried their hands at solving the problem, however the earliest achievement likely came from the request of two submarine commanders. Although submarines were enough of an established technology to see widespread use in WW1, there was still a dubious amount of trust being placed in those tin cans. If you were going to risk your life below the waves, you’d want to make sure that your equipment was as reliable as possible.

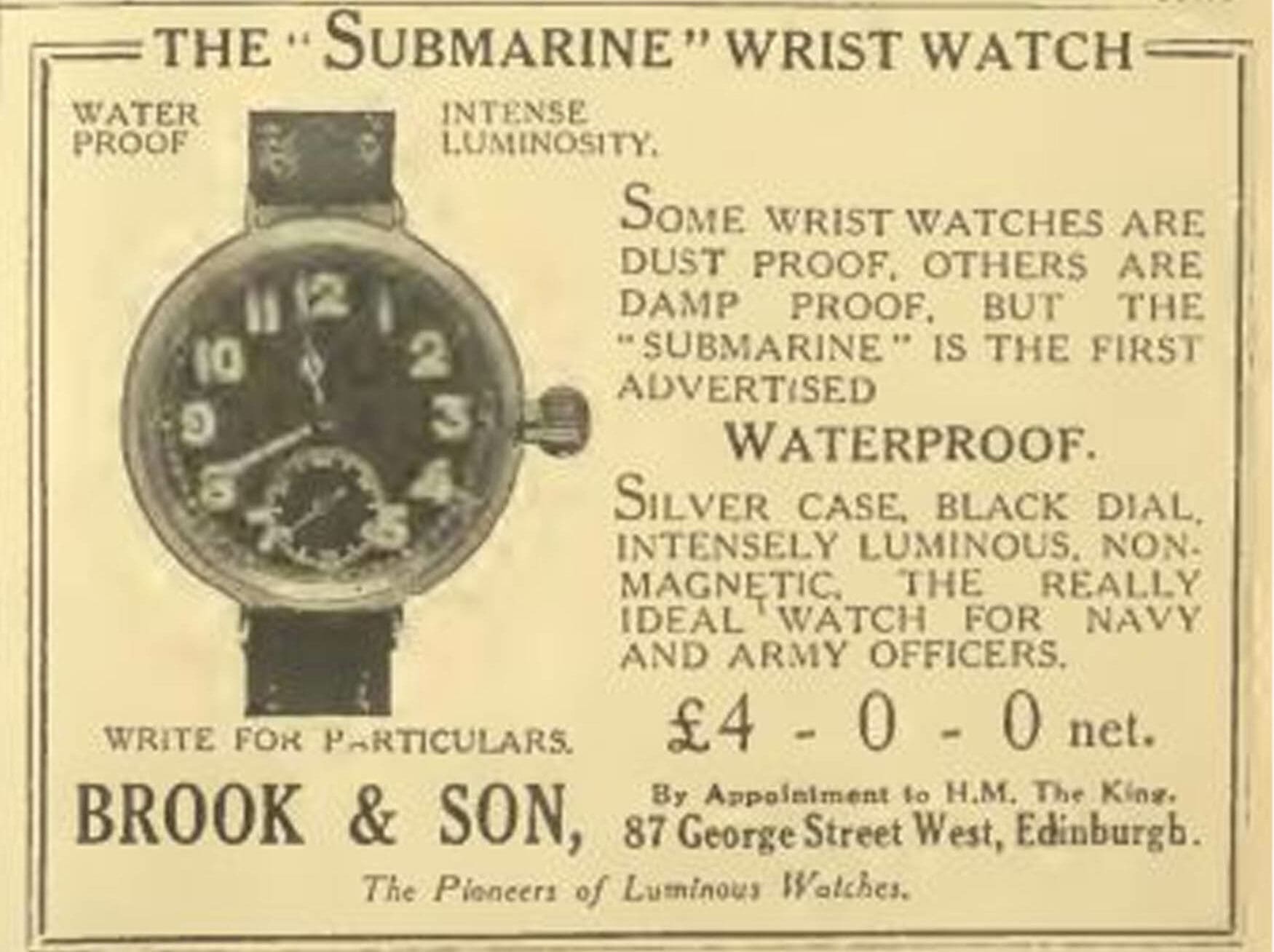

The story is vague and without names, but was published in the Horological Journal of December 1917 from the British Horological Institute. It speaks of the conditions laid out by the submarine commanders, made to Brook & Son in Edinburgh, Scotland. Firstly, it had to be completely waterproof to survive the damp conditions and frequent splashes that occur on any seagoing vessel. Secondly, a watch had to be anti-magnetic to survive the strong electrical currents that helped keep the submarine working. Finally, the balance needed to resist changes in temperature and keep accurate time no matter the fluctuations. The story with those specific instructions does come across like a bit of a marketing ploy, however a few repeated references and the appropriate timeline could lend itself to truth. The Scotsman newspaper from April 1916 also contains an advertisement for Brook & Son’s Submarine watch, saying that “The ‘SUBMARINE’ wristwatch purchased six months ago has been a great success.”

Regardless of the truth involving those two submarine commanders, the Submarine watch was a genuine product with genuine manufacturing behind it. If the first one was sold six months prior to the ad in The Scotsman, that would mean it had to have been designed and made around the middle of 1915 — coinciding with the start of extensive submarine warfare after the sinking of the British passenger ship Lusitania. Of course, Brook & Son in Edinburgh was just a prominent jeweller, and the manufacturer of the Submarine watch was a Swiss company called Tavannes Watch Co.. Tavannes operated initially between 1891-1966, but they were revived in 2008 and continue to produce modern takes on the Submarine along with other watches. The original Tavannes was a powerhouse though, working to make movements for brands like Cyma and becoming the fourth largest watch manufacturer in the world by 1938.

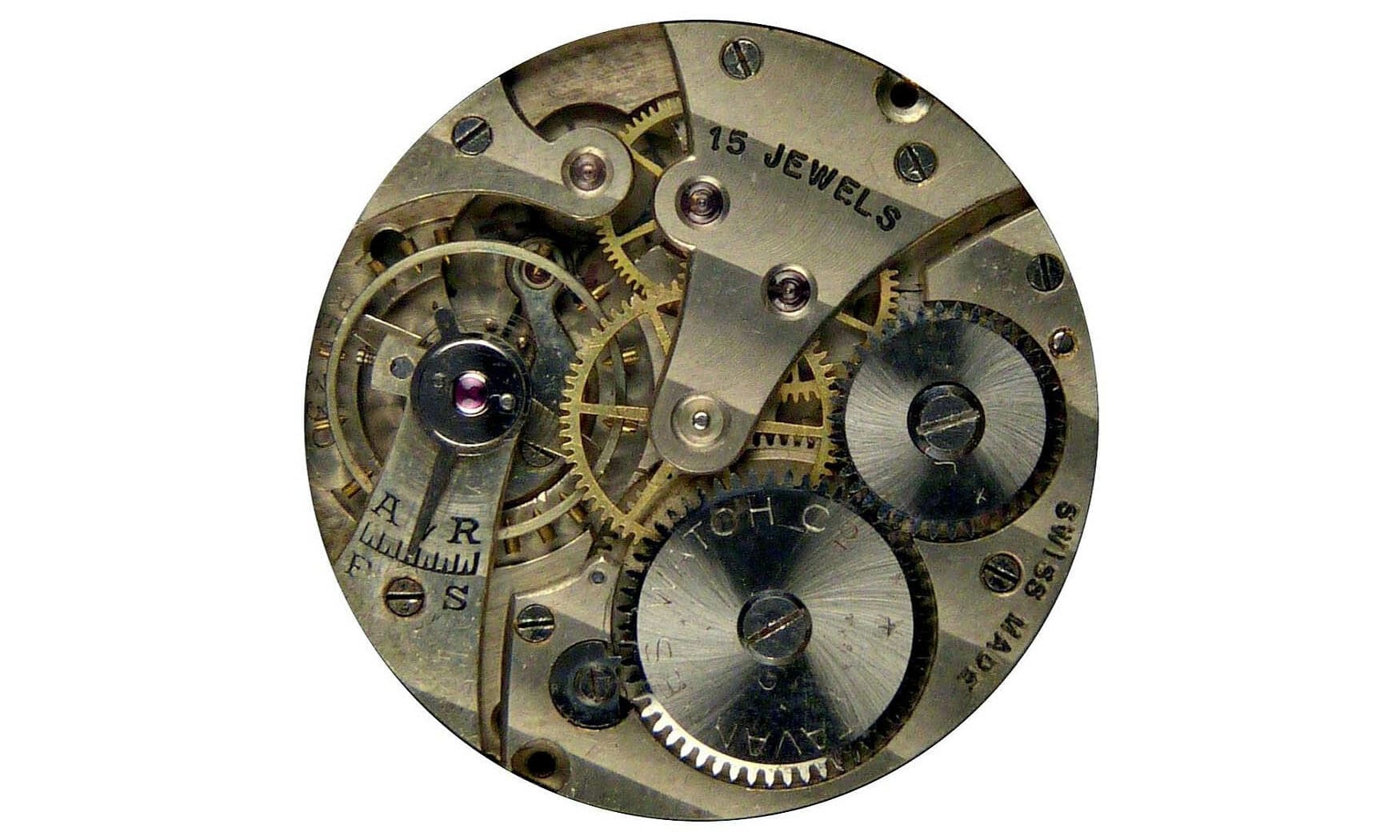

Tavannes achieved the waterproof Submarine case through the use of a screwing caseback and bezel, tightening onto gaskets and using a ‘gland’ to successfully protect the crown. The gland design allowed the Submarine to keep its waterproof properties even when setting the time, meaning there was no need for a screwing crown whose threads could wear out or corrode. In those days gaskets were made from waxed cotton or oiled leather rather than the sophisticated rubbers we know today. From the worn black paint on some of the surviving hand sets, you can also see that the hands were made of brass rather than steel. This would have been one of the anti-magnetic components that ensured accurate timekeeping. Aside from the watch’s significance of age, it did have one more incredible development. Balances are easy to take for granted these days with advanced alloys and silicon technology, but in the early 20th century there was still a lot of work to do.

The Tavannes 13 ligne 3B movement which powered the Submarine watch was outfitted with a balance spring made of Invar — an alloy of iron and nickel which was discovered by Charles Édouard Guillaume and noted for its low coefficient of thermal expansion. That means that compared to other metals, it didn’t change in shape or volume as much when the temperature changed. Paul Perret, an established inventor who filed the first ever Swiss patent, realised its significance for balance springs and collaborated with brands such as Tavannes to create consistent and reliable watches. Not only did it keep accurate time within a wide range of temperatures, but it was also completely non-responsive to magnetic fields. The Submarine watch can’t claim to be the first to use it like it can for waterproofing, but it’s an impressive example of early adoption.