Chronomentrophobia is the fear of clocks and watches. My son might have it. So what’s it all about?

Luke BenedictusSo we’re staying at my in-laws and my two-year-old is lying in his cot stubbornly refusing to go to sleep. Presently, I’m summoned to his room (again) by a frenzy of yells. “Daaad!” he says pointing to the mantelpiece. “That clock is scary!”

“How so? I enquire.

“IT’S GOT GOOGLY EYES!!!”

Peering at the table clock, I grudgingly admit the two winding holes for the chimes and pendulum embedded in the stepped dial do look a bit like eyes. So I cover the clock’s fearsome visage with a blanket.

All seems to be well and, after the customary round of delaying tactics (demands for milk / an apple / a cuddle / fewer blankets / a plastic dinosaur…), my son eventually surrenders to sleep. But several hours later, I hear an ear-splitting scream. When I go into Marc’s room, he’s standing up in his cot pointing to the clock on the mantelpiece. “Daaad!” he wails. “That clock is trying to eat me!”

I remove the clock from the room, calm my son and go back to bed.

So what was going on here? Well, a quick diagnosis by Dr Google – the logical place to go when confronted by googly-eyed clocks – is that my son might be developing “chronomentrophobia”, otherwise known as the fear of clocks or timepieces. If you’re not sure about the pronunciation, Outkast helpfully wrote a song about it.

Now phobias, in my book, are a bit like pornography. They exist for every conceivable niche that you can possibly imagine (gephyrophobia is the fear of bridges, ereuthophobia is fear of the colour red etc). Chronomentrophobia is apparently a more rareified cousin of chronophobia, which is the fear of time and of the passing of it. This is a condition that old people can become susceptible to as they become more aware of the proximity of death. Prisoners are also especially prone to chronophobia as they obsess over the length of their incarceration.

But I don’t think this is my son’s problem. The little fella’s grasp of time is still pretty shaky as demonstrated by his demands for chocolate first thing each morning. No, what seems to be going on here is a case of “face pareidolia” – the phenomenon of seeing faces in everyday objects. You know, this sort of thing…

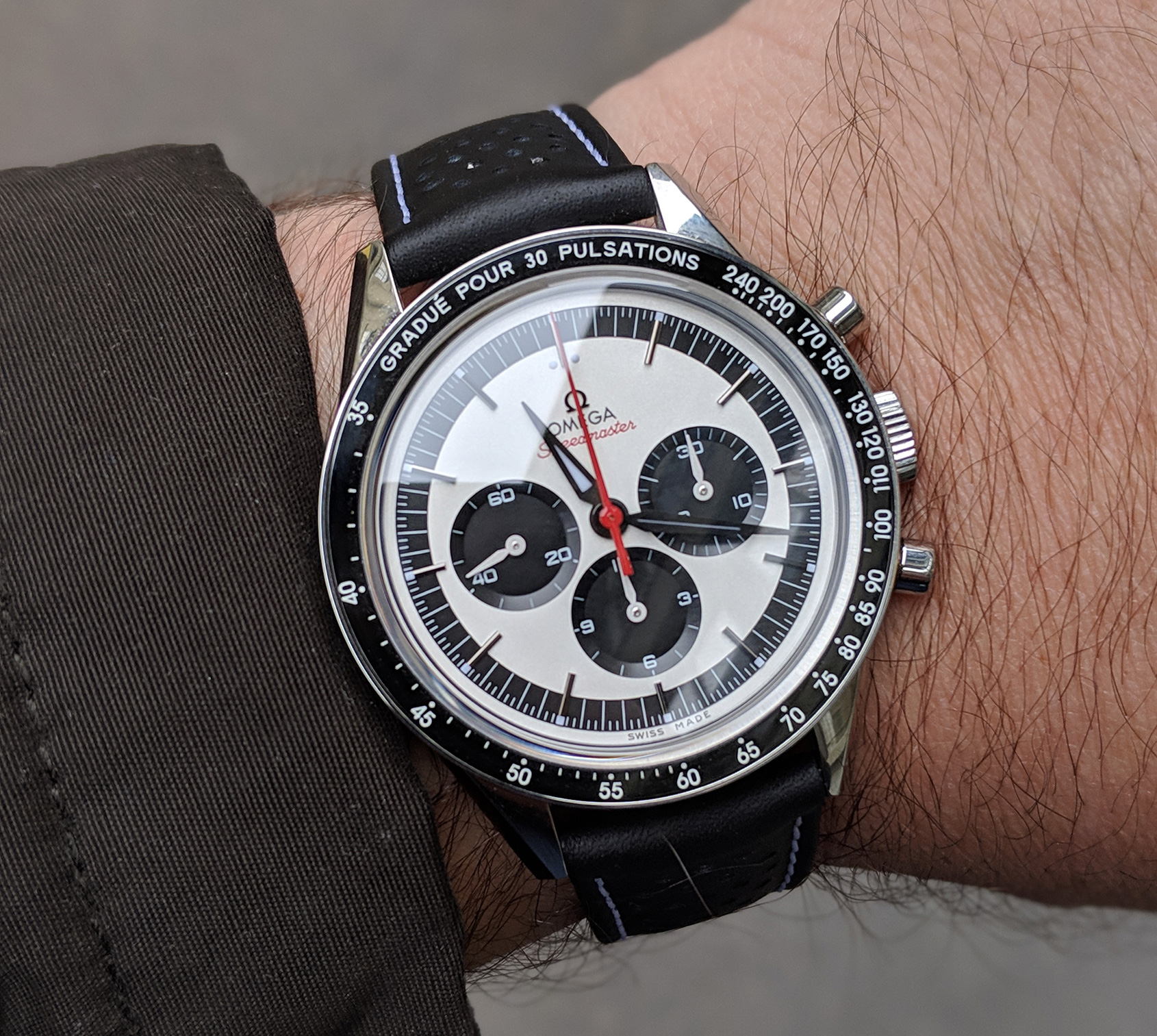

Pareidolia has long been tacitly accepted in the watch world. Panda dials, for example, are so called because they feature black sub-dials on a white background to resemble the physiognomy of – yep, you guessed it – a panda. Indeed, watch terminology often leans to the anthropomorphic with its talk of hands and watch “faces”.

When it comes to spotting faces in inanimate objects (or, say, the Virgin Mary in a grilled cheese sandwich) the human brain processes these imagined faces using the same visual mechanisms that we do for real ones, according to new research from UNSW Sydney.

Lead researcher Dr Colin Palmer told the university’s website.: “Pages on websites like Flickr and Reddit have accumulated thousands of photographs of everyday objects that resemble faces, contributed by users from across the world,”

“A striking feature of these objects is that they not only look like faces but can even convey a sense of personality or social meaning. For example, the windows of a house might feel like two eyes watching you, and a capsicum might have a happy look on its face.”

“Face perception isn’t just about noticing the presence of a face. We also need to recognise who that person is, and read information from their face, like whether they are paying attention to us, and whether they are happy or upset.”

My son’s insistence of the clock’s sinister intentions may therefore not be such a bad thing according to Palmer.

“There is an evolutionary advantage to being really good or really efficient at detecting faces,” he says. “It’s important to us socially. It’s also important in detecting predators. So if you’ve evolved to be very good at detecting faces, this might then lead to false positives, where you sometimes see faces that aren’t really there. Another way of putting this is that it’s better to have a system that’s overly sensitive to detecting faces, than one that is not sensitive enough.”

At any rate, my mother-in-law’s table clock is now winking at me from its new position on my desk as I write. Yet for all this face perception talk, the idea that it’s carnivorous is to me still utterly deranged. Clearly it’s just a bit peckish.