The perpetual calendar through the years

Borna BošnjakIf you ask the average watch fan what the most coveted horological complication is, chances are the answer is going to be “a perpetual calendar”. But like with most complications, there is more than one way to calculate the leap year cycle using a melange of cams, levers and gears. From its humble 17th-century beginnings to the 21st-century, six-figure wrist-machines calculating the most complex mechanical algorithms, I’ll do my best to briefly tell you the history of the perpetual calendar through three different time periods. Some of these watches are important for their leaps forward, others showcased novel ways of getting around the problem, but they all contribute to important periods in watchmaking history. Happy leap year, folks.

The early adopters

While calendars keeping track of leap years had been integrated into clocks in the late 17th century, its adaptation into portable timekeepers came in the next century, courtesy of Thomas Mudge. He is most often attributed the invention of the lever escapement – the most common form of regulating the energy release of the mainspring. What is less commonly known, however, is that he also likely created the first-ever perpetual calendar pocket watch. The No. 525 above hails from 1762, and was sold at Sotheby’s in 2016 for only £62,500. Kinda staggering considering its historical significance.

Number 574 from 1764, property of The British Museum and cased in gold rather than silver, reveals how Mudge chose to indicate the complication. It features the date display around the perimeter of the dial, while the day of the week is placed in an aperture to the right of the pinion. The circular aperture indicates the moonphase, but the most interesting one is in the bottom left corner. Indicating the month, but also the number of days in any given month, the month of February has an interchangeable display, showing 28 or 29 days.

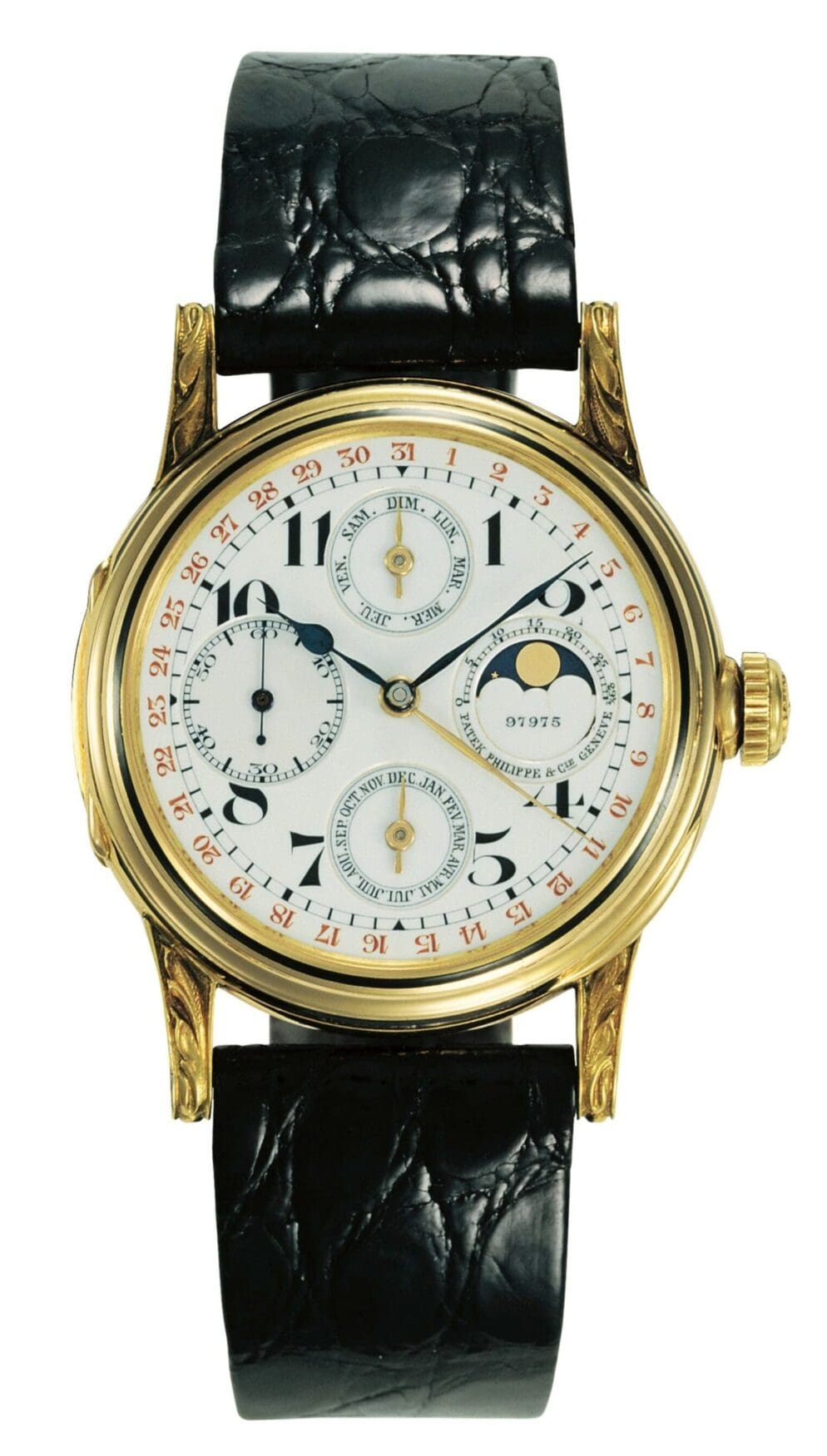

Perpetual calendar pocket watches continued to evolve, with efforts by Patek Philippe and Audemars Piguet, notably the school watch created by Jules Louis Audemars in the mid-1800s. It took until 1925 for the complication to make the switch to wristwatches, with Patek Philippe adapting the Victorin Piguet ébauche from a pendant watch into what would become the reference 97975.

While the Patek Philippe may have been the first wristwatch to sport a perpetual calendar movement, it’s actually Breguet that created the first QP specifically for a wristwatch. The reference 2516 had an instantaneous jump system, meaning that the indications for day, date, and month would all satisfyingly tick over at the same time provided you were observing the watch at the right time. This particular example was sold to Jean Dollfus, to be gifted to his brother Louis for 500 hours of flying – not the only complicated Breguet in the brothers’ collections.

20th century revolutionaries

Now an established feature in high-end watches, the natural evolution for the perpetual calendar would be for manufacturers to pair it with other complications. This kind of thinking would give rise to one of the most coveted and collectible horological complications, period – the perpetual calendar chronograph. Say what you want, but in my eyes, there is no watch that captures that essence of true haute horlogerie, classical design, and collecting mystique than the Patek Philippe reference 1518. This isn’t just any perpetual calendar chronograph – it’s the first one. It began production in 1941 alongside the 1526 – the first serially produced perpetual calendar. The 1518 was produced in 281 examples, while the 1526 was even rarer, counting only 210, though the former commands much more attention from collectors.

Combining a perfectly symmetrical register layout, a tachymeter scale and a wonderful 35mm case, it housed a Patek-modified Valjoux 13 ébauche created by Victorin Piguet, sporting a straight-line lever escapement with a swan neck regulator and a Breguet overcoil. It was a true showcase of the brand’s mightiness at the time, as it would take other manufacturers more than 50 years to catch up and produce a perpetual calendar chronograph of their own.

Given how tedious these early, manually wound perpetual calendars were to set, one would think that next sensible inclusion would be an automatic one. Or perhaps, you noticed that none of the watches we looked at so far indicated leap years. While I won’t spend too much time talking about those (maybe undeservedly), the 1955 Audemars Piguet ref. 5516 and 1962 Patek Philippe ref. 3448 both made strides towards making perpetual calendars easier to live with. With the AP, showing the leap year meant you wouldn’t have to remove the dial to set the watch properly, as the watch would indicate the months in a 48-month cycle – the first one to do so. The ref. 3448, on the other hand, added automatic winding, meaning it was more difficult for the movement to run out of power, thus decreasing the likelihood of needing to be set.

While these earlier improvements were important, the next leap in evolution came from IWC and Kurt Klaus, the brand’s technical director. All perpetual calendars prior to the 1985 Da Vinci Perpetual Calendar relied on a series of pushers hidden in the case band. Klaus’ design used an ingenious module fitted to the venerable Valjoux 7750, allowing the wearer to adjust all the perpetual calendar indications via the crown. Not only was this a much more intuitive solution, it also allowed IWC to experiment with different case designs, and opened the door to sportier perpetual calendars due to inherently improved water resistance without the correctors. With fewer components and less complexity, the movement was also cheaper to produce, and a version of it is actually still in use today by both IWC and Jaeger-LeCoultre.

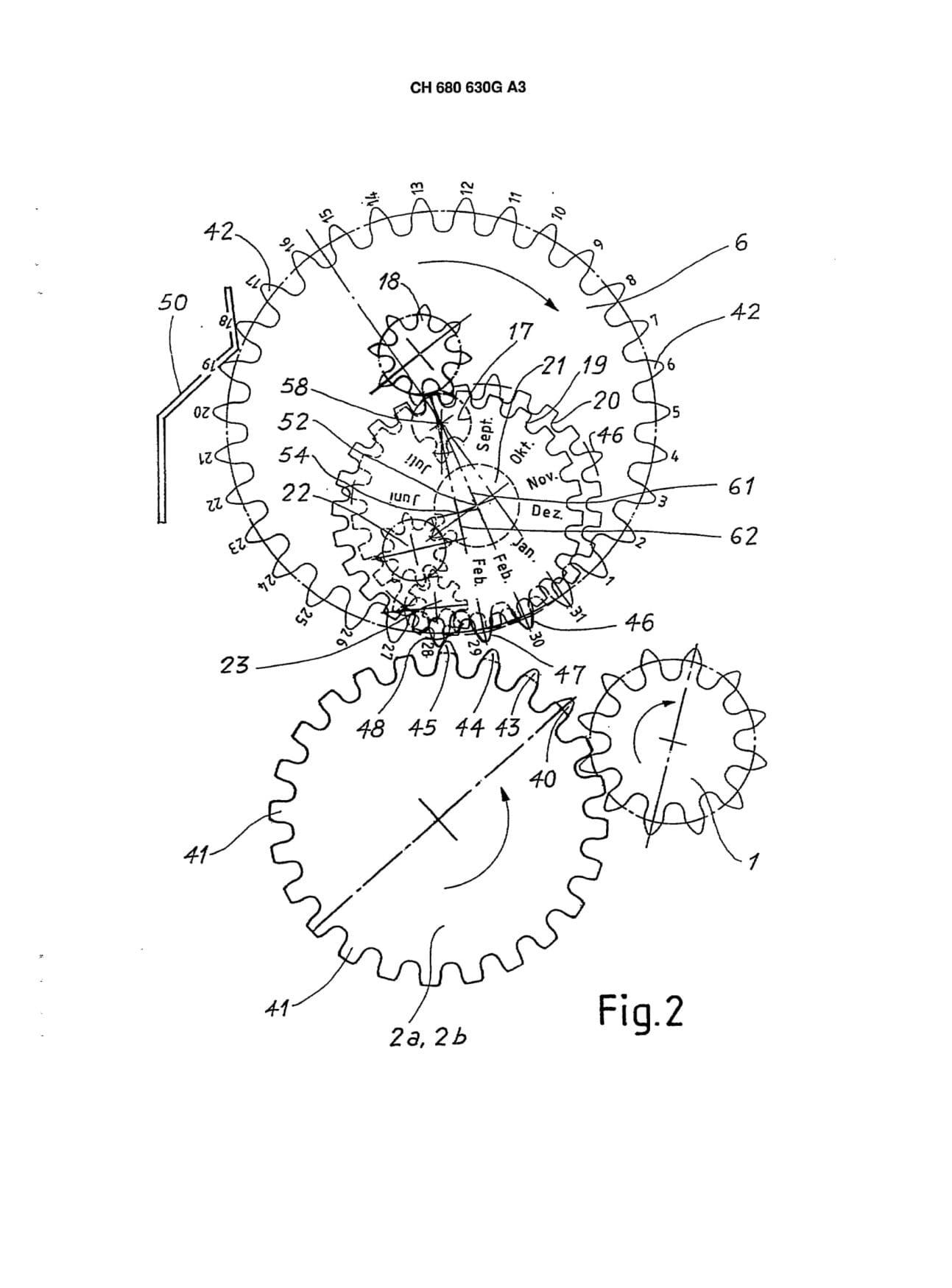

Consisting of only 81 components (compared to the hundreds found in traditional perpetual calendars), the module is powered by the main timekeeping component of the movement which advances the date lever each night, as well as the star wheel day and moonphase indications. At the end of the month, a longer tooth on the date wheel advances the month cam which rested at centre of the module. The shape of its indents informed the rest of the mechanism about the lengths of the months, indicating a full 48-month, leap-year cycle, with the deepest groove for the 29th of February. All of the shorter months are controlled by a pawl that, depending on how far down the groove it reaches, advances the date wheel accordingly thanks to its bigger movement radius.

The innovation wasn’t perfect, however, and came with some sacrifices. Rather than allowing you to change the indications individually, the wearer could only advance the calendar via the crown, as the algorithm came pre-programmed from the factory. This meant that you couldn’t adjust the movement backwards, thanks to the grand lever-centred design, so if you accidentally set the calendar too far forward, you’d need to wait for the power reserve to run down or do the walk of shame and hand it back to IWC for servicing.

It would take another decade, as well as one of the people involved in the Da Vinci project, to remedy the backwards-adjustment and dead zone issues that persisted. Enter Dr. Ludwig Oechslin, who alongside Rolf Schnyder, spearheaded the revival of Ulysse Nardin in the 1980s and ’90s (also designing the Freak). Oechslin, renowned for his restoration of Vatican’s Farnese astronomical clock, developing of the Türler clock, and creation of a Antikythera Mechanism replica, built on Klaus’ idea of a crown-controlled perpetual calendar mechanism.

The result was the 1996 Ulysse Nardin Perpetual Ludwig, which got rid of the traditional reliance on toothed cams and the grand lever, instead incorporating two coaxial wheels, with the 24-hour wheel consisting of two wheels differentiating between 31-day months and another for shorter months. A leap year wheel rotates once every four years, with three protruding teeth advancing the date for shorter February months. Setting up the perpetual calendar in such a manner, it allowed the wearer to adjust the watch forwards and backwards, eliminating the dead zone during which any adjustments may cause damage to the mechanism, while also improving reliability thanks to better shock resistance.

The resulting dial layout wasn’t the most pleasant in my opinion. It didn’t quite capture the golden ratio inspiration of the offset date like a Lange 1, but also wasn’t symmetrical enough to evoke mid-century beauty like Patek Philippe’s earlier watches. Nevertheless, the Lemania-based UN-33 calibre was revolutionary in its own sense, and would pave the way for Oechslin’s further work with perpetual calendars – more on which shortly.

Modern masterminds

For all the issues Oechslin may have solved with the Perpetual Ludwig, there was one issue, if you could call it that. Rather than having the crisp, instant transition at the top of the day, the perpetual calendar indications slowly creeped over to the next date and month. It took another decade before that “issue” was resolved, this time thanks to the H. Moser & Cie Perpetual 1. This was a critical watch for the brand, as it was the grail product they basically launched with, the company only being reestablished a year before the Perpetual 1 was officially released. Even then, the brand’s signature minimalist style is instantly recognisable – it’s the only watch on this list that could easily pass for a simple time-and-date piece.

Fear not – the Perpetual 1 had a few tricks up its lugs. For starters, the dial indeed indicated the months, with a tiny arrow hand projecting from the centre pinion, pointing to the 12 indices. The caseback is where you could find the leap year indication, but the clean design wasn’t the Perpetual 1’s only novelty.

To achieve it, they outfitted the gear-based, Andreas Strehler-designed HMC 341 calibre with the “Flash Calendar”, a dual-layer date disc that would not only be legible, but also allow the movement to instantaneously jump from February 28th to March 1st. The top disc was numbered from 1-15, while the lower contained numbers from 16-31. At the end of every month, the top disc would jump forward, instantly displaying the desired date. This feat was achieved by the mechanism’s interaction with four small latches between the 16th and 31st of the lower disc, protruding into the plane of the upper disc.

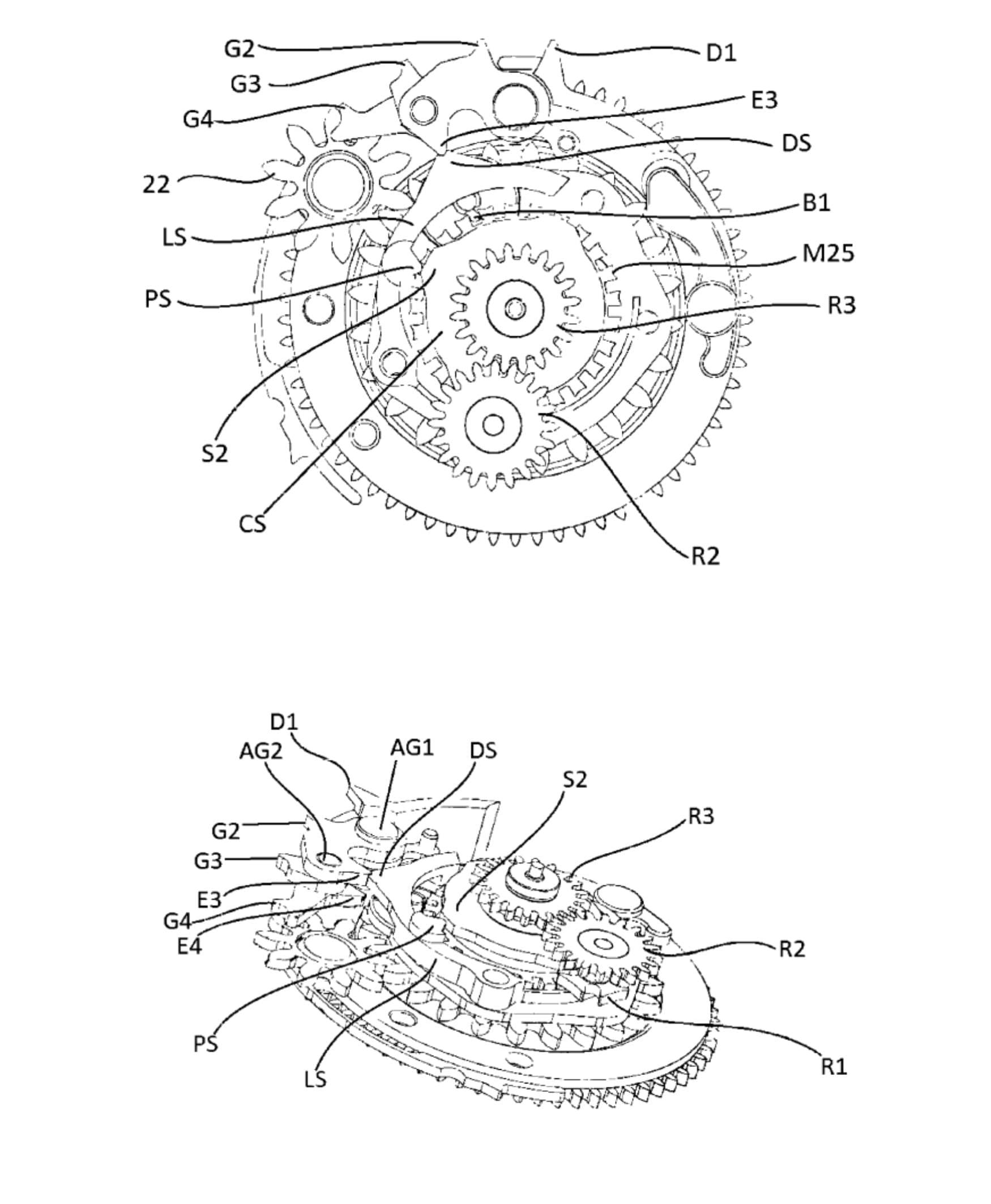

Remember Dr Oechslin? Well, he gets another mention on this list, thanks to what could be one of the most underrated watch brands out there. Three modified and nine additional components are what make the 2016 Ochs und Junior Perpetual Calendar a perpetual calendar, built on top of the Ulysse Nardin UN-118 base. And speaking of simple indication – it doesn’t get much simple than this. The brand promises that it becomes intuitive, too, and though I could see some teething issues, the sheer genius of this movement makes it a personal favourite.

For starters, the gear-based calibre not only allowed Oechslin to use fewer parts, but it also makes the indications adjustable via the crown, both forwards and backwards. In short, the movement works by the 124-tooth date wheel being advanced four teeth per day, interacting with the Maltese cross-equipped month wheel in the last three days of the month. The four-armed Maltese cross wheel indicates a leap year by one of its shorter arms, causing the lever that would normally push against a longer arm to retract, making the date wheel advance to the 29th of February. For an explanation about its operation, and much more about its inception, who better than Oechslin himself to explain?

From an extreme simplification of the movement, to something that’s the complete opposite. The movement of MB&F’s LM Perpetual counts 581 components – many on full display – along with the flying V of the balance bridge and extra-long balance staff. This is the first full movement design Stephen McDonnell undertook, and doesn’t use the crown to control it, rather separating the functions into pushers neatly integrated into the case. These interact with the stacked-gear mechanical processor that uses 28 days as standard for each month, adding additional days when necessary. In turn, each month will have an exact number of days, and the calibre won’t skip any indications, meaning adjustment is much simpler, too, as the user won’t have to cycle through four years-worth of indications. The biggest challenge McDonnell faced in creating this movement was eliminating the dreaded dead zone, overcoming it in unique fashion. Rather than designing a movement without a dead zone, he simply disconnects the pushers that could damage it during critical hours. Talk about a foolproof design.

With the perpetual calendar mechanism itself is simple or complex, the process of coming up with the idea and executing it is never easy. As a result, perpetual calendars are not always complicated, but always expensive. Right? Not quite. While you can pick up some bargain vintage examples from Audemars Piguet or IWC, they are a real rarity at retail, but they do – or rather, will – exist. Cast your mind back to the unfortunately doomed Only Watch 2023, and Furlan Marri’s Secular Perpetual Calendar piece unique. Before explaining how it works – a short crash course on what a secular calendar is. While regular perpetual calendars track most leap years correctly, they’ll stumble when we get to 2100. This is thanks to a quirk of the Gregorian calendar that prescribes every century not divisible by 400 as not being a leap year. Secular calendars account for this 400-year cycle – and the Furlan Marri Only Watch piece does, too. And if you thought a perpetual calendar is difficult to engineer, secular calendars are naturally even more complex.

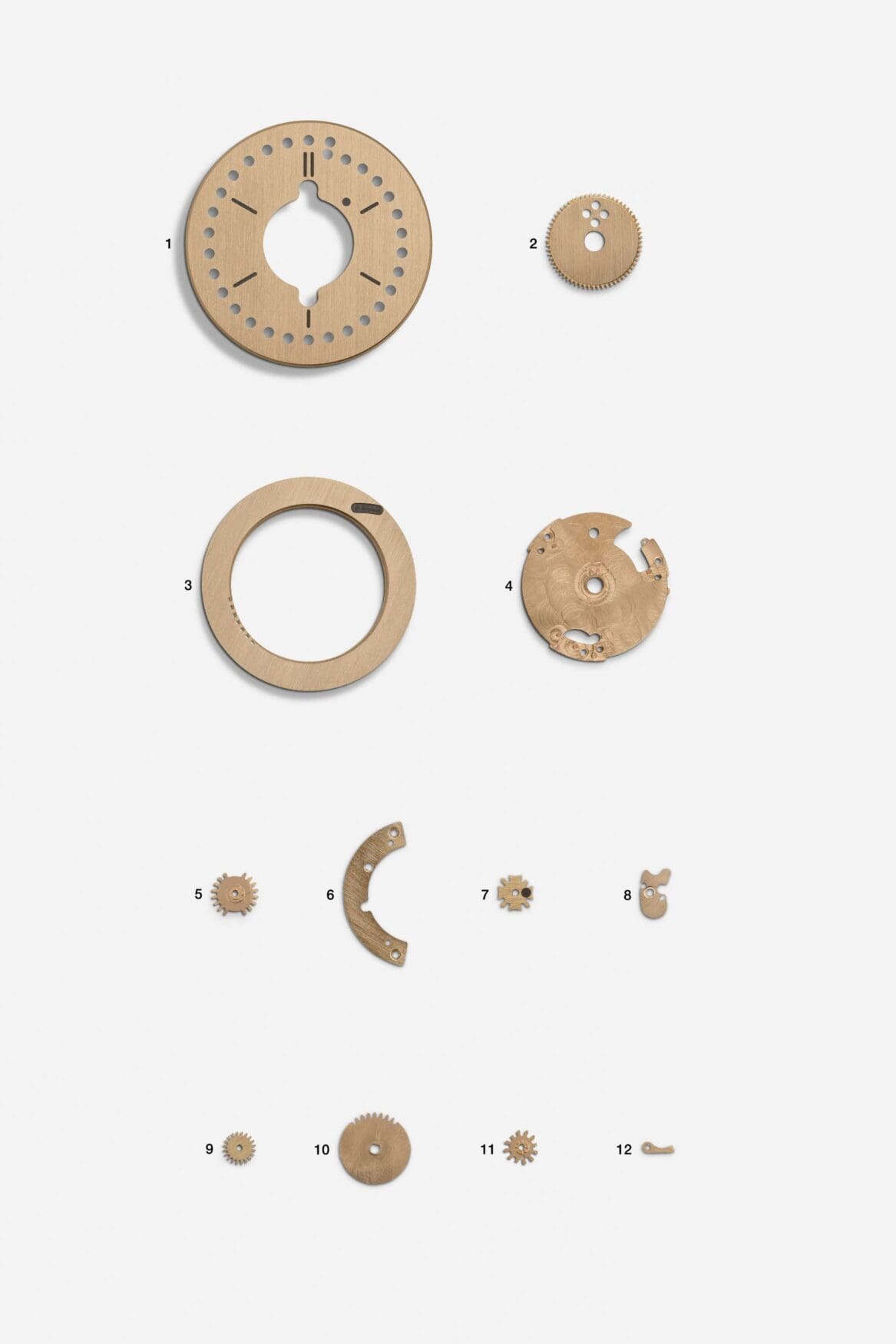

That is unless you’re Dominique Renaud (of Renaud & Papi, the complications house purchased by Audemars Piguet in 2003) or Julien Tixier, of course. Developing a special secular calendar module alongside Furlan Marri, this wonder of engineering uses only 25 components, meant to sit atop the entry-level three-hander La Joux-Perret G100. Thanks to the affordable base calibre and relative simplicity, Furlan Marri are targeting a ridiculously low (under CHF 20,000) price point for what’s on offer. I briefly mentioned this module a few times on the site, as a version of it featured in the DRT Tempus Fugit, a brilliant memento mori piece fully hand-made by Tixier.

A peripheral rocker that is driven by the 31-tooth date wheel, which interacts with a 48-month wheel to detect 30 or 31 days, drives a central month star wheel forwards. The secular calendar calculator is built around a 50-tooth year wheel that is driven by two fingers of the month wheel, turning it once every 100 years. The year wheel controls the position of the year cam feeler arm to indicate a 29-day February, while a Maltese cross wheel with one longer protrusion sits atop the year wheel and actuates the feeler cam for the leap year centuries divisible by 400.

Distilling all perpetual calendars into just a few inventions definitely takes away from many unique, beautiful and innovative solutions. If you’d like to continue being amazed by these tiny, beautiful creations, make sure to read up on the Vianney Halter Janvier Lune et Soleil, Breguet ref. 3477 and Greubel Forsey Invention 7 – all three add the equation of time complication to their perpetual calendar calibres. Greubel Forsey’s Computeur Mécanique is genius in particular, using a coded stack of discs and coaxially arranged wheels that can be programmed to automatically display the traditional perpetual calendar indications, along with equinoxes, solstices and equation of time. If one thing is for sure, is that perpetual calendars have come a long way, but still don’t solve certain calculations, like the date of Easter for example. Once that’s accomplished, this article will certainly warrant an update.