INSIGHT: The watchmaking of Piaget

David Chalmers

An image springs to mind when you think of the romance of watchmaking. For many people that image might include an historic chateau nestled in a small Swiss village amid rolling hills. Yet even with this idealistic pre-conception, it’s hard to find anywhere as picturesque as the home of Piaget.

La Côte-aux-Fées – the same village they’ve been in since 1874 – is exactly what you’d visualise in your mind’s eye: beautiful, remote and perfect for concentrating on the art of watchmaking. Just down the road from the landmark church is the unassuming white farmhouse where the brand was founded by Georges Piaget, a farmer who made pocket watches to supplement his income, until his son Timothée took over and timepieces became the full-time focus for the family business.

La Côte-aux-Fées

By 1940, the success of Piaget meant growth, and the company moved just 50m down the road to a building where the brand still produces movements today, with 30 expert watchmakers among the 120 staff. It overlooks a small valley where Yves Piaget – great-grandson of the founder— built a small ski-run. This is Switzerland, after all.

Picturesque as the scenery is, we’re here for beauty on a much smaller scale. La Côte-aux-Fées produces around 15,000 watches per year, of which around 150 are the ‘Grand Complications’ made by seven master watchmakers – minute repeaters, tourbillons, skeleton dials and perpetual calendars.

Wafer Thin

One of the defining hallmarks of Piaget is its dedication to thin watches – really thin watches – though this obsession is less about fashion than it is a way to demonstrate precision watchmaking. After all, the challenge of designing and manufacturing watches with micro-mechanical movements often no more than 3mm thick (or should that be thin?) is extreme. Not only does it mean manufacturing tolerances are low, it also requires a high degree of hand-finishing due to the delicacy of components .

Hand Finishing

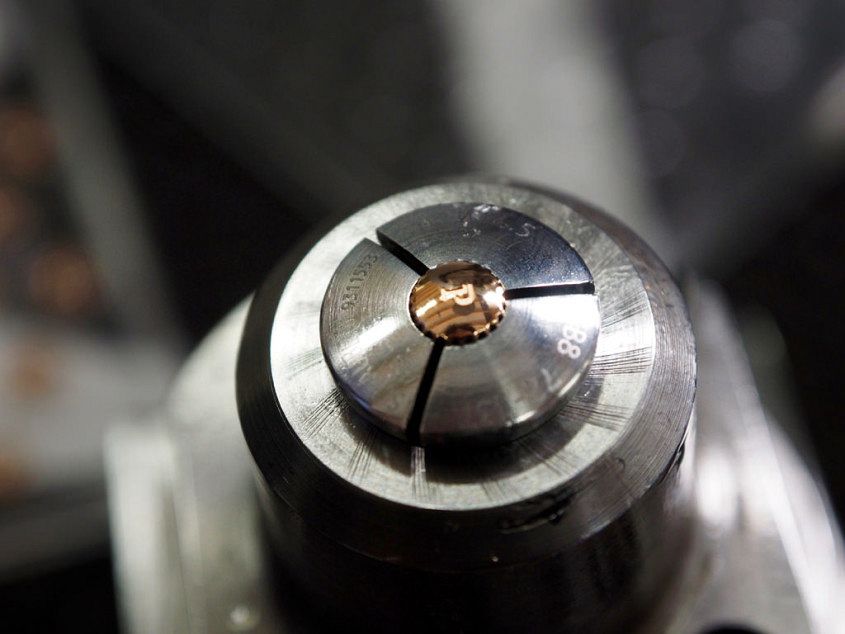

As with most modern watch factories, the movement’s life begins at the CNC machines – 20 of them, which are used to cut the rough bridges and plates. Beyond that, some components are entirely machine finished – a quick process that takes no more than 20 seconds per piece – but that’s the minority, with most done by hand. Sometimes this involves using an electrical tool, such as the one below, though even this sort of finishing requires up to two hours of work.

For the absolute top-end watches there are no electrical tools used in finishing. This means each component takes up to 10 painstaking hours to perfect, which helps address the often asked question on why Swiss watches cost what they do. Imagine what BMW would charge for a car if every element took a skilled craftsman that long to finish.

All this work means that even a basic baseplate can take two to three days to complete, while a minute repeater movement takes 1400 hours of finishing.

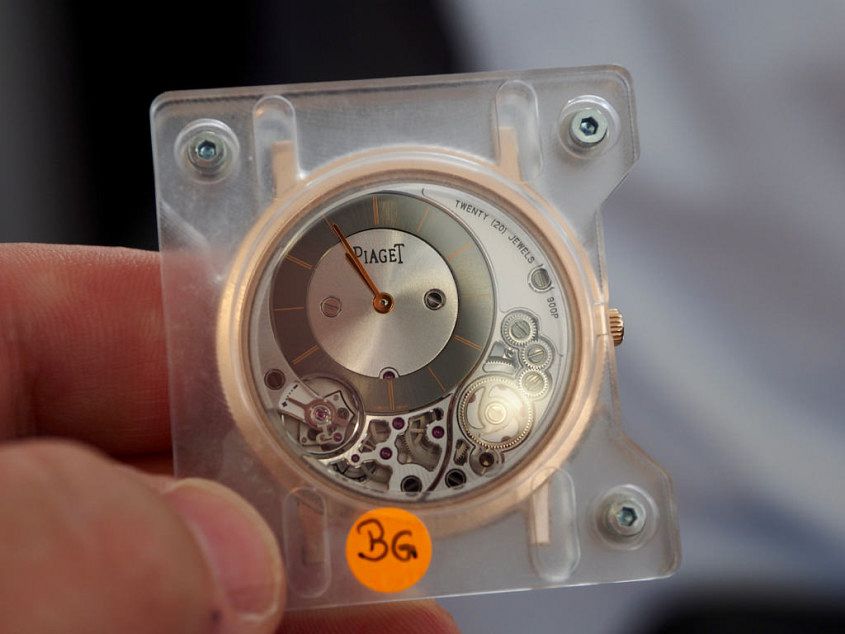

After the watch is complete, it’s wrapped in a plastic sleeve, checked for dust and shipped to the Geneva facility where the strap is fitted. Below is a beautiful 38mm Altiplano 900P in rose gold undergoing its final checks.

High End Complications

With this level of care, the facility is also able to make one-off pieces. During our visit we were lucky enough to see a of these few special creations, including this Polo Tourbillon made for a Russian collector, featuring a depiction of the battle of Stalingrad.

Plan-les-Ouates

About 90 minutes away from the quiet surrounds of La Côte-aux-Fées is the very different, very modern Piaget factory on the outskirts of Geneva. Plan-les-Ouates is essentially an outer suburb of Geneva that’s home to several brands which also include Patek Philippe, Rolex, Baume & Mercier, Frederique Constant and Vacheron Constantin. They’re here because there’s plenty of space and – critically – it’s part of “Geneva” meaning that watches made here are able to carry the prestigious Geneva seal.

Piaget’s Geneva facility was inaugurated in 2001 and today has 380 employees. This is home to the technical side of Piaget, with new watches and movements designed here. It takes between three and five years for a watch to move from sketchpad to working prototype – which means that plans for your 2020 Piaget are already underway.

Gold, Gold, Gold

Piaget is a brand that uses lots of gold – yellow, grey, white and rose – in its cases and skeleton dials. In fact, on higher end watches the majority of components are gold, right down to the screws.

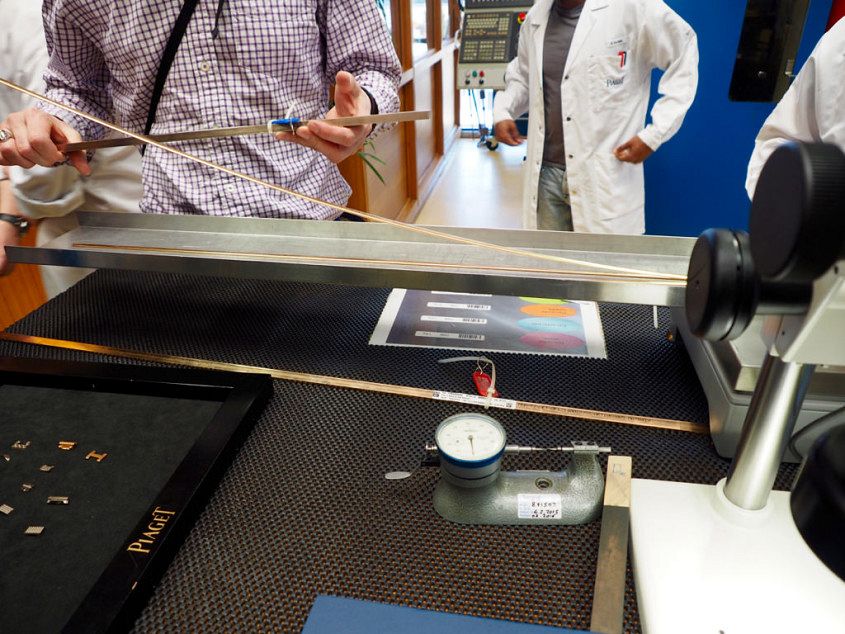

Each one of the gold rods in this photo weighs about 4kg, totalling a cost of $140,000. These rods will be turned into bracelet links, but the challenge in working with such a valuable raw material is how to minimise the off-cuts. Amazingly, the typical wastage of each gold component is 60%.

Given the sums involved, recovering every speck possible is a priority. That means collecting every scrap of metal in these yellow bins and using vacuum cleaners and air filters to capture the precious particles. The end result? 99% of wastage is captured and recycled.

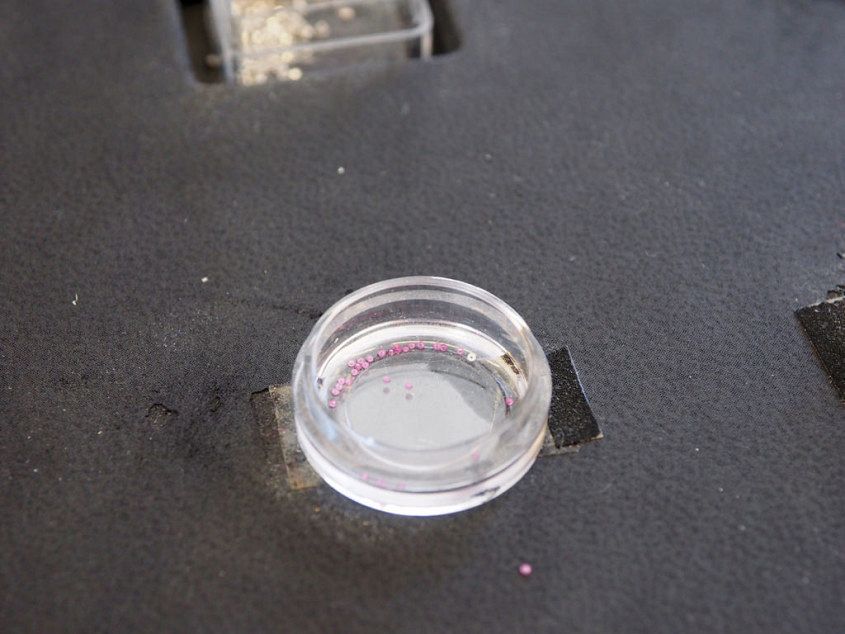

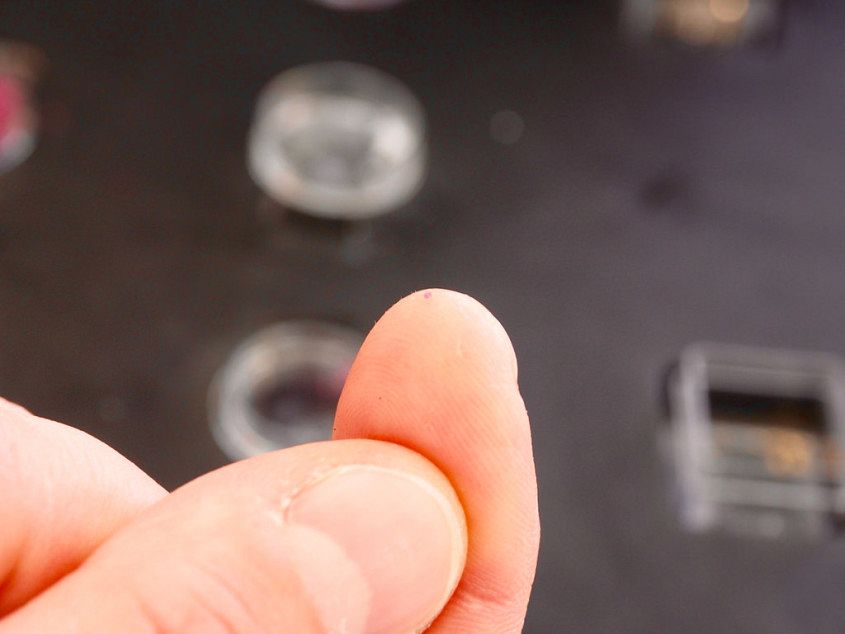

Returning to the bracelet links that were fashioned out of those gold rods, these are now added to ceramic pellets and water and given the first of many polishes.

And despite the modern factory, there is still a high degree of specialisation. Every single gold Piaget crown, such as the one below, is finished and engraved by the same person.

The gold Altiplano casebacks below are quite different to what you’d normally see, in that these are functional, with cut-outs to incorporate movement components and further reduce the thickness of the case.

Bracelets

But perhaps one of the most impressive pieces of craftsmanship at Piaget is the traditional method of making bracelets.

Their wire technique sees hand-turned metal coils crafted into a finished bracelet in five days. While others have moved to more cost-efficient conventional bracelets, for Piaget it’s important to keep traditions alive, so they’re currently the only brand still using this method. The bracelet is the last thing we see at Plan-les-Ouates and a reminder again of the sheer hours of labour that go into high-end watches: five days to make a bracelet; 1400 hours to finish a minute repeater; three to five years just to get a new watch to the prototype stage. Everything takes longer than it could, which brings us back to the brand’s motto: “Faire toujours mieux que nécessaire“- Always do better than necessary.