Why do brands give their new watches such dumb names?

Luke BenedictusSometimes I encounter a watch that makes me think of Kim Jong-il. Let me explain. With more than 1,200 official titles, the North Korean dictator boasted more aliases than the average member of the Wu-Tang Clan. These included “Guardian Deity Of The Planet”, “Ever-Victorious General”, “Lodestar of the 21st Century”, “Eternal Bosom of Hot Love” and “Greatest Man Who Ever Lived”. Imagine the size of his business card.

But I often think of the Dear Leader (aka “Sun of Communist Future”, aka “Invincible and Iron-Willed Commander” etc) when I come across a watch whose official name is so long that you can barely say it in a single breath. Example? Well, how about the Omega Moonwatch Professional Co-Axial Master Chronometer Chronograph 42mm. Or the Jaeger-LeCoultre Reverso Hybris Mechanica Calibre 185 (Quadriptyque).

Now don’t get me wrong, both of these are exceptional watches. The JLC is a technical marvel that required 12 new patents to develop and is the first watch ever to have four dials. The Omega meanwhile is a gold watch of sufficient magnificence that, in my book at least, it presents a genuine alternative to the iconic Rolex Day-Date. But while I was ultimately dazzled by both of these pieces, their names made me sceptical at first.

Partly, that’s because, as Kim Jong-il showed, overblown nomenclature reeks of self-importance. This, in turn, makes me suspicious. Are the grandiose names are a distraction tactic to cover something up? There is, after all, a time-honoured management strategy where a boss gives an employee a more highfalutin title as a substitute for the pay-rise or bonus they deserve.

At the other end of the spectrum you have Grand Seiko. They take the opposite approach to the name-game, often doling out names that are effectively serial numbers (unless you happen to be the son of Elon Musk).

In a way, I justify this tactic by the fact that Grand Seiko’s output is so relentless and their attention to detail so pathological, that I’d imagine they don’t have any time to waste on the naming process. They’re probably too busy perfecting the zaratsu polishing around their latest showstopper of a dial. Yes, their names may be unimaginative, but they’re the opposite of the Kim Jong-il approach and suggest the brand’s quiet humility and vocational zeal.

At the same time though, it doesn’t half make their watches confusing. Ask yourself, for example, which is your favourite Grand Seiko of the year so far? The SLGH009, the SBGE275, the SBGC247 or the SLGA009? Sadly, I don’t a photographic memory – I can’t even remember my wife’s mobile – so these names hardly conjure up an evocative mental picture.

The other problem with taking the serial number approach is that it then leads to watch nerds coming up with compensatory nicknames. Seiko’s beloved dive watches, for example, have such a cult following that devotees have devised countless nicknames that are more user-friendly and memorable than the original monikers. From the Turtle to the Monster, the Samurai to the Sea Urchin, the Willard to the Arnie… The list goes on.

Another brand with a similarly fanatical fan base is, of course, Rolex. And once again there are dozens of nicknames from the Batgirl to the Dirty Harry and the Pussy Galore to the Coke. These unofficial names largely stem from a place of playful affection, while reflecting the specific changes to a model as it’s evolved over time.

I appreciate this nickname convention is basically harmless and well-intentioned. My only objection to it is that it inadvertently creates another unnecessary barrier for the average consumer. To interpret these fan-boy labels you have to be “in-the-know”.

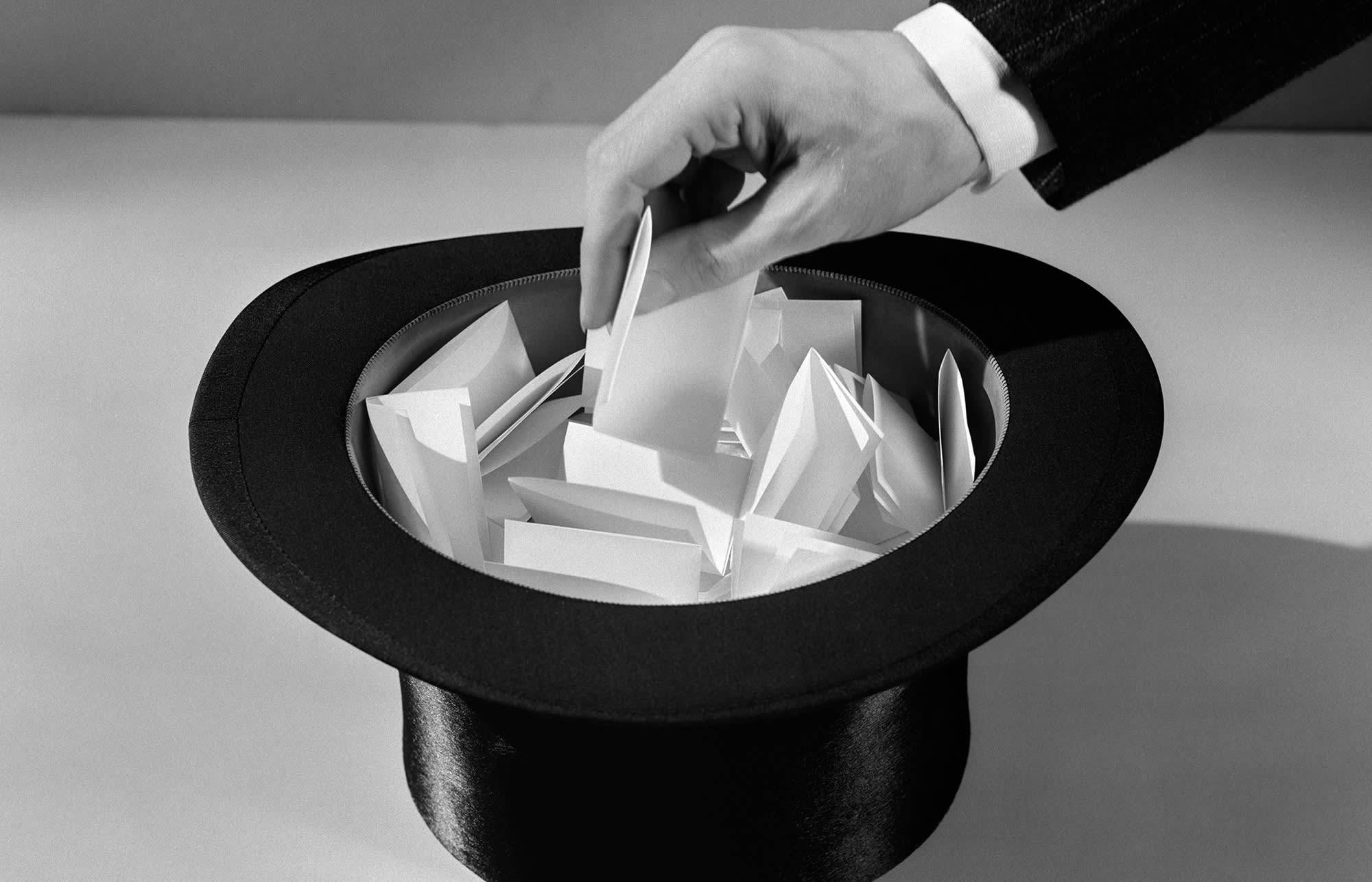

Personally, I remain wary of this circle-jerk aspect of watch culture that restricts timepieces to enthusiasts and the morbidly obsessed. That’s because the watch world is already intimidating enough for an outsider with its arcane French words and technical jargon. In a way, this mystique is in watch brands’ interests, too. Luxury objects need to feel “special” in order to justify their elite status and dizzy price-tags. Watch slang feeds into this cabalistic strategy, by creating another challenge for the intrigued outsider who simply wants to treat themselves to a new watch.

Ultimately, you don’t need to be an expert on nominative determinism to know that choosing a moniker is an important business. As Marshall McLuhan once said: “The name of a man is a numbing blow from which he never recovers.” I fear that the same goes for watches, too, as brands struggle to put a name to a face.