WHO TO FOLLOW: @WoodsWatchmaking, a third generation Australian watchmaker

Andy GreenMichael Woods loves travelling, playing basketball and is a proud dad. He’s also a third generation watchmaker who previously managed After-Sales for Rolex Melbourne.

Hi Michael, what’s your daily watch?

It depends on my mood, what inspires me, or what I’m doing for that day or week. It’s not uncommon for me to wear a few different watches in the same week.

What does your collection look like?

I have gathered quite a collection over the years, but I’ll mention the ones that mean most to me or the ones that get the most wrist time.

I have an Omega Constellation Day-Date from 1972, which was left to me by my grandfather who passed away in the early ’90s. He was the first watchmaker in the family, so it’s a very sentimental piece. I also have an IWC Automatic in steel from 1962, which I actually found on eBay. I was attracted to its simple, elegant look, and it is very comfortable to wear, so I restored the movement and it’s stayed in the rotation.

There’s also a Rolex Deepsea, which I purchased not long after the model was first released. I received training on the specifics of the case construction and I remember thinking that it was unlike any other production model released by the brand and I wanted one. It’s a big, heavy watch, but I still love the look of it.

I was at Baselworld in 2012 when I first saw the Tudor Black Bay, with burgundy bezel, and loved it immediately. The gilt dial and rose gold combo are amazing. Later that year I became a father, so when I purchased the watch, I made sure to have the caseback engraved with a message for my daughter. She already loves rotating the bezel. A few years later, Rolex gifted me the Tudor Ranger, and my son was born soon after, so I had the caseback engraved for him. Like the Black Bay, it’s a watch that is linked to a very important stage in my life.

I had admired the IWC Big Pilot for years. I remember seeing one of the earliest ones and just thought it was so cool. When I saw the blue dial model (Le Petit Prince), that sealed the deal for me, and last year I got it. Another big watch, but I love it from the dial to the strap.

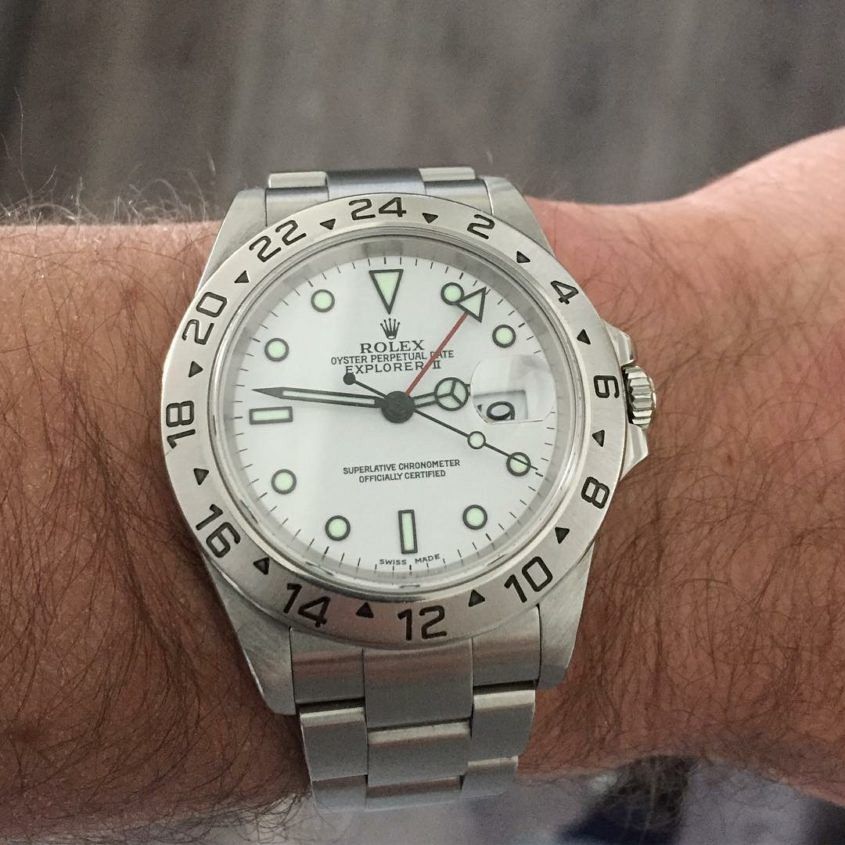

Just recently I purchased the Rolex 16570 Explorer II with white dial. That is a great-value watch. As it has the hour hand that you can move independently and the GMT hand, you can use it as a travel watch. Because of the fixed bezel, the watch sits flatter than the GMT and you also don’t have trouble with getting sand or dirt stuck under it. I also think that the white dial has a very clean look.

Tell me about a couple of your other vintage pieces. I know there’s a bit of an old family connection to several top-tier brands.

I’m very fortunate to be connected to a family business that sold Rolex, Tudor and Omega many years ago. Occasionally we get the opportunity to buy some of these pieces back and I have managed to get my hands on watches like an Omega Admiralty with a gorgeous brown dial. Also, the very early Rolex Air-King, beautifully simple Rolex 1016, Tudor Snowflake 9411 and a Jaeger-LeCoultre Military pocket watch.

Years ago, my brother gifted me this large, pear case pocket watch with a verge escapement, which I haven’t had a chance to restore yet. I find it very interesting because it contains little slips of paper from watchmakers who have carried out repairs over the years.

My other Grandfather, who is lucky enough to be turning 90 soon, gifted me this Seiko Bell-Matic with a chocolate dial. I love the story behind this one. He purchased it in Nadi in 1963 while on a trip with the Geelong Cats after they won the 1963 premiership. He still thinks that he has the original receipt somewhere. We’ll keep searching.

From an experienced watchmaker’s perspective, what makes a watch ‘good’?

A good watch, or a quality watch, is not as easy to define as you would think. It’s a big question to answer. To make it easier, I’ll just focus on modern mechanical watches that are considered luxury. So, reliability should be a standard. It should keep time to within approximately 5 seconds a day. This can vary slightly, and each brand has its own performance criteria.

There is always a lot of discussion in regards to the quality of watch movements. This level of quality is often gauged by the level of movement finishing and how nice they look. I appreciate and admire very high-grade movement finishing but this alone does not mean that the movement is of high quality. There can also be a level of quality in the production of wheels, pinions, levers and general movement construction that does not often get recognised. These signs of quality are usually only noticed by watchmakers that get to disassemble, adjust and assemble the movements. Usually, the best quality movements are very easy to disassemble, and when putting them back together, all the components fall into place with very little effort involved. They’re a pleasure to service and are not unnecessarily complicated.

The case, dial and bracelet design should also be considered when judging a watch, as they contribute to whether a watch is considered aesthetically pleasing or feels nice to wear.

What’s it like becoming a watchmaker in Australia? Were there many hurdles?

It’s not the easiest profession to get into for most people, because it either involves finding someone to take you on as an apprentice and invest time and money in you for several years, or you attempt to get into a watchmaking school in Switzerland and pay the costs of living in an expensive country for a couple of years. It isn’t as easy as just paying the costs to do that either, because it’s a challenge just to get accepted into a school like WOSTEP (Watchmakers of Switzerland Training and Educational Program).

It was still a challenge for me, but compared to most people, I was fortunate to have a father and uncle who are watch and clockmakers and who were very happy to take me as an apprentice. In fact, my Grandfather opened Woods Jewellers in 1956, and since then many family members have followed in different facets of the trade. My father is still working as a watchmaker, my uncle as a clockmaker, my brother as a watchmaker, my cousin is a watchmaker and my sister is a gemologist.

Tell me about your journey, from your apprenticeship to Rolex, to your own business.

Initially, I was against the idea of becoming a watchmaker. Being the oldest grandson, who was working in the family business at weekends for pocket money, I felt that I was expected to follow the same path as my family before me. No one else put that pressure on me, I just felt the expectation. After trying a couple of different courses at university which bored me, I found myself back at the family business, helping out. My father and uncle suggested that while I was working there I might as well try one of the trades.

My father spoke with Michael Presser (the watchmaking instructor at RMIT at the time) and inquired about starting an apprenticeship. Mr Presser asked my father if I had disassembled and assembled a watch movement before. My father lied and said yes.

Once he got off the phone, he sat me down at one of the benches, placed an old movement in front of me and told me to take it apart and put it back together. I was immediately hooked and it was meant to be after all.

I began my apprenticeship in 2000 and started travelling to Melbourne every few weeks to attend the watchmaking training at RMIT. I worked very hard at becoming as skilled as I could be. I would even go back to the Woods Jewellers workshop after dinner some nights to restore vintage watches. I had found something that I truly loved doing and because of that, I spent a lot of time practising. I made a lot of mistakes and damaged a lot of watches in the process but I think this was an important part of my progression. I was never afraid to make mistakes and even welcomed them because that is when you have the greatest opportunities to learn.

How did you go from there to Rolex?

After a few years, I moved to Melbourne and had the opportunity to work at Collections Fine Jewellery in South Yarra. It was a difficult decision to move away from the family business but I felt that I needed exposure to some different work to enable me to gain more experience. While there, I worked on lots of Rolex, Patek Philippe, Vacheron, Omega and other high-grade brands. I was working alongside Paul Madden, a watchmaker who had previously trained at WOSTEP in Switzerland. I learnt a lot working with him and we became good friends. After a while, he left and handed over all of the watchmaking responsibilities to me while he pursued a career in teaching at WOSTEP.

After Paul established himself at WOSTEP as an instructor, he convinced me to apply to also further my training there. I was lucky to be accepted, and in 2004 I flew to Switzerland to live in the town of Neuchâtel. It was an intense, six-month training program and one of the best experiences of my life. I worked alongside students from the UK, the Netherlands, Japan, US, Spain, Sweden and Greece. We lived together also, so became very good friends. We worked very long hours and even weekends but we made the most of it.

After completing my WOSTEP training, I spent some time in Ireland with my future wife (who is from Ireland) and we had to decide where to work. I had been offered quite a few job opportunities from training at WOSTEP and it came down to us living in either London or Melbourne. We decided on Melbourne and I began my career with Rolex in Melbourne.

I enjoyed it right from the start and I was working with a really great team. After three years, I was given the opportunity to become the Workshop Manager, which was a huge learning curve as I was still the youngest watchmaker in the team, but I threw myself into it.

I was privileged to be able to spend time at the Rolex factory in Geneva, where I trained on all of the models up to the Sky-Dweller and was even lucky enough to spend time with the restoration department where I learnt the finer points involved in authenticating rare and collectable models like the Paul Newman Daytona, ref 1655 Explorer II, Red Subs and Double Red Sea-Dwellers.

Over the years at Rolex, I was able to work on lots of rare and collectable watches, which included Milsubs, Paul Newmans and other Daytonas with very rare dials. Some of them are now valued in excess of $1,000,000.

I was also part of the team that designed the new Rolex workshop in Oliver Lane. That was another great experience.

With our kids getting older, my wife and I felt it was time to move back to the country and closer to my family. We built a house in 2017 just out of my hometown of Colac, with a great view of the lake. I get to see my family every day, and my kids get to see their grandparents and aunty and uncle much more.

The move gave me the opportunity for another career challenge, so I decided to start my own watch repair and restoration business. It wasn’t an easy start but after almost 12 months, I have established some good working processes. I just have to allow much more time to either source or make certain components, but I get to work on a large variety of timepieces.

Let’s talk about the Rolex Oyster Precision 6426 you just serviced. What was involved with bringing that beauty back to life?

I was really happy with how the Rolex Oyster Royal Precision ref 6426 turned out. I didn’t take any pictures during the process of cleaning the dial and restoring the hands, but I can explain it. Firstly, the dial was quite dirty. It is quite risky when cleaning a dial, especially when it is vintage. A lot of watchmakers don’t want to take the risk, which is understandable because it could easily be damaged during the process. I will always make sure to remove any dust or lose pieces of material from the dial before starting by using a blower or a light brush. Then, I sometimes use the fumes of various chemicals to improve the surface of the dial. This method is very risky because if the chemical makes contact with the dial, it will destroy it. You are basically holding the dial over the chemical as close as possible, and you have to make sure to hold it securely as to not drop the dial into the chemical. You also have to limit the time you do this, because you can risk damage by doing it for more than 20 seconds. This usually brings a little more life back to the surface.

With the hands, the old luminous material was breaking up and falling out, so I scraped all of the old luminous material off the back of the hands, cleaned them, polished them slightly then I had to match the colouring of the luminous as close as possible to the luminous on the dial. This is done by mixing different coloured paints to achieve a certain patina look. I also mix some new luminous material in with the paints so that the texture doesn’t look too smooth. When done right, the colour and texture will match that of the luminous on the dial.

What are the most common misconceptions you hear when meeting new customers?

Most customers are better informed these days about watchmaking and the work involved. I think in the past, customers used to compare it to servicing a car. So they would expect the watch to be serviced within a day or two and have the price reflect that of a simple oil change. The difference is that a watch can be running 24 hours a day, most days of the week, if not every day, and then it’s only serviced approximately every five years. It does a lot of work for you and there are very small components that may need to be restored.

What sort of work do you accept? What’s the most interesting watch you’ve serviced since going independent?

I accept any mechanical watches for small repairs or complete servicing and restoration.

I recently serviced a Hamilton pocket watch that wouldn’t be considered very valuable compared to some other watches, but I found it very interesting in the way it was constructed and its quality was extremely high. They are still very underrated in terms of quality.

Tell us about your approach to servicing/repairing/restoring priceless vintage watches.

My approach to rare and collectable pieces doesn’t differ that much to any other piece. If the watch has a market value in excess of $100,000 or less than $1000, I still have to approach every operation with care because there are watches that hold great sentimental value. I have had customers who cherish their watches even more because of sentimental value. Of course, if the dial is very rare then you have to be extra careful as a replacement will most likely not be available.

What is your favourite watch/brand to work on, and why?

That’s an easy question. Rolex. I have great experience from working with the brand, but even before working for Rolex, I found them very nice to work on. This comes back to what I discussed earlier about quality. Rolex movements are manufactured and constructed so well that all of the components just seem to fall into place so well. They are also great timekeepers. I serviced my Rolex 16570 Explorer II recently and after wearing it for two weeks, it had only gained 1 second. Not 1 second a day, 1 second over two weeks. I started checking it every day and it never seemed to deviate. Now, that is exceptional and a little uncommon, but I generally find them very stable.

Lastly, what’s your grail watch and why?

Without a limit to what I could spend, something from an independent maker like Kari Voutilainen or Roger Smith. They are amazing watchmakers. Otherwise, I would love to make my own pieces one day. That would be the ultimate grail.