What do the different types of stainless steel actually mean for your watch?

Jamie WeissEarly human civilisation is categorised into three stages: the Copper Age, the Bronze Age, and the Iron Age. Thousands of years later, we are definitively living in the Steel Age. Steel is one of the most commonly manufactured materials in the world, with over 1.6 billion tons of steel produced annually across the planet. Naturally, steel – or more specifically, stainless steel – is also the most common material used in modern watchmaking. We take it for granted as the default option for watches.

However, not all stainless steels are made equal. Just as we take the use of steel in watchmaking for granted, we as watch enthusiasts often gloss over the different grades of stainless steel and what they all mean. To help you cut through the marketing spin, here’s a concise guide to the main grades or alloys of stainless steel used in modern watchmaking.

What is stainless steel?

Let’s start with the basics. According to the Encyclopaedia Brittanica, stainless steel refers to any one of a family of alloy steels usually containing 10 to 30% chromium, the presence of which makes stainless steel highly resistant to corrosion and heat. Other elements, such as nickel, molybdenum, titanium, aluminium, niobium, copper, nitrogen, sulphur, phosphorus, or selenium, may be added to increase corrosion resistance to specific environments, enhance oxidation resistance, and impart special characteristics.

Stainless steels were first invented around the turn of the 19th century, with the English term “stainless steel” becoming prominent in the 1920s. Stainless steel started being used in watchmaking in the 1910s, when the material was beginning to become commonplace in manufacturing but took off during the Great Depression of the 1920s and 1930s when the demand for precious metal watches decreased dramatically.

316L stainless steel

Today, a variety of stainless steel alloys are used in watchmaking, but much like how most gold used in watchmaking is 18k gold, the vast majority of stainless steel used in watchmaking is 316L stainless steel. Sometimes also called A4 stainless steel or marine-grade stainless steel, 316L steel is also ubiquitously used in plumbing fixtures, food processing, medical devices, architecture and the petrochemical industry, just to name a few applications.

316L is what’s called austenitic stainless steel, which is one of the five classes of stainless steel by crystalline structure along with ferritic, martensitic, duplex and precipitation-hardened steel. Without getting too in the weeds, essentially what this means is that it’s highly heat-resistant and non-magnetic. Specifically, its primary alloying constituents after iron are chromium, nickel and molybdenum, with trace quantities of silicon, phosphorus and sulfur also present.

Why is 316L steel so popular in watchmaking? There are two main reasons: its mix of chromium, nickel and molybdenum gives it increased resistance to corrosion, and it’s also more malleable than other types of steel, making it easier to work with.

904L stainless steel

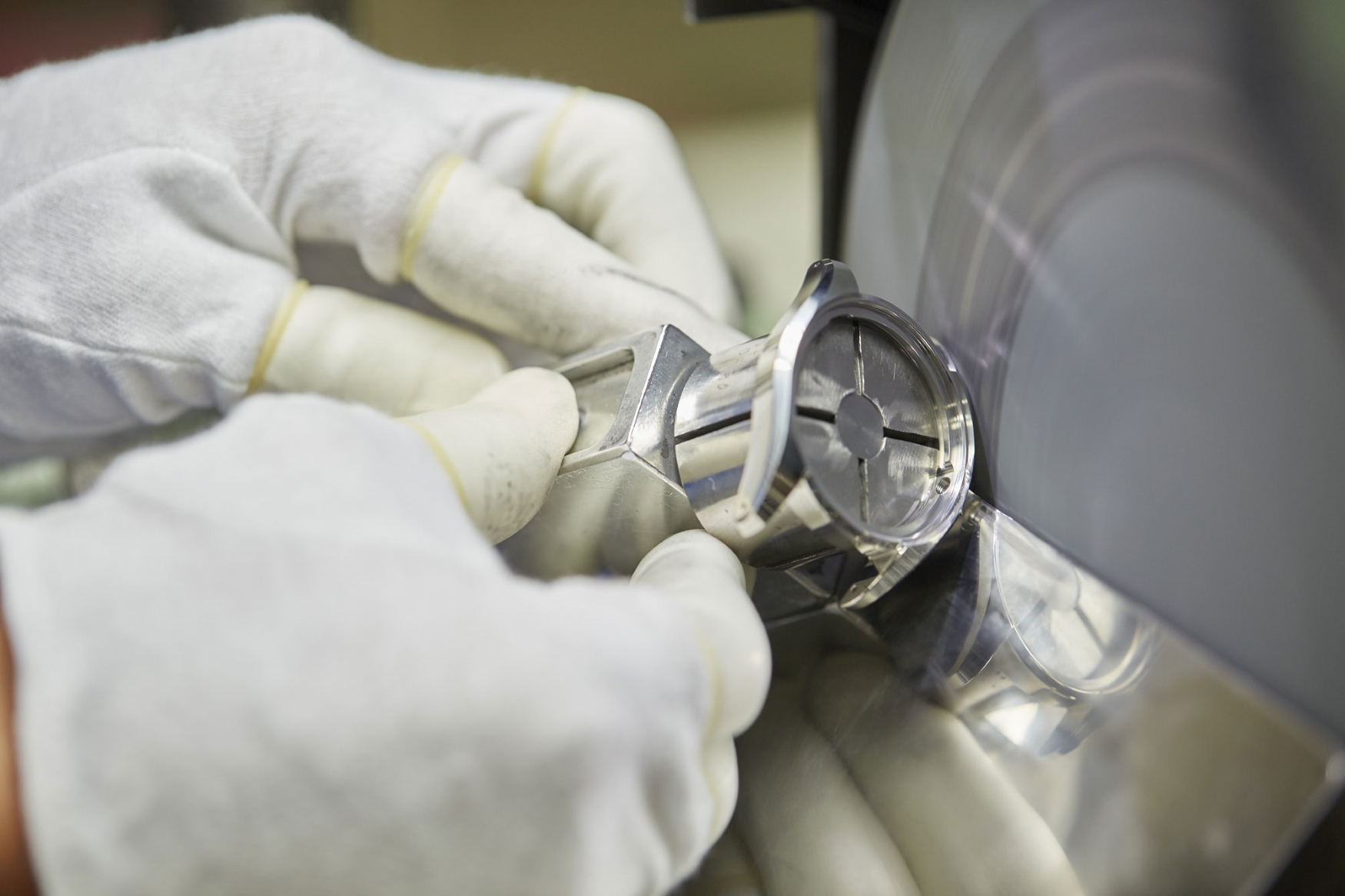

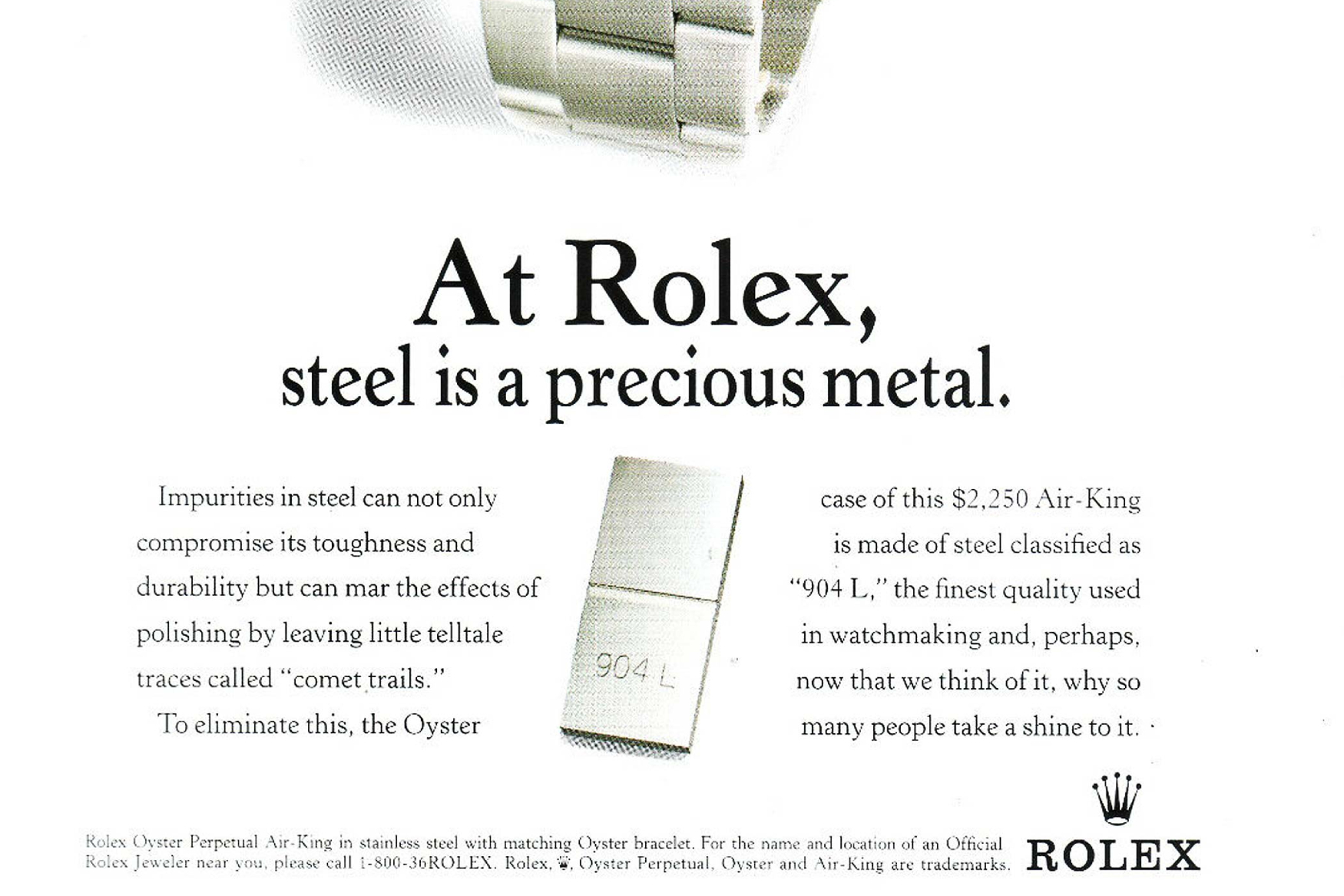

Another stainless steel alloy you might have heard watch brands refer to is 904L stainless steel. Rolex has famously used a proprietary 904L alloy that they call “Oystersteel” for all of their steel watches since the ’80s, but contrary to popular belief, Rolex isn’t the only watch brand that uses it. For instance, Bremont has started using 904L steel, making a real point of it in their current marketing. Other brands that utilise 904L steel in some of their products include Ball, Girard-Perregaux, Omega and Seiko.

904L is more expensive than 316L – indeed it’s one of the most expensive grades of stainless steel – and features a higher proportion of nickel and molybdenum than 316L. This makes it softer, but more corrosion-resistant. It also makes it appear lighter and lets it take a higher polish than 316L. It’s also worth pointing out that because 904L steel has such a high nickel content, it can cause people with nickel allergies to experience skin irritation. If you’ve got a bad nickel allergy, you might not want to wear a watch made from 904L steel.

304L stainless steel

316L might be the most common stainless steel alloy in watchmaking, but 304L is the most common stainless steel alloy produced in the world, full stop. It’s used to make everything from cutlery to spaceships, and is occasionally used in watchmaking as well – more commonly for internal components rather than watch cases. 304L steel is cheaper than 316L, but it’s more susceptible to corrosion.

Brands are unlikely to market the fact that a watch is made from 304L steel, and if they are, it’s nothing to be overly impressed by. Usually, only the very cheapest watches are made from 304L, such as generic designs or cloned designs you’d find on Alibaba and the like. Some aftermarket watch bracelets are also made from 304L steel. If you plan on swimming a lot with your watch, consider avoiding components made from 304L steel.

Submarine steel

Now we’re moving into niche stuff. A catch-all term for stainless steel alloys used in the construction of submarines, such as HY-80, XM19 or EN 1.3964, submarine steel alloys are typically designed to have incredibly high strength-to-weight ratios as well as high corrosion resistance. Some are designed to have anti-magnetic properties, too.

Part of the reason why this term is so vague is that, in some cases, the exact alloys are military secrets. For example, the “German Submarine Steel” Sinn uses for its U1 model is produced by ThyssenKrupp, and was developed in the late ’90s for use in the Type 212A submarine. However, neither Sinn nor ThyssenKrupp have revealed the exact composition of this alloy, only that it contains up to 18% nickel. In essence, submarine steel is a little bit of a marketing gimmick as submarine steel watches are not significantly better than 316L or 904L-cased watches. But it sounds very cool.

Lucent Steel A223

Lucent Steel is a proprietary Chopard stainless steel alloy that the maison claims to be 50% harder than other steel alloys. Its exact composition is a trade secret, but Chopard has revealed that it contains 80% recycled material. Significantly, it’s also lighter in colour and much shinier, giving it a highly reflective quality that easily catches the light across the watch’s contrasting brushed and polished surfaces. This means it likely has quite a high nickel content, although likely not as high as a 904L steel.

Ever-Brilliant Steel

Ever-Brilliant Steel is a proprietary Seiko alloy that the Japanese brand is increasingly using for Grand Seiko models. Seiko claims that it’s the world’s most corrosion-resistant steel, boasting a PREN (Pitting Resistance Equivalent Number, a standardised predictive measurement of a stainless steel alloy’s resistance to localised pitting corrosion) rating that is 1.7 times higher than that of stainless steel. It also features a brilliant white hue, which Seiko says is more noticeable along hairline finished portions of their watches’ cases and also explains that Ever-Brilliant Steel is more difficult to Zaratsu polish than other steel alloys.

Like Chopard, (Grand) Seiko has stayed fairly tight-lipped about the composition of Ever-Brilliant Steel, but it’s almost certainly a 904L steel. Side note: Seiko loves giving confusing names to their different proprietory alloys – they’ve got an alloy called “Brilliant Hard Titanium” as well as Ever-Brilliant Steel…

Everything else worth mentioning

While the focus of this article is the different grades or alloys of stainless steel used in watchmaking, there are also a few terms related to steel that I think are worth breaking down.

Surface treatments and case hardening

Stainless steel is already pretty tough, but some brands have developed surface hardening treatments that can make stainless steel even more scratch- or corrosion-resistant. Some of the most common are DLC (diamond-like carbon) and PVD (physical vapour deposition) coatings, which are thin films of material over the top of steel. These not only have an aesthetic benefit, making cases or bracelets appear uniformly black in the former’s case or coated in a thin layer of pigment or gold in the latter’s case but also make cases much more scratch-resistant. Some brands have also developed coatings that are transparent, such as Citizen’s Duratect and Seiko’s Diashield.

Other brands have invented and implemented case hardening processes to increase stainless steel’s durability. Rather than a coating, these processes chemically change stainless steel. Sinn’s Tegimented steel and Damasko’s ice-hardened steel are prime examples, both of which use low temperatures to diffuse carbon in the top few microns of a steel case, creating a more scratch-resistant gradual layer of material. The advantage of these case hardening processes is that they won’t peel off or degrade over time like a coating – however, they’re not impact-resistant, so big impacts will still dent them.

“Surgical grade” / “marine grade”

You might have seen “surgical grade” or “marine grade” steel used by watch brands to describe the steel in their timepieces. As we mentioned earlier in this article, 316L stainless steel is commonly used in marine and surgical applications. 304L steel is also frequently used for surgical applications. This is to say that “surgical steel” isn’t inherently superior to other stainless steel alloys used in watchmaking – indeed, it’s really describing the same thing. In that sense, describing a watch’s case or bracelet as being made from “surgical steel” is a bit of marketing fluff.

It’s worth pointing out that “marine grade” is a slightly less misleading term than “surgical grade” (as the former is an established synonym for 316L), but like the term “submarine steel”, it’s still a bit of a marketing buzzword, particularly if it’s used to describe watches that aren’t intended for professional diving.

“Recycled steel” / “eSteel”

Speaking about marketing, you might have also seen some brands tout the use of “recycled steel” in their watches. Ulysse Nardin, for instance, emphasises the use of recycled steel in the cases of their Diver collection, while Panerai has a range of “eSteel” watches that also use recycled steel.

While we applaud luxury watchmakers for taking a more sustainable approach to production, the reality is that steel is the most recycled material in the world and can be recycled basically indefinitely. For example, in Australia, 80-90% of all scrap steel gets reused or recycled, with similar rates for other developed countries.

Soft iron

While not a type of steel, soft iron is worth talking about as it’s a material that’s often utilised in watches: it’s a term you’ve probably heard before but you might not know what it means. For instance, many watches feature soft iron inner cages or dials, particularly anti-magnetic tool watches like the Rolex Milgauss or IWC Ingenieur.

“Soft” here actually refers to annealed iron. Annealing is a form of heat treatment where you heat a metal to a specific temperature and allow it to cool at a controlled rate, to increase its ductility and reduce its hardness – or, in layman’s terms, make it softer. Soft iron, unlike “hard iron”, has low coercivity – that is, it’s much harder to magnetise – so watchmakers use soft iron to shield watch movements from magnetic fields. This can take the form of soft iron dials, soft iron shielding around the watch movement (effectively a Faraday cage), or in conjunction with a double caseback, like in the Rolex Milgauss.