WHAT TWEAKS MY TOURB: Enough with the digital renders – brands need decent photography

Fergus NashOne of the most common tips given to watch shoppers is to go and see their potential purchases in the metal before buying them. Not only is it beneficial to feel how they fit on your wrist, but also how they interact with real-world lighting and real-life eyeballs. In the online age, and especially post-COVID, visiting a store is not often practical or even possible. The next step is to find photos and maybe videos of the watches, as you can still get a pretty good idea of how they look in physical space. The only visual aid which has next to no redeeming factors is a digital render.

The improvement in technology over the last two decades has been incredible to witness, especially in the realm of 3D modelling and rapid prototyping. All you need to do is look at the quality of CGI in movies to see how far we’ve come, and similar progress has been made with the ability to build a 3D model in software, and export either digital renders or send it to a 3D printer. For businesses who manufacture physical products, the time between conceptualisation and prototyping has shrunk exponentially, saving a tremendous amount of time and money. While the digital renders are certainly a technical improvement from hand-drawings and a much more reliable reference for the company, they really have no place in a consumer-facing context.

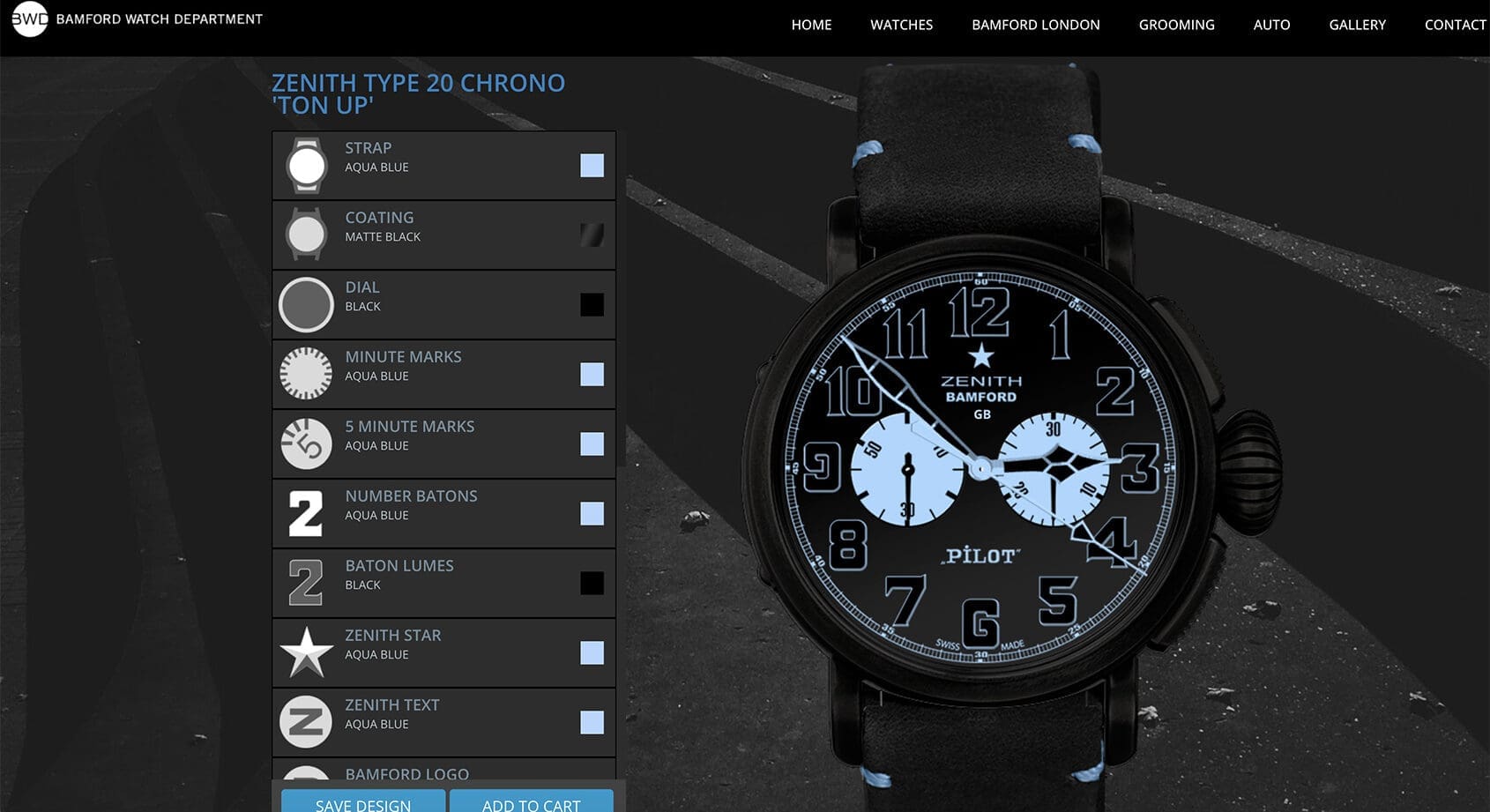

Just as prototyping technology has improved, so has accessibility to great product photography. Small businesses can now get perfect photos of their merchandise with just a cheap light box or tent, LED lighting, and a smartphone camera. If the DIY approach is that easy, what’s stopping the big brands from prioritising photography on their product pages? Even if they have great product photos with artful composition and interesting backgrounds, often the digital renders are shown as the default image. This completely removes the charm from any watch, and makes them look dull and lifeless no matter how high the quality is. Just as renders of human faces can enter the “uncanny valley” where they become unsettling, we need to see how specific reflections are cast off polished surfaces instead of just grey amorphous blobs representing stainless steel.

Given my profession as a Time+Tide writer, I tend to see a lot of press releases and sometimes write “Introducing” pieces off the back of them, before the opportunity for a “Hands On” review pops up. It’s clear that companies have time constraints when developing new watches, and sometimes the descriptions are being written by copywriters before a physical prototype even exists. In order to get around this, they can sometimes use vague language to cover all bases just in case something changes along the way. The problem with that is that sometimes the digital render of the watch is too vague to see specific details, such as the texture of a dial, whether hour markers are applied or printed, what material a bezel insert may be, and much more. Without naming names, I’ve even received a press release from a major Swiss brand that claimed a watch was going to have a sunburst finish only for the watch to be later released with a completely matte dial, making that section of my review incorrect. Comparing the digital render to the finished product of that watch could be mistaken for two completely different watches, especially because it’s an established design where dial colours and textures are often the only difference between references.

Considering that watch enthusiasts generally obsess over minuscule details, it seems odd that companies rely upon images which are so lacking in detail, fidelity and life. Especially in the case of watches that are actually brilliant, a digital render is unhelpful at best and unflattering at worst. Although digital renders serve a useful purpose, they should never take the place of professional product photography.