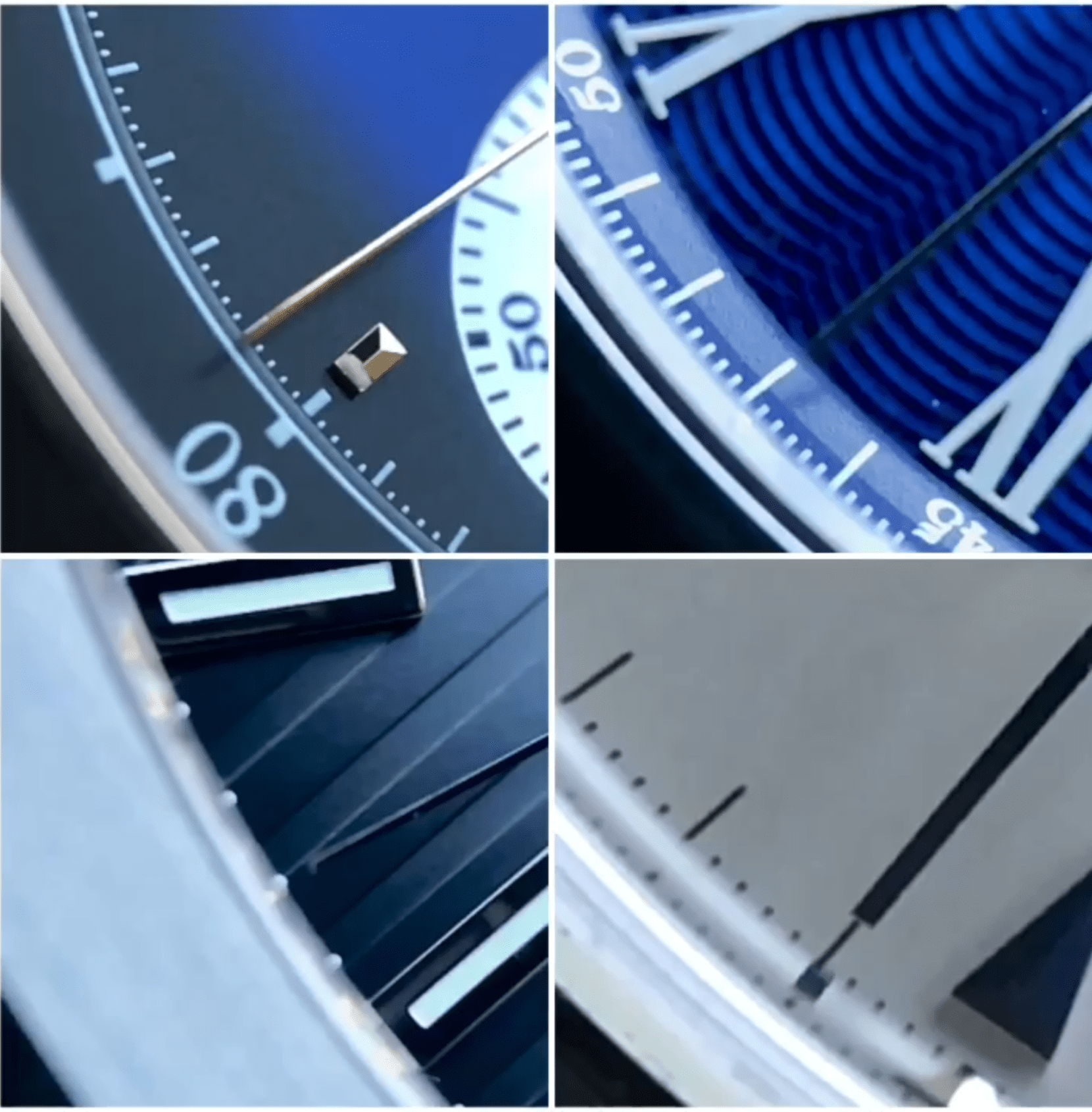

Watch four different vibrations per hour (VPH) in slo-mo, care of the macro maestro @horomariobro

Zach BlassWatchmaking is a game of microns and millimetres. The movements powering wristwatches are effectively a tiny city of gears and levers, that when blown up to a larger scale, become a chronometric Atlantis waiting to be explored and appreciated. One of the first things people notice when looking at a dial of a watch is whether or not it has a sweeping seconds hands. But as enthusiasts and collectors are aware, not all sweeping hands beat to the same drum. To the naked eye, the differences can be hard to detect, but thanks to the maestro of macro, @horomaribro, today we take a closer look at wristwatch VPH, or vibrations per hour, and what it means for a watch’s aesthetic and performance.

Andrew McUtchen: Okay, this is your classic VPH comparison. Tell me about your intention behind this one.

@Horomariobro: So here I was just trying to show the various “heartbeat rates” of different watches. Each has its own array of beating, and I’m trying to show how many ticks there are between second hashes. Normally, people would talk about how many beats per hour and stuff like that. With my macro video, I’m trying to convey, “Okay, from the number of the ticks, you can also figure out how many beats per hour.” There’s the 18,000, 21,600, 28,800 and 36,000.

https://www.instagram.com/p/CGmt2JfhBNF/?utm_source=ig_web_button_share_sheet

Andrew McUtchen: When you look at a watch with your naked eye, can you tell the VPH?

@Horomariobro: Oh … I cannot. It’s too fast. Using a loupe or macro lens and slow motion makes it easier.

Andrew McUtchen: But you can kind of tell, right? You can tell a 36 versus an 18? I think I can.

@Horomariobro: Yeah. If form is smooth, but it’s hard to differentiate 28.8 and 36; I probably still cannot. 28,800 vph is eight beats per second versus 10. It’s very close, but then 18,000 is half the rate of 36,000, which makes for an easier distinction … but my eyes are not that good. I need macro shots to help me.

Andrew McUtchen: Is it a case of “the more vibrations, the better”? Is it that simple?

@Horomariobro: I don’t know if it’s more vibrations the better. I’m not a watchmaker, but, in terms of accuracy, the more vibrations the easier it is to maintain accuracy within a watch – but the tradeoff is more or faster wear on the parts/components. I think more vibrations per hour also helps for more accurate measurements. In regard to a chronograph, it helps you measure time to a greater degree, because with 36,000 VPH, for example, you can measure a tenth of a second due to the 10 ticks per second elapsed.

Andrew McUtchen: Do you have any other comments on this video?

@Horomariobro: One final takeaway is simply that the higher the beat, the smoother your hand sweeps. Your second hand will move with less stutter when you see it with your naked eye, which is a good reason to seek higher VPH.

Andrew McUtchen: And you asked people to guess the models too: what were the four again? Just so that we’re clear.

@Horomariobro: Yeah, so the first one at 18,000 is Datograph — the Lange Datograph. Okay, and the blue dial right next to it is a Seiko Presage. The blue one right below the Datograph, that is the Nautilus. The last one is the Zenith.

Andrew McUtchen: Yeah, I saw people struggled a bit with the Zenith…

@Horomariobro: Yeah, the only tell there was the high-beat movement. Some models, such as the Nautilus, were easier to spot due to the iconic nature of their dials.