Space odyssey: How the Omega Calibre 321 became the first watch movement on the moon

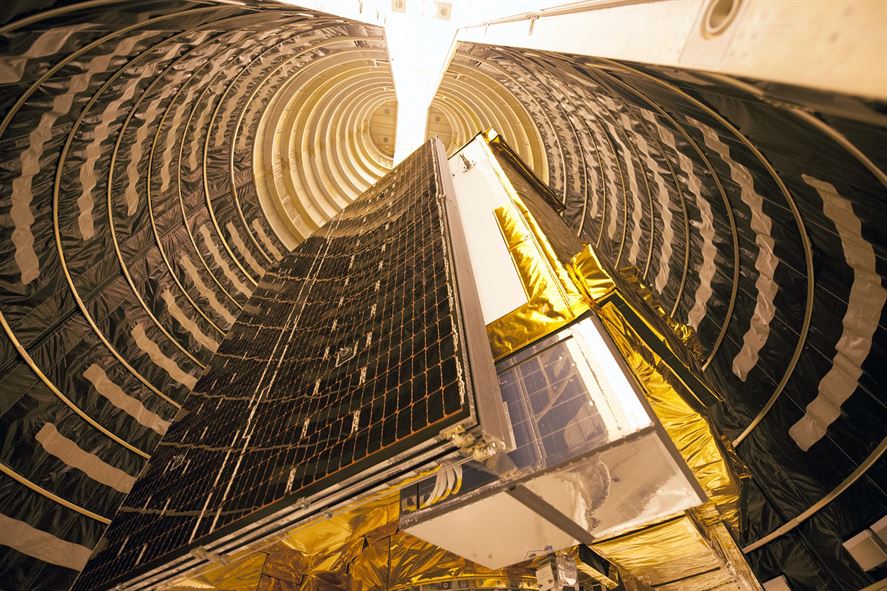

Brendan CunninghamIn many ways, outer space and space exploration have become a routine part of life. We all carry a device that listens to signals from space in the form of our mobile phone. Most can receive messages from GPS satellites in medium earth orbit more than 20,000km away. Just as space is now entwined with our lives, so is timekeeping inseparable from space.

GPS relies upon clocks. A satellite sends a signal that says “I sent this at time X.” Your phone provides the time, Y, when the signal was received. The elapsed time between sending and receiving (Y minus X seconds) when combined with the known speed of the signal (Z km/s, from physics) reveals your distance from the satellite ( (Y-X)*Z). If your distance from three satellites is determined, your location can be trilateralated. The three distances are the diameter of three unique circles, each with a GPS satellite at its centre. Those three circles intersect at only one point and that point is your location.

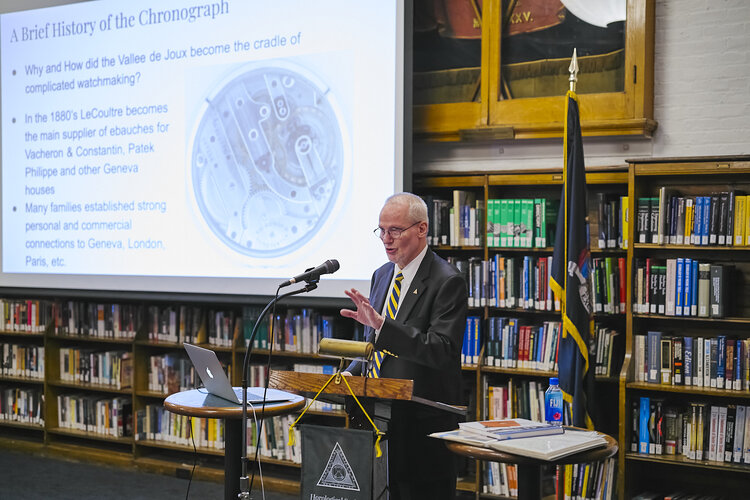

What is truly remarkable about timekeeping and outer space is that when astronauts are in this treacherous vacuum they typically employ a mechanical device to mark the time. No circuitry, no battery, no LCD, just those precisely lathed gears pushed by the energy of a spring. And there was only one mechanism that first earned certification for extra vehicular activity in outer space: the Omega Calibre 321, a movement that powered the Omega Speedmaster Professional soon after its introduction to the world. Armed with a passing familiarity with this history, I recently attended a standing-room only lecture delivered by watchmaker Bernhard Stoeber at the Horological Society of New York to learn more about this remarkable piece of Swiss technology.

Mr Stoeber is a fourth-generation watchmaker and for 11 years he was employed by Omega in a senior watchmaking position. In the 1980s he worked out of New York City and personally serviced Omega Speedmasters flown to space on NASA missions. The service was completed annually under a contract NASA and Omega signed more than 10 years earlier. It is fair to say that Mr Stoeber is one of the world’s top experts when it comes to the Speedmaster and the reference 321, he even possesses copies of the original technical drawings of the calibre, which he has shared with those learning to service it today.

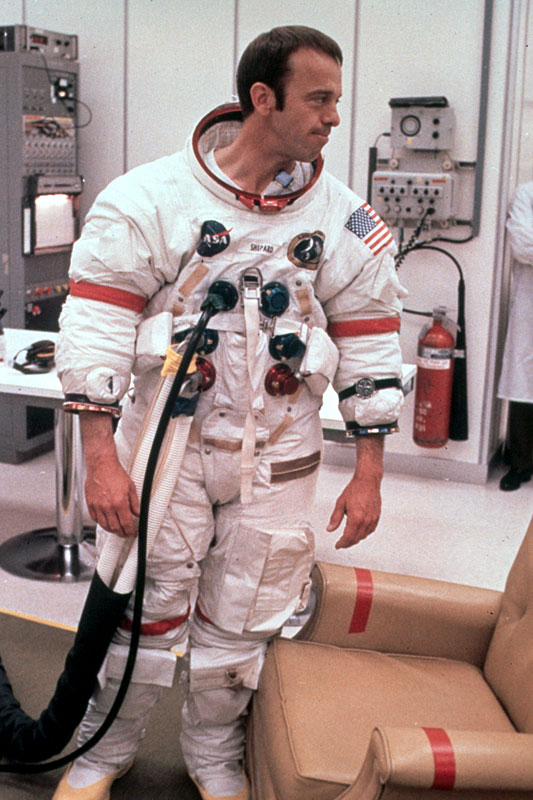

You might be inclined to believe that this movement was cleverly numbered in reference to the final moments of a rocket launch countdown: “3 … 2 … 1 … liftoff!” But, in reality, this calibre was numbered by Omega in 1946, 18 years before astronaut Wally Schirra brought the 321 into space during the Mercury-Atlas 8, Sigma 7, orbital mission. Schirra’s paternal grandparents were from Switzerland and Bavaria which, in part, might explain why he owned an Omega Speedmaster. Schirra brought his own personal watch on his first space flight and two other astronauts subsequently did likewise with their own Speedmasters (Stafford and Gordon in 1965 and 1967, respectively).

Mr Stoeber also explained that the 321 was actually the product of another company: Lemania. Omega, Tissot and Lemania were connected through the Société Suisse pour l’Industrie Horlogère (SSIH) holding company. In 1940, Omega tasked Lemania with creating a 27mm chronograph movement offering two sub-dials tracking elapsed time. The project fell to Albert Piguet who, with two colleagues, developed the Lemania CH27. This movement was sold by Omega as the calibre 320. It lacked interchangeable parts as well as an hour counter.

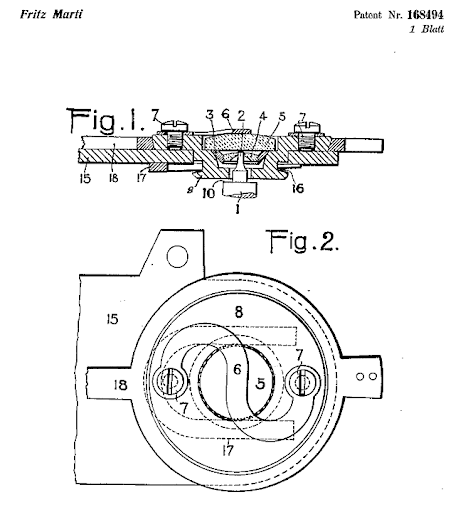

One of the most important improvements associated with the next calibre in the line, the 321, was the introduction of Incabloc shock absorption in order to protect the balance wheel. As we’ll soon see, when it came to a spaceflight-certified wristwatch, NASA was rightfully concerned with the stresses associated with “Delta-v”, that is, the intense forces unleashed by acceleration and deceleration as the watch, and astronauts, entered and exited Earth’s atmosphere. Improving the calibre 320 through the addition of shock absorption was critical for acceptance of the movement by NASA.

In 1968, Omega introduced the calibre 861 and, much to the chagrin of Speedmaster collectors, stopped production of the 321. The 861’s most noteworthy update to the 321 was the interchangeability of parts. When asked which movement he preferred, Mr Stoeber noted that, as a watchmaker, the 321 was more desirable because it required careful adjustment in order to achieve manufacturer benchmarks. In particular, 321 movements were customised with a watchmaker’s “bespoke” adjustment to the flyback hammers (these reset the chronograph to zero). Each 321 was, therefore, different from all the others. It bore the mark of a watchmaker’s careful assessment and fine tuning. In contrast, the 861 replaced the 321’s column wheel with a set of cams. This, in combination with the interchangeability of parts, meant that the movements were more uniform and less tailored.

Speedmaster aficionados generally concur with Mr Stoeber in their preference for the 321 movement. No doubt this has to do with the fact that, in 1965, this calibre was the only mechanism to pass NASA’s brutal testing regimen. Candidate watches submitted by Rolex, Longines and Hamilton did not make the grade. To the best of Mr Stoeber’s knowledge, not even Omega’s own calibre 861 passed NASA’s testing. The 321 survived six 40G shocks coming from six different directions. This is more than 5.5 times the maximum number of Gs that NASA observed during re-entry of the Apollo 7 through 17 missions, a very decent margin of error. The Speedmaster crystal did not build condensation over ten 24-hour cycles in greater than 95 per cent humidity with temperatures ranging from 25° C to 70° C. In Mr Stoeber’s estimation, almost all other timepieces would fail this test. The remaining NASA tests are equally impressive.

As watch collectors, we are fortunate to witness the return of the 321 to Omega’s line-up as of 2019. Last summer, the Speedmaster Moonwatch Professional 321 was released in platinum for just above $AUD 86,000 ($US 56,400). There is already a waiting list. And the morning after Mr Stoeber’s lecture, to great fanfare, Omega announced a steel version of the Speedmaster Professional with a slightly modified 321 movement priced at approximately AUD $20,500 ($US 14,100). See Time+Tide’s coverage here.

Many observers question whether this five-figure price tag is reasonable. Some are referring to it as “peak steel”. But, as noted by the esteemed team behind IG account horology_ancienne, it is the elite watchmakers in Omega’s Atelier Tourbillon department who will follow a bygone form of manufacturing when it comes to these timepieces, assembling the movement, encasing it, and attaching the bracelet. Each watch will have been “born” by a single watchmaker. Under more common “assembly line” production, a watchmaker performs a narrowly defined set of tasks as watches are handed off from one to another. Departure from assembly line manufacturing is, in no small part, responsible for the price we’re witnessing, since the assembly line is a more efficient process.

For potential buyers it is helpful to understand that because of careful adjustment to non-interchangeable parts (conducted by highly experienced watchmakers), the 321 was able to survive NASA’s testing. Today, Omega offers a timepiece whose durability and performance are similarly achieved through the efforts of a craftsperson with decades of experience. The 2020 release of the Speedmaster 321 represents a certain artisanship in assembly that is typically associated with independent brands. However, with this watch, it is combined with the staying power of one of the largest manufactures in Switzerland. This gives a different perspective on the offering, one which collectors will undoubtedly find appealing.

The Horological Society of New York is offering watchmaking classes at The Hourglass in Melbourne, Australia Feb 29 and March 1. You can obtain tickets here. Brendan offers an economic analysis of horology at Horolonomics.