IN-DEPTH: The history of Bovet, a contemporary brand with impeccable old-world credentials

Fergus NashDespite the age of the watchmaking trade, there aren’t too many brands that can boast 200 years of history. Those that do often have insular development, still operating from within their small town beginnings and sometimes run by the original family. The story of Bovet is much more diverse, including a multitude of characters and cultures all culminating in a contemporary brand with old-world ties. Their new watches are eccentric and inventive in the most delightful way, now let’s go back to find out where it all began.

There isn’t a tremendous amount known about the earliest member of the Bovet family, but love of Fleurier in the Swiss Canton of Neuchâtel certainly ran in their blood. The earliest records trace the Bovet lineage back to Antoine Bovet, born in Fleurier in approximately 1480. At around the 1660s, it becomes clear that the Bovet family predominantly worked in stone masonry, before Jean-Jaques Bovet started to deviate as a stone or gem polisher in the mid 1700s. His son, Jean-Frédéric Bovet, was the first watchmaker in the family as the profession exploded throughout the region. By 1794, about 13% of the Fleurier population were employed as watchmakers.

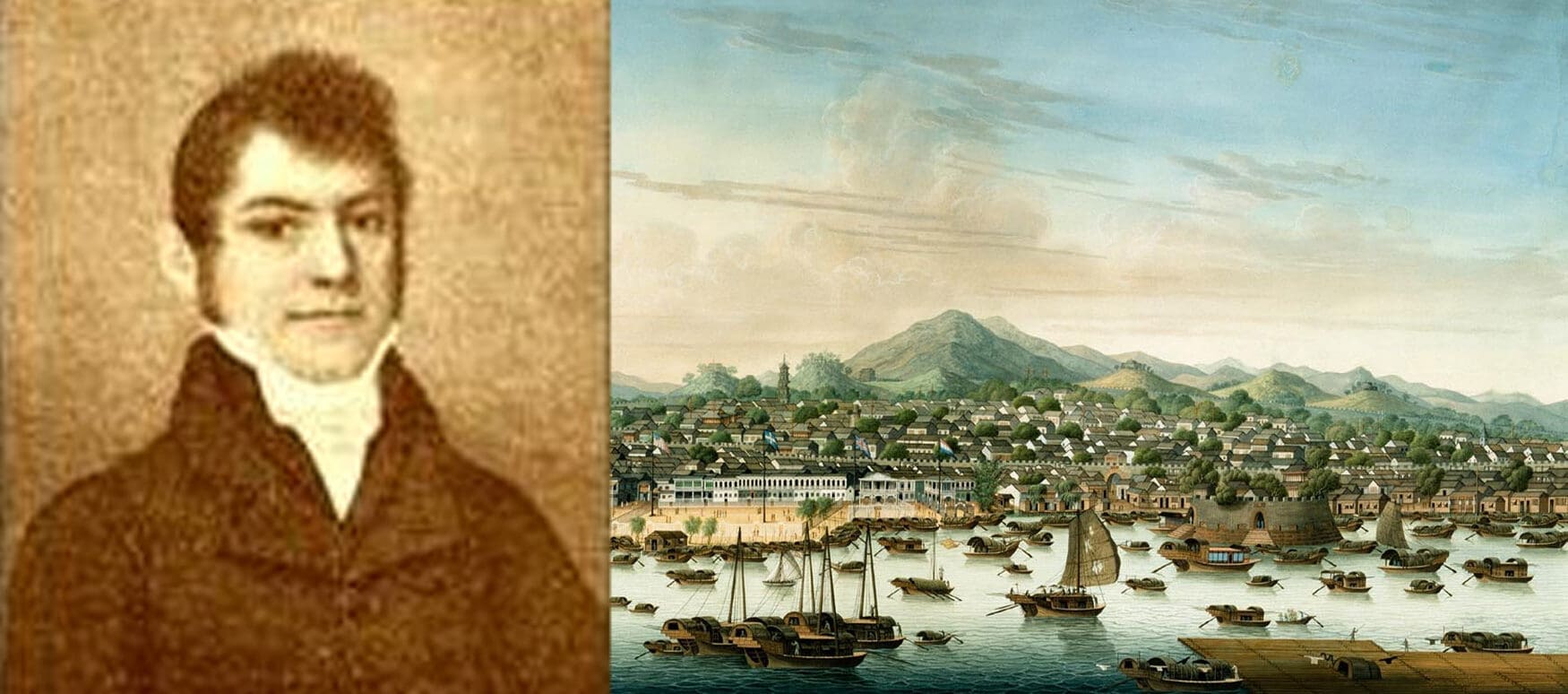

The story of Bovet as a brand begins around 1814, when three of Jean-Frédéric sons moved to London after completing their watchmaking apprenticeships. The young Edouard Bovet became employed by a company called Magniac & Co., run by Charles and Hollingworth Magniac. Although the East India Company still held a monopoly over trade with India and the Far East, some shrewd businessmen had discovered a loophole. Taking out Prussian citizenship, the Magniac brothers became Chinese consuls of the King of Prussia, giving them diplomatic residents rights to trade with China without a license. At the time of the Qing Dynasty, the port of Canton (modern-day Guangzhou) was used to control trade with the West, and so that is where Edouard Bovet was sent to repair watches in 1818.

Having a Swiss watchmaker stationed in Canton to work on imported Swiss watches was an incredibly successful business model, and in 1822 the Bovet brothers founded a general partnership with Edouard in China, Alphonse and Frédéric in England, and the youngest Henri back in Fleurier. Jean-Frédéric had passed away in 1818, but the watchmaking business was operating at peak quality. Often decorated with pearls and enamel paintings, the Bovet watches were also slightly more affordable than some of the Swiss counterparts that were reserved for royalty and aristocrats, allowing them to become a household name. For the Chinese population, the word ‘Bovet’ became inseparable from any high-end watch, and their watches were eagerly accepted as currency by most merchants. Many Bovet pocket watches sported glass baseback windows so that you could see the intricate movement decoration, and a specialty of their calibers was a 1Hz tick similar to modern quartz watches.

Edouard Bovet lived large in Canton as his wealth grew, and he had a son named Georges in 1826 although the mother died in childbirth. Things back home in Fleurier were also still complex. During the Napoleonic Wars, Neuchâtel was a heavily contested region. Although the 1815 Congress of Vienna re-established Swiss independence, the Liberation Wars of 1813 had restored rule of the Principality of Neuchâtel to the Kingdom of Prussia. Ironically, even though it was the deal between the Magniacs and Frederick William III that allowed Edouard Bovet to go to China in the first place, the Prussian control of Neuchâtel was one of the main reasons the Bovet brothers had moved to London back in 1814. When Edouard returned home to Fleurier with his son in 1830, the Principality of Neuchâtel was still the only member of the Swiss Confederation that wasn’t a republic. There was a small and unsuccessful revolution in December of 1831, where Edouard and many other Republican watchmakers were then exiled to the French border city of Besançon.

Despite the personal setbacks, the Bovet family had bred like rabbits and all of Edouard’s brothers and nephews ensured that the company kept up its success in all corners of Fluerier, London, and Canton. The brand re-registered as Bovet Frères et Cie. in 1840, and in 1848 the Principality finally had a successful revolt against the Prussians. Edouard returned home once again to his Fleurier home they nicknamed the China Palace with a new wife, but he unfortunately died in October 1849 at the age of 52. Business continued to boom, although there was less and less motivation to focus on watchmaking. The Bovet family with its many generations of trade with China were lured away from watches and tempted to pursue other trade avenues, as complications from the Opium Wars, competition from France and America, and a growing counterfeit industry all contributed to a downturn in interest. In 1864, they sold the company to their manufacturing inspectors.

With Bovet watch production turning into drip-fed contracts operation, the company fell down a ladder of cascading buyouts. It was purchased by the Landry Frères in 1888, Cesar and Charles Leuba in 1901, Jacques Ullmann and Co. in 1918, and even returned to the Bovet family via Albert and Jean Bovet in 1932. The pair were already successful watchmakers in their own right with several chronograph patents including the mono rattrapante, but Favre-Leuba bought the company and facilities again in 1948. After nearly 100 years of swapping hands and stagnation, Favre-Leuba stopped producing Bovet-branded watches and just used the facilities for their own means. The brand got passed off again in 1966 to a Swiss watchmaking cooperative, and it seemed as though Bovet’s only legacy was Edouard’s China Palace, being used as the Fleurier Town Hall from 1905.

Nothing happened until 1989, when the Bovet trademark was briefly owned by Parmigiani Fleurier, but it was quickly sold on again to investors in 1990. The name got updated to a more contemporary Bovet Fleurier SA, but again it sat dormant until being acquired by entrepreneurs in 1994. Roger Guye and Thierry Ouelevay opened a new office and began producing watches again, with fewer than 1,000 pieces produced annually and specialising in elaborately decorated wristwatches. The dawn of the 21st century saw yet another change of hands in 2001, bought by Pascal Raffy who had a distinct vision for the brand. He made a series of purchases throughout the mid-2000s to establish a strong base of in-house production, including various factories and the historic Château de Môtiers.

Dedicating the business to the original founders and forming a promise to honour its former glory, the company was renamed again to Bovet 1822. With an emphasis on unique models and limited production, the new generation of Bovet watches take a lot of inspiration from the sheer extravagance of their old pocket watches. There is a wealth of new and exciting designs and patents, and it would be easy to imagine the first lovers of Bovet watches in the 19th century still falling in love with their watches today. It’s also returned to being a family business, with Pascal Raffy’s daughter Audrey joining the company as Vice President in 2020.