How Junghans went from making straw hats to become a global power

Fergus NashThe name Junghans is familiar to a lot of watch enthusiasts, even if you’re not totally aware of the brand’s former or current glory. They’re currently best known for their German-made watches with Bauhaus elements from the legendary designer Max Bill, although at one point in the early 20th century Junghans was the biggest clock manufacturer in the world. Given that this year marks the founder Erhard Junghans’ 200th birthday, it seems high time that the incredible story of his brand’s history was made common knowledge.

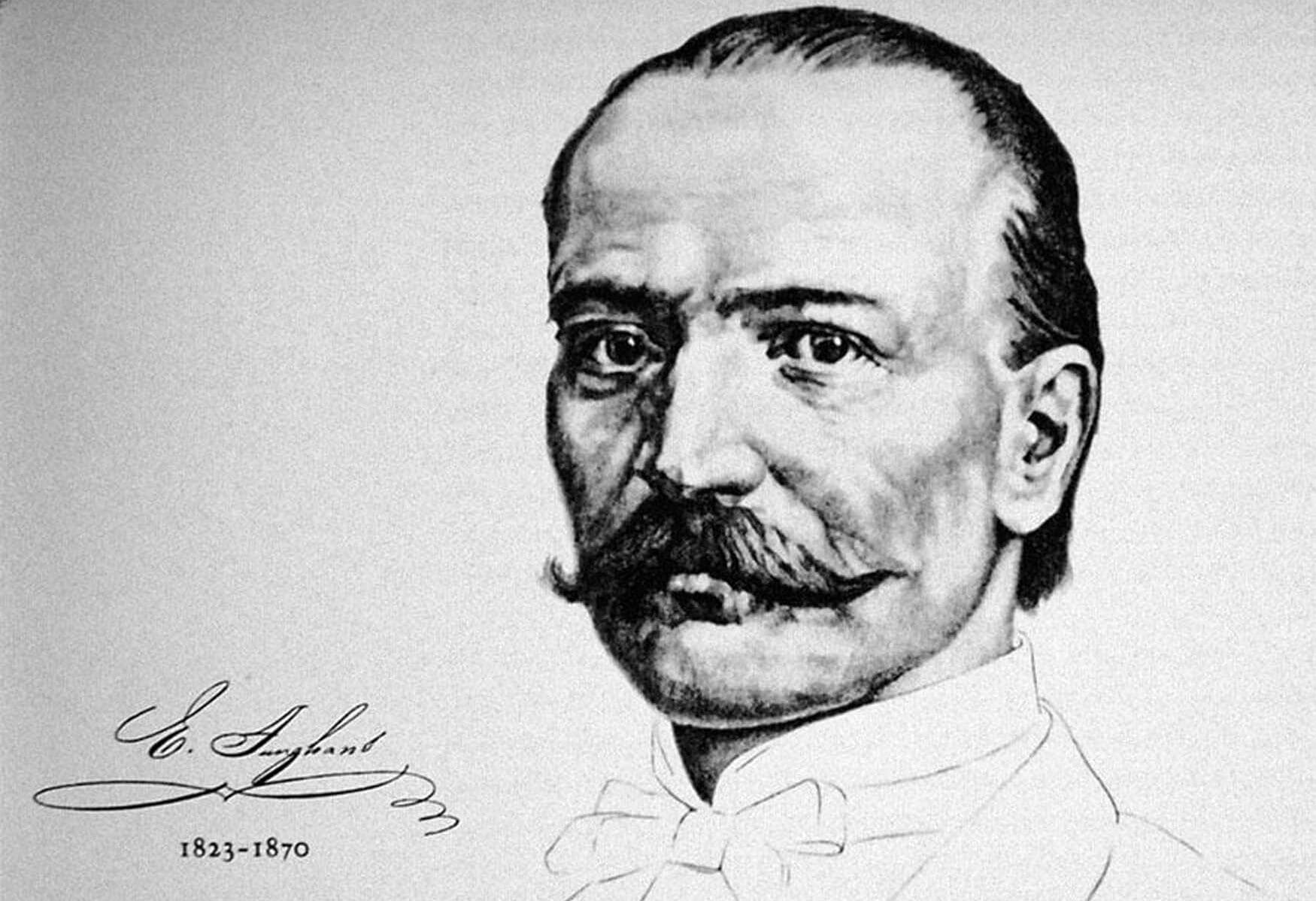

Erhard Junghans was born on January 1, 1823 to his mother Barbara and his father Nikolaus, who worked in knitting and intaglio printmaking. The family moved from Horb am Neckar in Germany to the Black Forest town of Schramberg in 1841, as the industrial revolution was expanding into smaller towns. While Nikolaus Junghans took a job at the earthenware factory Uechtritz & Faist, the 18-year old Erhard embarked on a two-year apprenticeship at the local straw factory, making hats. He continued to work at the factory making straw hats as well as travelling back and forth to Switzerland and France to improve his linguistic skills, which was clearly impressive to his boss’ daughter Louise Tobler. Erhard Junghans married Louise in 1845 and they went on to have eight children, although their last son would tragically die at the age of two in 1860.

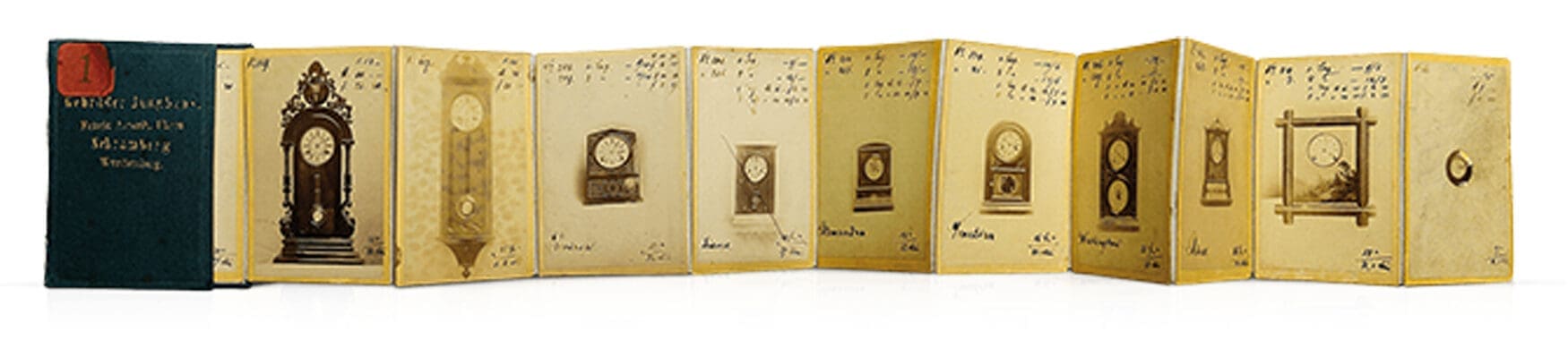

Erhard’s father-in-law and the owner of the straw factory died in 1854, and Junghans was promoted to partner and managing director. Although he was successful in his role, he was denied a pay rise and decided to quit the company, taking on a new venture with his brother-in-law Jakob Zeller-Tobler. The pair decided to open up an oil mill in 1959, however the business was a fast failure. Undeterred, they pivoted into creating watch components after it was suggested by Ferdinant von Steinbeis, a powerful politician and advocate for industrialisation. Aided by Erhard’s brother Xaver, who had emigrated to the USA as a carpenter back in 1847, the Junghans company was built from the ground up with American business practices throughout the 1860s, and Jakob Zeller-Tobler departed. Despite having had no experience with watchmaking, Erhard Junghans managed to set up what would become a global powerhouse.

Although we think of the incredible advancements during the industrial revolution as a close step to modern living, unfortunately there was still a lot left to be desired in medical fields. In the Autumn of 1870, Erhard Junghans died of a sore throat at only 47 years old. He left clear wishes that the Junghans watch factory be handed over to his three surviving sons — Erhard II, Arthur, and Georg.

While the widow Louise managed the company between 1870-1875, the life of young Arthur Junghans was unfolding like a bizarre espionage film. He had completed a watchmaking apprenticeship and gone to trade school in Stuttgart, but was actually fighting as a volunteer officer in the Franco-Prussian War when he heard news of his father’s death. He returned to Schramberg for a time, but was ordered by his mother to follow in his uncle Xaver’s footsteps. Travelling to America and taking a false name, Arthur Junghans worked in factories assuming any role he could from cleaner, blacksmith, lithographer and more to study the American methods. He came back to the family business in late 1873, and much to the dismay of the workforce, began to implement changes.

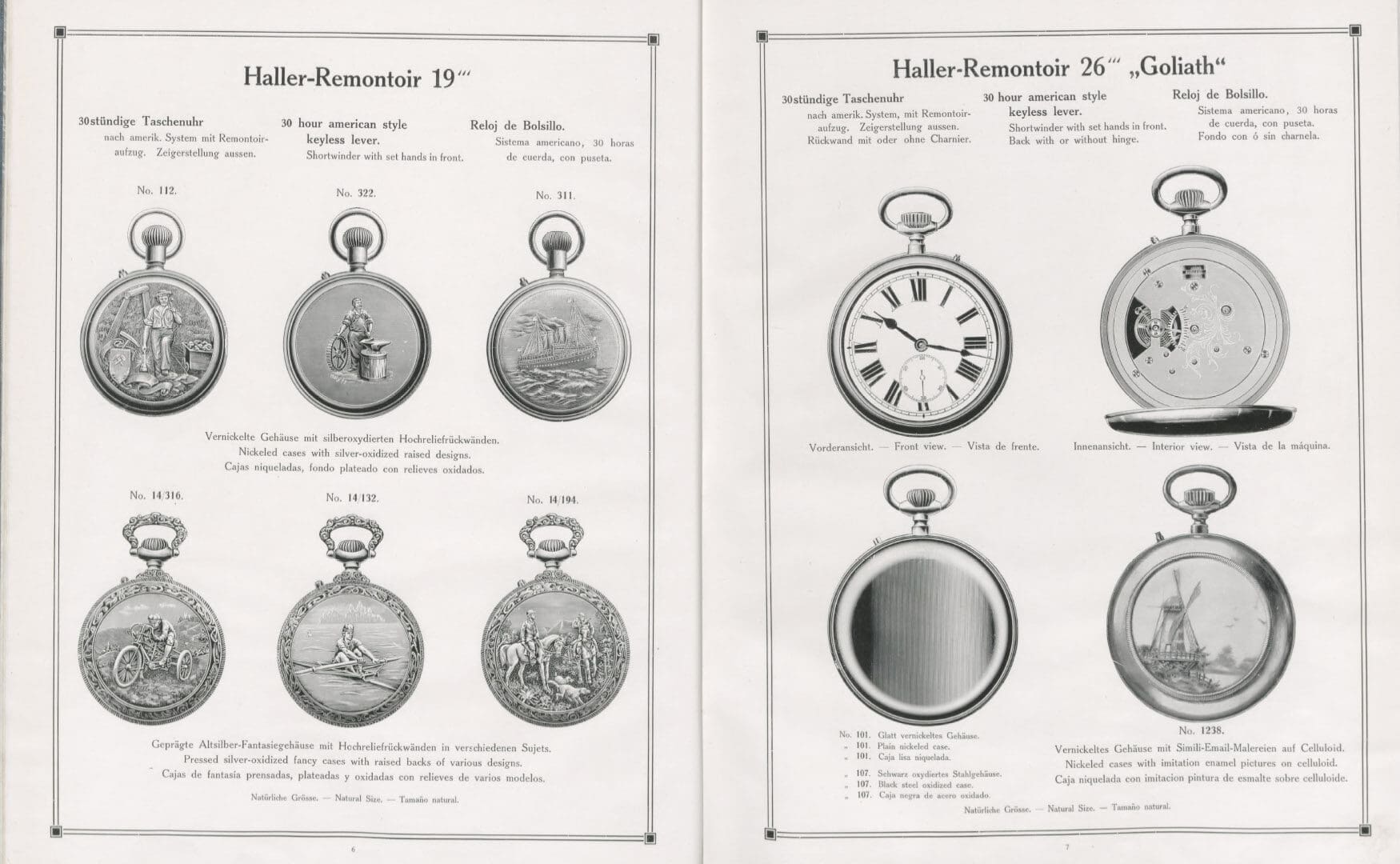

The American capitalistic efficiency brought the Junghans company successful results, and Louise handed over control to her sons as per Erhard’s wishes. Erhard II took charge of the business and technical management side of things, while Arthur handled the rest. There wasn’t a place for Georg as he was only 14 years old, but he would later become Technical Director at Siemens & Halske — now the largest industrial manufacturing company in Europe worth nearly €120 billion. After years of producing all sorts of clocks and components with rampant success, Junghans attempted to make their own pocket watches with several attempts between 1883 and 1894. These humbling failures led them to make yet another very American “if you can’t beat them, buy them” business decision, merging with the experienced Thomas Haller company in 1900.

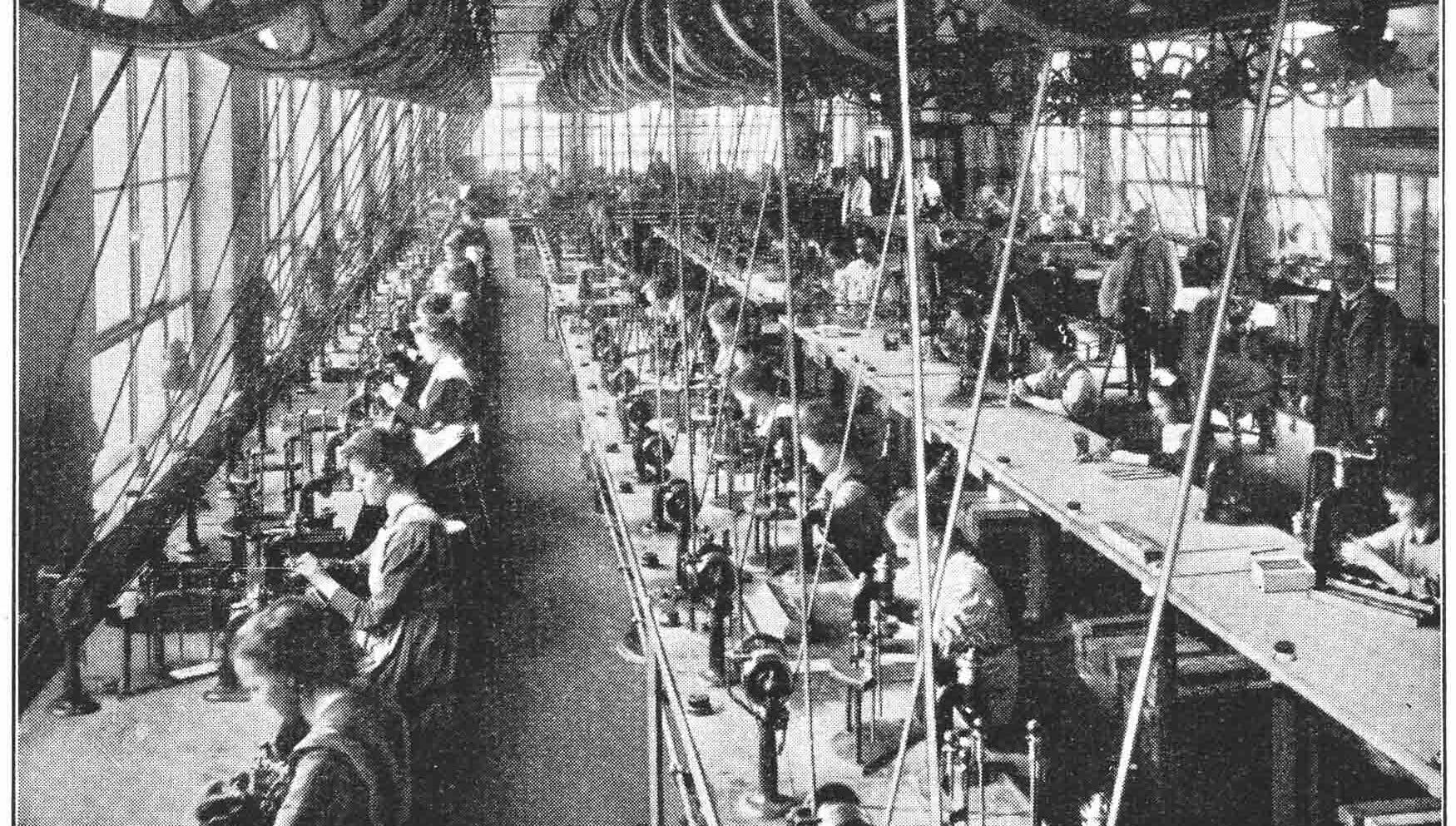

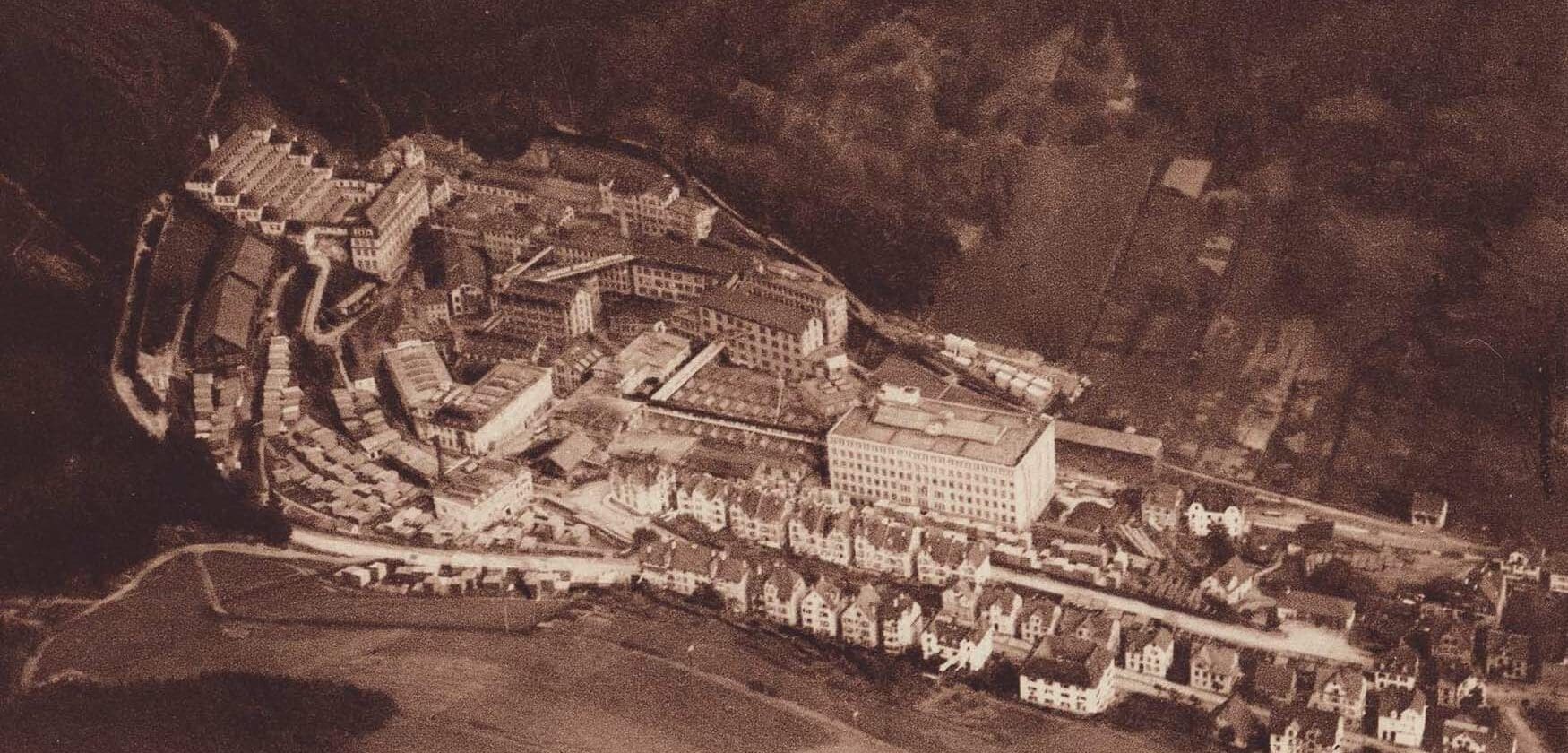

By 1903, the 3,000 employees in Junghans’ Schramberg factory made them the world’s largest watch manufacturer with an annual production of three million watches. Erhard II had left the company in 1897, but Arthur was still very much a passionate force. Arthur Junghans also managed to become a significant figure in the automotive world, as he was close friends with Gottlieb Daimler and Wilhem Maybach. While taking a drive in a Daimler prototype, Maybach’s clothes caught fire from a defective fuel line and Arthur saved him by throwing him into nearby water. He then suggested the invention of electric ignition to Daimler, and also invented worm gear steering so they could use a steering wheel instead of awkward levers.

Arthur Junghans’ control of the company continued to see success through the First World War, including being an early adopter of luminous paint on the hands of pocket watches and alarm clocks in 1912. They were also manufacturing ammunition fuses as early as 1906, however he passed away in 1920 aged 68, leaving his own sons Erwin and Oskar in charge. The rise of the wristwatch boosted Junghans in 1928, with the company initially buying in movements before going entirely in-house from 1930.

World War II was a dark time for all. As 1933 saw the seizure of power by the Nazi Party, thousands of factories across the country were turned towards war efforts. Having already produced a mass quantity of fuses, Erwin Junghans as General Director received armament orders to continue making a variety of fuses as well as precision clocks for aircraft and ships. Their employee base in Schramberg alone had grown in excess of 9,000, and the old factory primarily churned out explosive detonators. Towards the end of the war, the factory became housing for 862 prisoners of war and forced labourers. When the war ended, much of the machinery was dismantled and taken to France, and production of watches was resumed in 1946. Even then, Junghans was forced to send blank movements to French manufacturers for export under their names.

Perhaps overcompensating for the damage of their German reputation, Junghans spent the late ‘40s and early ‘50s focusing only on high-quality watches, and they quickly became one of the largest chronometer manufacturers in the world. Sadly, the Junghans family were removed from the company during a hostile takeover by Diehl in 1956, separating the watchmaking and fuse businesses further. Diehl still own JUNGHANS Defence today, making artillery fuses with the same eight-pointed star logo that has been in use since 1890. One positive of 1956 however was the enlisting of Swiss artist Max Bill, who designed the popular Junghans teardrop kitchen clock with its famous Bauhaus style. He continued to work with the brand through the 1960s, imbuing that minimalist and communicative perfection into a variety of gorgeous wristwatches.

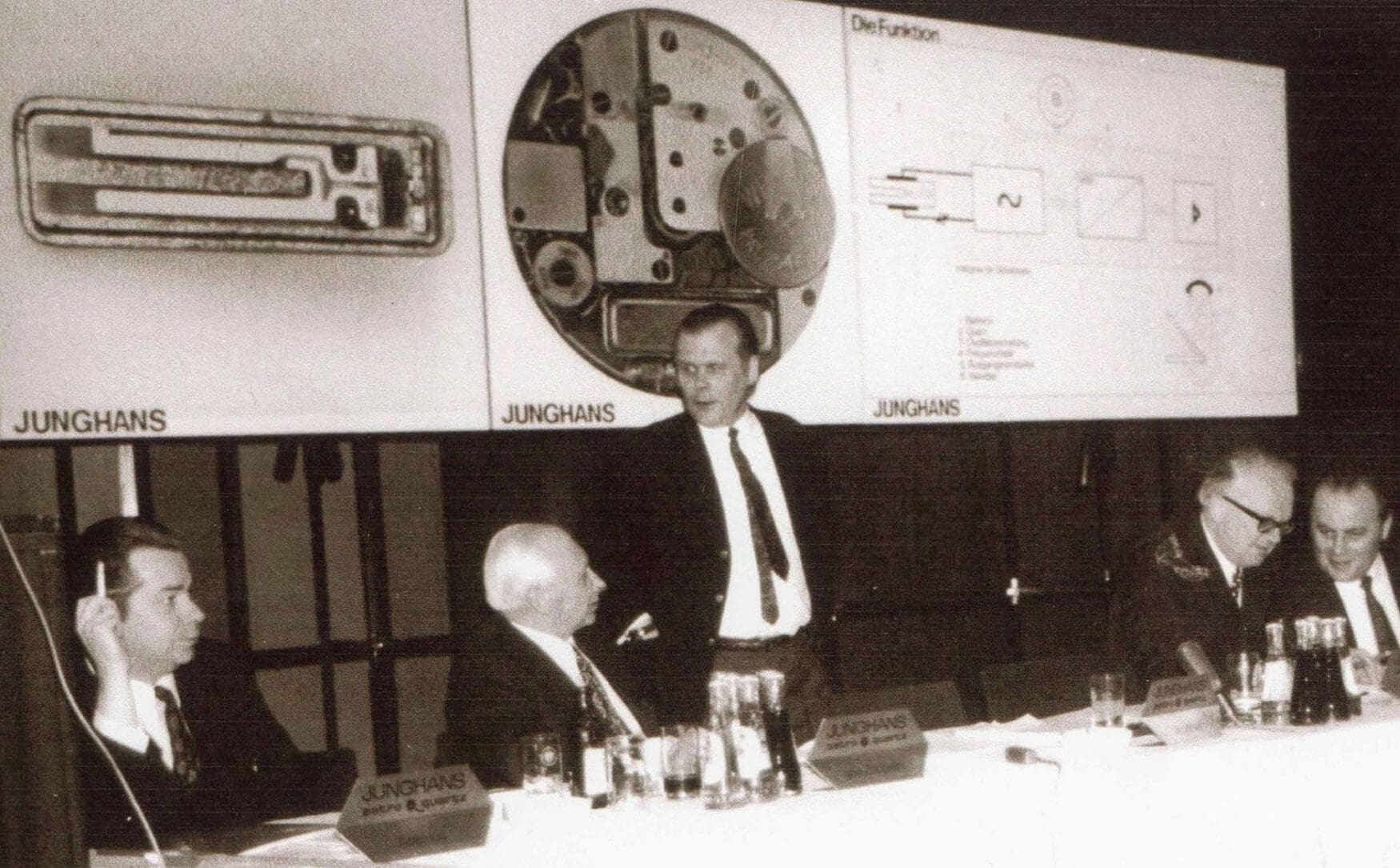

Junghans’ survival in the latter half of the 20th century was truly admirable considering the hardships that all watchmakers faced, both from the rise of Swiss sports watches from the likes of Rolex and the Quartz Crisis threatening mechanical watchmaking on a global scale. Junghans released the first German quartz watch in 1971 and was the official timekeeper for the 1972 Munich Olympics, however they had to suspend mechanical watch production in 1976 for a time. They pioneered radio control in the ‘90s, presenting the Junghans Mega as the first radio-controlled wristwatch in 1991, however the company was struggling. When the Diehl Group finally relinquished the watch division of Junghans GmbH, they had only 220 employees. They were sold to a holdings company in 2000, and were forced to file for insolvency during the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, when employees had dwindled to 115. Thankfully, Schramberg locals Hans-Jochem and Hannes Steim took over the company in 2009 and achieved instant sales growth.

Since then, the return of a father and son ownership has benefitted Junghans greatly. They hit their 150th anniversary in 2011, and have continuously rebuilt their reputation across both affordable and luxury models. In 2018, the Junghans Terrassenbau Museum was opened to celebrate Black Forest clock and watch history across nine floors. So whether you’re looking to pick up an affordable and versatile watch like the Max Bill, or even an adrenaline-fulled retro chronograph like the Junghans 1972, you can now appreciate just how deep their story goes.