HISTORY: The development of TAG Heuer’s Calibre 11 movement

Felix Scholz1969 was a big year for many reasons. Man landed on the moon, the internet was born and the Beatles released their final album. It was also a hugely significant year for horology, with two revolutionary developments. The release of the first quartz watch, by Seiko, was the first. The second was the introduction of the first automatic chronograph movements, among which was the Heuer Calibre 11.

Today the automatic chronograph is ubiquitous, one of the most popular complications – forever associated with the high speed worlds of motorsports and aviation. But in the first half of the 20th Century, the self-winding chronograph was one of watchmaking’s greatest challenges. By the ’60s automatic watches were dominant, and outside of dedicated automotive, military or scientific applications, manually wound chronographs were increasingly losing ground against the more advanced automatics. The obvious next step was the race to develop an automatic chronograph. And with that, the challenge between the rival brands was on.

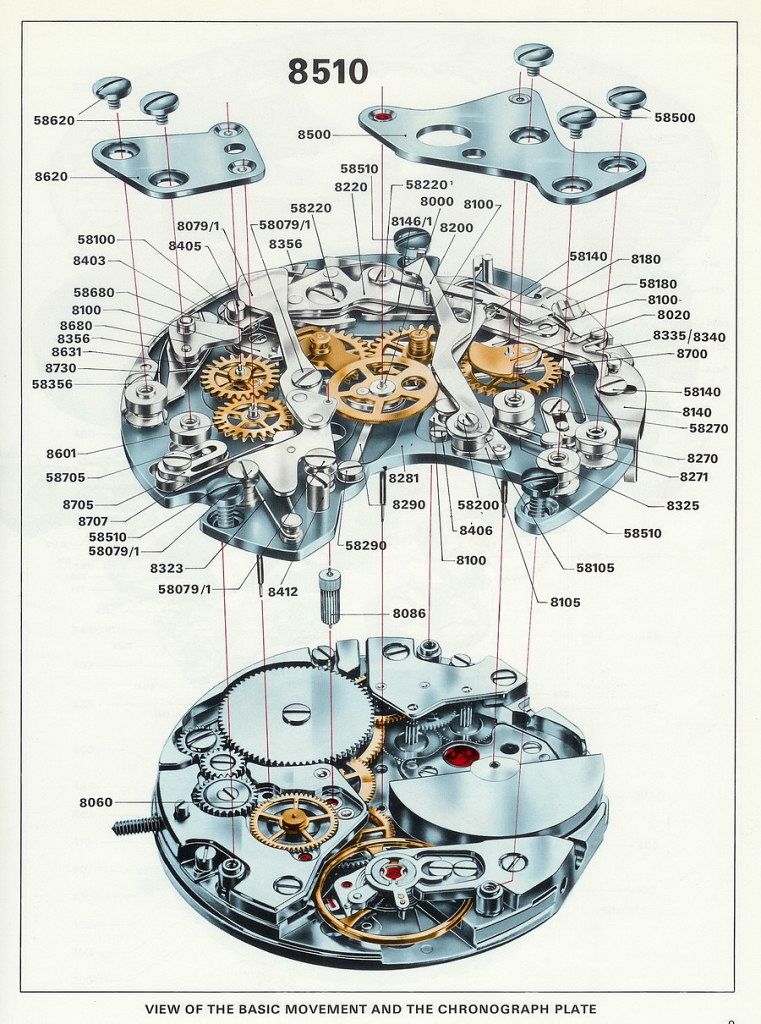

An industry leader when it came to precision timing and chronographs, Heuer couldn’t achieve something as complex and costly as an automatic chronograph on their own – and so, a top-secret partnership was formed between Heuer, Breitling, Büren (and later Hamilton) along with movement makers Dubois-Depraz. Together, these brands could share costs and expertise. Heuer and Breitling brought skills in making and marketing chronographs. Büren had particular expertise around micro-rotor automatic movements and Dubois-Depraz was an industry leader in making modular movements. Fiercely competitive though they were, the four joined forces in the mid-60s to work on the ‘Chronomatic’ movement, under the codename ‘Project 99’.

Of course, they weren’t the only ones pursuing the dream of the automatic chronograph. In 1962, Zenith weren’t particularly known for their chronographs, but that didn’t stop them working on their own high-beat column wheel chronograph movement. And further afield Japanese watchmaking giant Seiko (who were, at the time, consistently beating the Swiss in their own prestigious observatory tests of precision) were making strides towards an automatic chronograph of their own.

Things came to a head in 1969. In January, Zenith leapt out of the gate announcing their El Primero (translated as ‘the first’) movement, three months before the Basel fair (though it didn’t hit the market until October). The Chronomatic partnership announced their movement (you can read the report in this PDF of the 1969 Swiss Watch and Jewelry Journal) in March, and by the time of the Basel fair, the Chronomatic group dominated with their profusion of brands and models. Compared to the high-profile announcements of the Swiss brands, Seiko seemed content to launch their Speedtimer quietly in May.

In 1969 Heuer released three typically avant garde automatic chronographs in terms of their design: the unconventional Monaco (which was also the world’s first square automatic chronograph), the classic Carrera and the utilitarian Autavia (in black and white dial versions). The distinctive position of the winding crown on the left clearly indicates the presence of the new Calibre 11 movement. These models became iconic pillars of Heuer’s line-up, and pivotal to the brand’s continued growth and success.

The result of years of collaboration and research, the Calibre 11 is a movement that casts a very long shadow, playing an instrumental role in popularising the chronograph, and establishing Heuer as the masters of this sporty complication.

Find out more about TAG Heuer’s history with precision timing here.