Chopard L.U.C and the challenges of outgrowing a household name

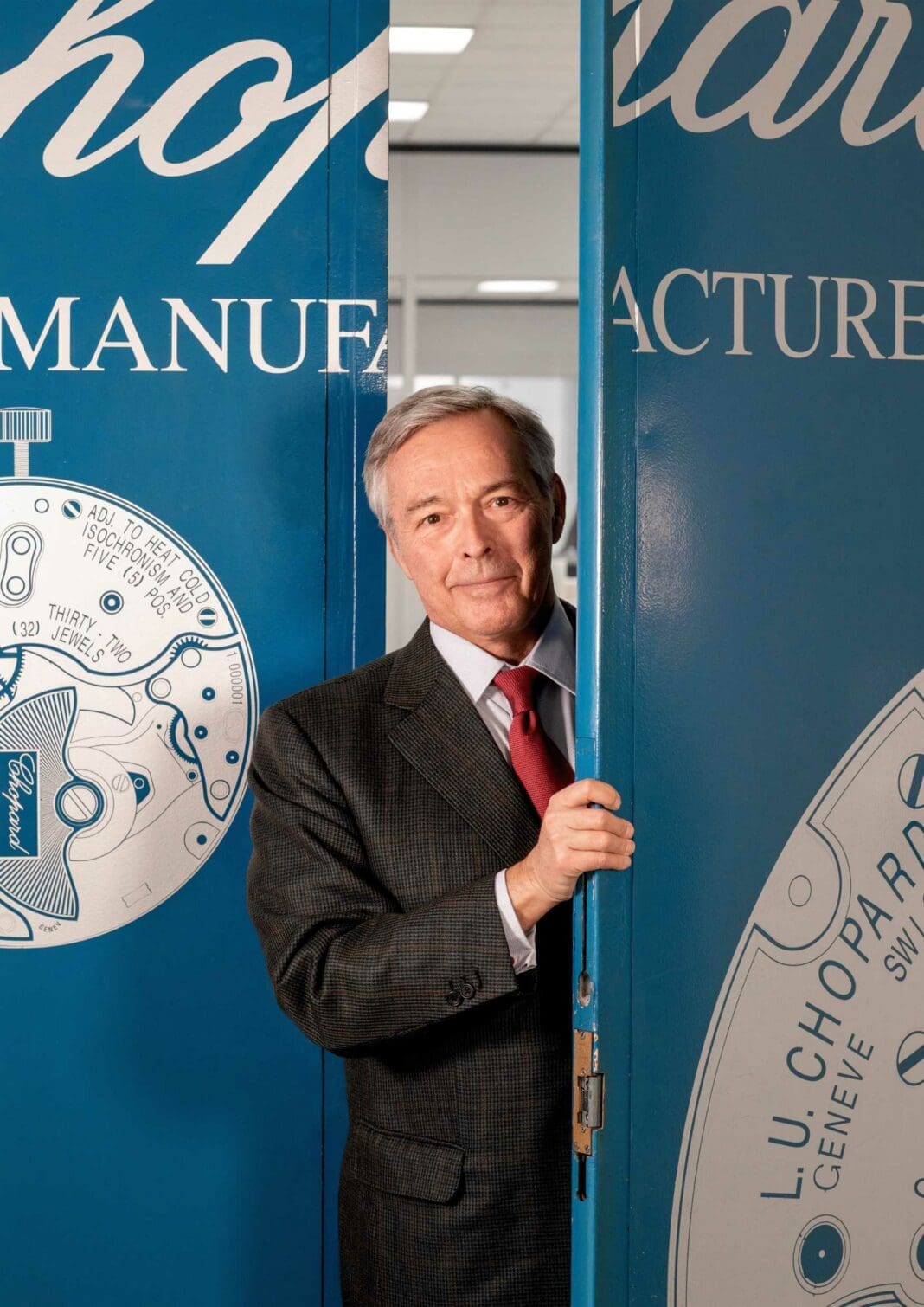

Borna BošnjakIf I asked you what attributes are necessary for a brand to be elevated to the echelons occupied by the likes of the holy trinity, I’m sure the answer would contain some, if not all, of the following: rich heritage, exceptional attention to detail, and unique, highly-involved complications. I needn’t name all the names that qualify, but I do wonder how many would include watches from the Chopard L.U.C collection in the watch world’s aristocratic high society. Not many, is my assumption. Figuring out why that is, however, doesn’t simply come down to L.U.C pieces meeting and exceeding the aforementioned criteria. With the help of Chopard’s co-president, Karl-Friedrich Scheufele, and as frequently misquoted from Christopher Nolan’s Inception, we must go deeper.

The origins

Louis-Ulysse Chopard was born to a farmer in the picturesque landscapes of the Swiss Jura. At a young age, Chopard realised that, rather than producing watch components that would be put together elsewhere and marketed for high profits by others, he could set up his own manufacture of precise timepieces. Thus, in 1860, at the age of 24, Louis Ulysse set up his own workshop in Sonvilier, quickly gaining respect for his work, eventuating in two high profile customers of accurate railway timepieces – Tir Fédéral and the Swiss Railway Company. The company went from strength to strength, carrying on in the Chopard family for three generations, before its eventual sale to German goldsmith and watchmaker Karl Scheufele III in 1963. Paul-André Chopard who headed the brand at the time could not find a successor in the Chopard family, and Scheufele was looking for a company that could produce movements for his Eszeha brand, rather than sourcing them from the likes of IWC, Jaeger-LeCoultre and Vacheron Constantin. The company was sold, remaining under Scheufele family leadership to this day.

In the years that followed, Chopard faced more hardship, this time in the form of the quartz crisis. Scheufele was faced with a choice – continuing to strive and produce the finest, most accurate mechanical timepieces, or to give the customers what they wanted – namely, quartz watches. This is how the 1976 Chopard Happy Diamonds collection came to be – with diamonds floating between two sapphire crystals, free to move atop the dial. The idea was a huge success for the brand and was followed by the 1980 release of the St Moritz.

The golden years of the quartz crisis allowed the brand to shift their focus from jewellery-oriented pieces in the years to come, partnering with the iconic Mille Miglia race and creating a watch collection that would become a staple in the Chopard collection since its 1988 introduction. Scheufele doubled down on developing the brand, deciding to return to the mechanical mastery of the Chopard brand of old. “I was convinced that the manufacture idea is really something to pursue, and most of all, for credibility’s sake,” Scheufele explains. Deciding to produce a shiny new in-house calibre, the brand set up an integrated manufacturing plant in Fleurier, with movements meant to rival top-tier brands. This was a risky move, namely due to the cost associated with such an undertaking and considering the safe success that quartz brought in the past. The movements were destined for a brand new collection, one that looked to honour the brand’s founder – L.U.C, named after Louis-Ulysse Chopard.

With humble beginnings occupying only half of one floor in a building owned by the Swatch Group, the L.U.C manufacture was completely top secret. Scheufele decided that Fleurier was the area ripe for watchmaking activity, thus far only explored by Parmigiani’s restorative workshop. Recalling a funny conversation with Nicolas Hayek of the Swatch Group after deciding to purchase the space, Scheufele gently pointed out that the “building is not in Zurich on the Bahnhofstrasse”, prompting Mr Hayek to sell at a decidedly more reasonable price. Almost immediately after its establishment, the Fleurier manufacturing plant bore fruit, and how juicy it was. The Calibre L.U.C 96-01 was, and frankly still is, the stuff of dreams, receiving a Poinçon de Genève, while the L.U.C 1860 watch that housed it won the Watch of the Year by Montres Passion. Standing mere millimetres in height thanks in part to the 22k micro-rotor, it featured twin barrels for an impressive 65-hour power reserve, a Phillips terminal curve to the balance spring, while being decorated to the nines with Geneva striping applied with abrasive wheels, black polished swan neck regulator and screws. Omitting to mention the mirrored hand-applied anglage and screw countersinks would be sinful in this case, as it’s worthwhile to remember that this was 1996.

Haute horlogerie hallmarks

Chopard and Scheufele didn’t rest on their laurels. What followed is to this day one of the most impressively packed movements I’ve come across – the 1998 release of the L.U.C Quattro. The 38mm diameter and 9.8mm height would suggest a standard-issue dress watch, but when you turn it around, the Calibre 1.98 will stun you with its dual stacks of double barrels and finishing at the same level as its 96-01 predecessor. Scheufele places it as a highlight of the brand that didn’t enjoy as much success as it deserved. “We basically came out with the first four-barrel movement. The whole thing was chronometer certified.” It’s worth noting that chronometric performance applies over its entire nine day power reserve.

The following years saw no signs of stopping from Chopard. From 2003 to 2013, the L.U.C collection saw the introduction of a myriad of complicated and innovative calibres – an inhouse tourbillon, perpetual calendar with moonphase, and the Calibre 05.01-L, comprising those with the four-barrelled set-up of the Quattro for the brand’s 150th anniversary. I also can’t omit mentioning the L.U.C Strike One, chiming the elapsed hours, created for the 10th anniversary of the Fleurier manufacture, nor the highly innovative L.U.C 8HF, offering 60 hours of power reserve from a single barrel, while beating at 8Hz (57,600 bph).

Today, L.U.C’s collection includes more than 50 different pieces, ranging from simple three-handed watches powered by the L.U.C 01.01-L calibre, to incredible creations such as the Full Strike Sapphire. While those certainly occupy two extremes, there are some real gems across the scale within the four sub-collections. The stand-out for most will be the XPS 1860 Officer, with its incredible hunter caseback and honey-related motifs, while an early entrant into the collection, the Quattro, is still present, with its seemingly unending chronometer-certified power reserve and Poinçon de Genève certification.

Time to focus

Scheufele talks about Chopard with passion, especially when it comes to their striving for complete independence. “It’s purity, it’s credibility, it’s the true manufacture idea,” he explains. “Swatch Group was trying to choose its customers, then the famous ruling came in where they had to continue to supply movements until a certain time, and this totally convinced me. I had no more doubts. For me, it was about independence, and the fact that I could actually create the movements that I really wanted to have, with all the specifications that we wanted to have.”

The only collection that still depends on ETA movements is Mille Miglia, though Scheufele admits “of course, eventually I would like to produce 100% of our movements.” Having created Fleurier Ebauches in 2008, the manufacture produces “40,000 movements for our Happy Sport Collection, and more importantly now, the entire Alpine Eagle collection is equipped with these movements. All of this would not be possible without the fi rst L.U.C.” While the revenue generated from L.U.C only represents at most 15% of all Chopard watches, their development was clearly paramount to where the brand is now.

To make a motoring analogy, L.U.C creates the supercars with technology that eventually trickles down to the more accessible consumer market. But could L.U.C modify their strategy, and just focus their attention on the supercars, allowing Chopard to take up the slack left by the more entrylevel pieces in the L.U.C collection? At the moment, L.U.C covers a really wide price bracket and, while all the watches in their portfolio are worthy inclusions, I wonder how much more recognition they’d enjoy if they concentrated on only the Geneva Seal portion of their collection, as there is a clear divide between those and the non-hallmarked pieces. Combine this with Scheufele’s perfectionism, and we’ll have a brand that will finally get the recognition it deserves. “If a detail is not right, I will just not release the watch. I don’t really care, if it takes six months longer,” Scheufele remarks.

Finally, of course, there is the marketing side of things. Chopard isn’t the only brand that has experienced this sort of conundrum. Just think back to Grand Seiko’s removal of the Seiko script from their dual-signed dials, and the distinction the corporation now makes between the two brands. Chopard’s beginnings were top secret: “No branding, no signage, nothing”, Scheufele recalls. Although the Chopard brand gets plentiful exposure, even now, he admits that “[he has] probably been too discreet about the whole thing”. While an increased presence in magazines and billboards is sure to bring more customers, this approach may stop L.U.C being the if-you-know-you-know marque that collectors love. Either way, with a long, innovation-filled history to guide them, L.U.C’s future is looking very bright.