Beheadings, vice and a massive harem: The wild inspiration behind the Cartier Pasha

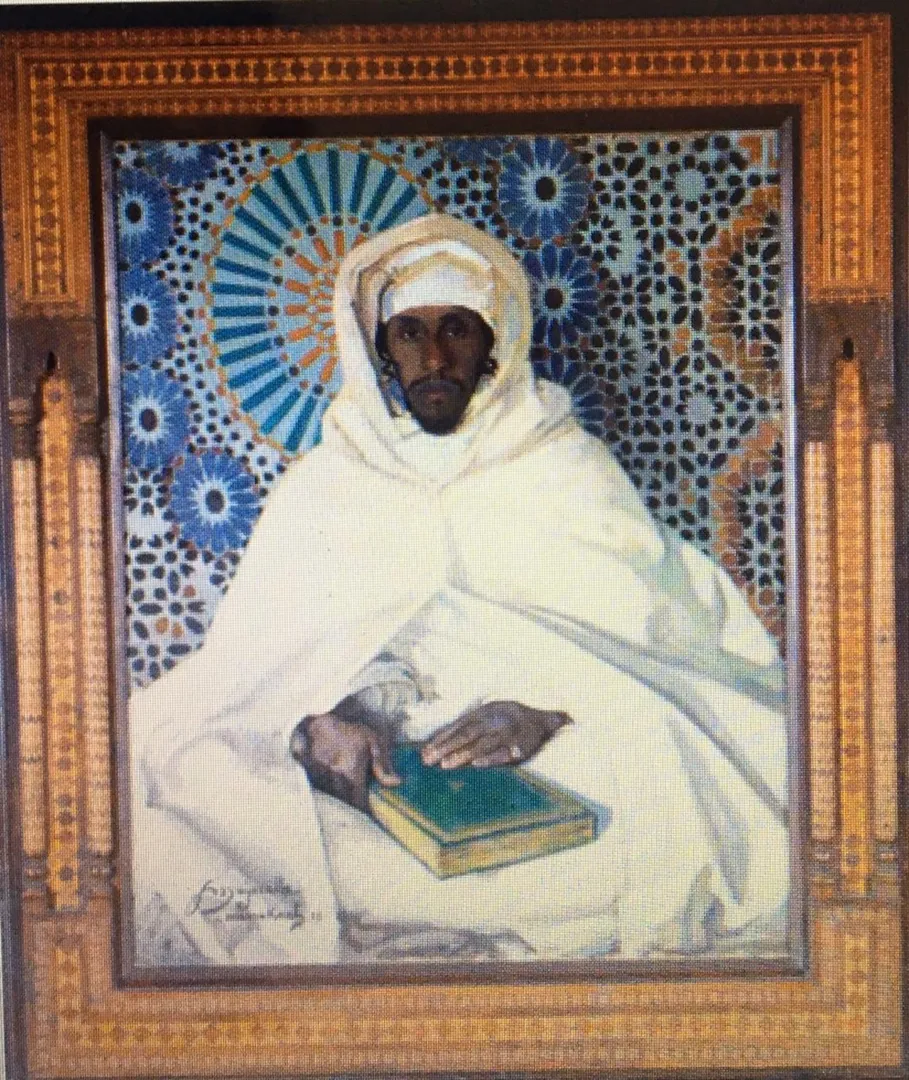

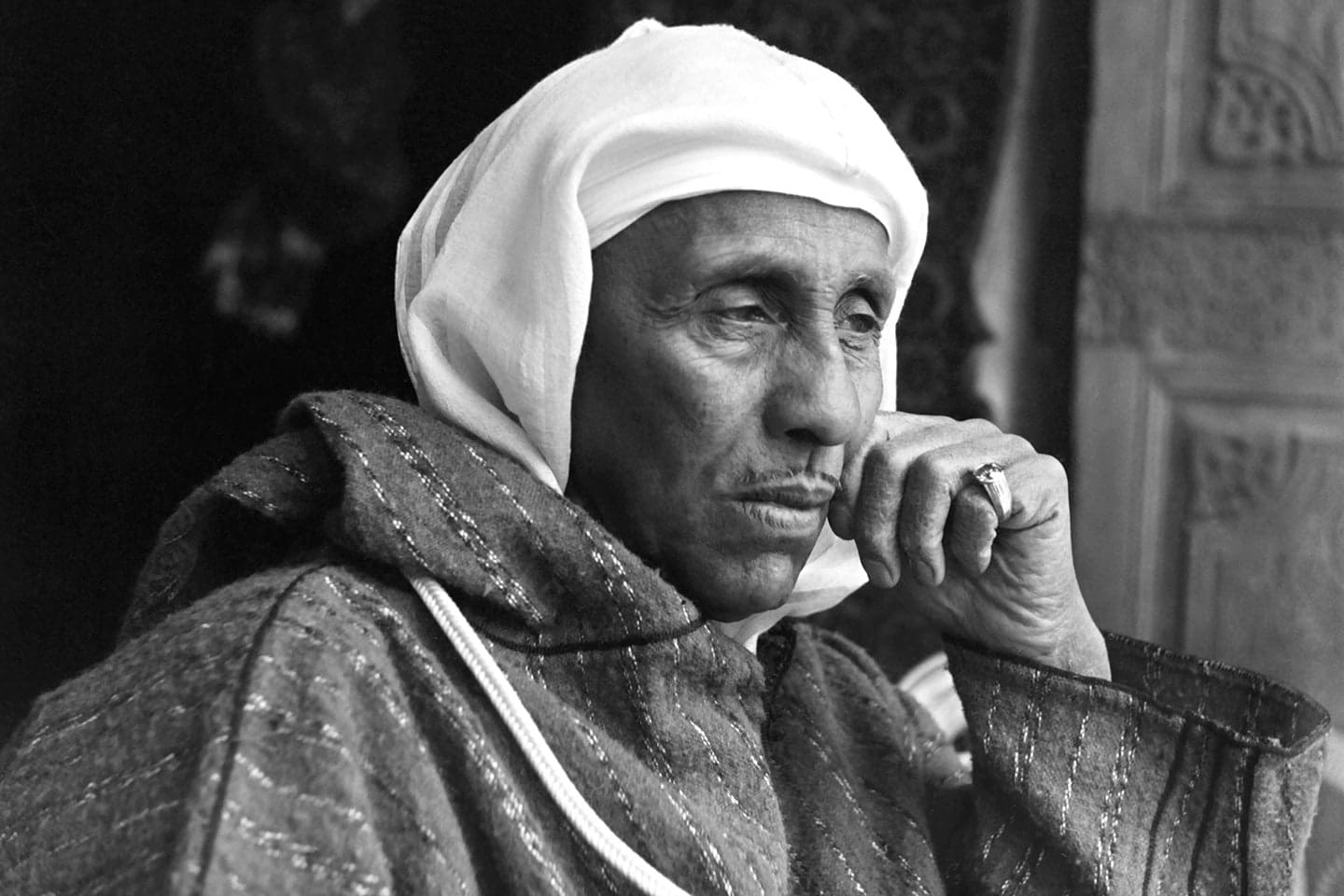

Luke BenedictusThe Pasha of Marrakesh enjoyed a life of barbaric splendour. During the first half of the 20th Century, Thami El Glaoui rose from a tribal warlord in the Atlas Mountains to become one of the richest men in the world. His colossal wealth stemmed from interests in Morocco’s salt and mineral mines compounded with the huge tithes he demanded from the harvest of olives, almonds and saffron. But the Pasha profited by nefarious means, too, maintaining a stranglehold on the local prostitution and drug rackets.

Predictably, his vast riches led to commensurate levels of debauchery. El Glaoui’s personal harem included 150 women, while he hosted banquets of fabled ostentation with a guest-list that included the likes of Winston Churchill and Charlie Chaplin. “To his guests Thami gave whatever they wanted,” wrote Gavin Maxwell in Lords of the Atlas, “Whether it might be a diamond ring, a present of money in gold, or a Berber girl or boy from the High Atlas.”

El Glaoui was also utterly ruthless. His elevation to serious power came after he sided with the French against the Moroccan sultans and was subsequently rewarded with free rein to govern Marrakesh and the nation’s south. He ruled with the merciless flair of a mobster kingpin. Shortly before attending the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, for example, he ordered the severed heads of his enemies to be mounted on his palace gates.

In short, El Glaoui was a man used to getting what he wanted, which is where Cartier comes in. For the Pasha had a curious longing for a watch that would enable him to tell the time while soaking in the bath. So he got in touch with the French maison…

Pierre Rainero, Cartier’s Image and Style Director confirms the tale and explains how El Glaoui’s patronage of the watchmaker became the convoluted inspiration for one of brand’s future releases. “The Pasha of Marrakesh, El Glaoui, bought one of Cartier’s first waterproof watches in the 1930s,” Rainero says. “So when we launched this watch in 1985, we had the idea to name it ‘Pasha’ as a tribute.”

The Cartier Pasha certainly shared its namesake’s decadent swagger. Defiantly bold, the watch was an idiosyncratic design statement. “It was a total surprise at the time,” Rainero agrees.

With its 38mm diameter, the Pasha was a disarmingly big timepiece for the 1980s. The dial featuring a square inside a circle framed by four Arabic numerals was relatively straight-forward, but the central lugs attaching case to the strap offered a retro flourish. Indeed this was a difficult watch to pigeon-hole full-stop. Not only did it come with a diving bezel, but there was also a quirky crown cover attached to the case with a small chain link. Such functional details suggested a sports watch of sorts. Except that, the first model was made of gold – a luxury not in keeping with the sturdy pragmatism of a standard diver.

Not that this watch cared what you thought. It was unapologetic in its brazen disregard for horological convention with some versions. An early advertisement trumpeted this assertive spirit. “Pasha,” the copy read. “The powerful new watch for a powerful few men.”

In fact, this male-skewed intention didn’t last. “When we launched it, because of the size, it was obvious that it was a watch for men,” Rainero says. “But what we thought of as a masculine object, became very quickly a trophy for ladies.”

Adopted as a unisex model, the Pasha soon became a 1980s classic and has since enjoyed a variety of incarnations leading to this year’s upgrades that boast antimagnetic in-house movements. Along the way, there’ve been tourbillons, moonphases and perpetual calendars. The Pasha has been smothered in diamonds, democratised in steel and, in perhaps the most memorable iterations, masked with a grill protecting the dial like a deep-sea diving helmet.

When the original 1980s model was being developed, Cartier called upon Gérald Genta, the legendary watchmaker and designer responsible for the Patek Philippe Nautilus and Audemars Piguet Royal Oak who effectively kick-started the boom in luxury sports watches. “He developed a completely new movement for us,” Raniero admits.

Genta’s involvement in the Pasha may have been limited to the mechanical side, but the context of his broader work remains instructive. The Nautilus and Royal Oak originally got a sceptical reception before gaining widespread acceptance. Yet, the Pasha remains an edgier proposition. It’s divisive like any truly singular piece of design and continues to provoke extreme reactions among watch-lovers ranging from adoration to bafflement.

History views the watch’s namesake less kindly. Cartier’s watch may evoke something of El Glaoui’s lethal glamour, but the ruler’s legacy is increasingly contentious. The man who caroused with Churchill and Roosevelt in his heyday, is now widely scorned in Morocco as a traitor who double-crossed his nation to the French for personal gain. Cartier’s timepiece may trade on the Pasha’s exotic pomp, but El Glaoui’s name is commemorated less fondly elsewhere. His actions would come to inspire a new verb in French – “glaouiser” means “to betray”.