INSIGHT: A visit to Montblanc’s Le Locle and Villeret watchmaking factories

David ChalmersLooking at Montblanc’s recent list of hits – from the Meisterstück Heritage Perpetual Calendar to the Tourbillon Cylindrique Geosphères Vasco da Gama- it’s easy to see why the brand is wearing the yellow jersey in the race for the best ‘contender’ brand currently. But the truth is that these impressive watches haven’t emerged from a vacuum, or by some well-timed stroke of luck. Sitting at the heart of the brand is one of the oldest and most traditional names in watchmaking, being Minerva, which traces its origins back to 1858 when it was founded by the Robert brothers.

A visit to Montblanc’s two principal Swiss locations- Le Locle and Villeret- reveals a combination of cutting edge and traditional watchmaking methods. High tech CAD and testing goes hand-in-hand with haute horlogerie pieces polished over the course of many days using no machinery – only the stem of the Gentiane plant. If you’re not sure what this is, don’t worry – we’ll explain its mystical properties shortly.

The arrival of the dynamic Jérôme Lambert as CEO in 2013 has seen a creative renaissance from Montblanc, and while Monsieur Lambert is based in Hamburg, he of course keeps a close eye on the watchmaking activities to the South. One of the first changes made by Lambert was to reorganise the two sites. Le Locle looks after the design, technical department, cases and dials, testing and assembly, while their Villeret facility is responsible for movements and Haute Horlogerie.

We were lucky enough to spend a beautiful winter’s day in Switzerland exploring the traditions and technology of Montblanc

Le Locle

Le Locle rightly regards itself as one of the epicentres of Swiss watchmaking, despite being the third-smallest city in Switzerland. Zenith is here, as is Ulysse Nardin. On the same street as Montblanc is the vast Tissot factory, the original building of which dates back to 1853. The main Montblanc factory here was bought by the company back in 1997 when they began making watches. Turning a 19th century villa into a state-of -the-art facility is a renovation nightmare, and Montblanc have cleverly circumvented heritage restrictions by building their factory into the hill under the building.

But before we head inside the main building, let’s take a quick trip across the road to the technical department.

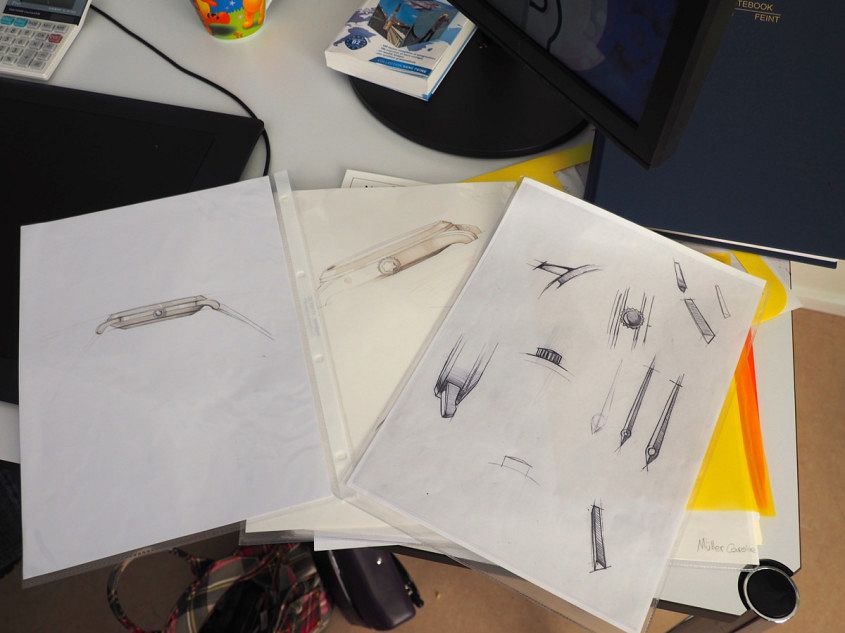

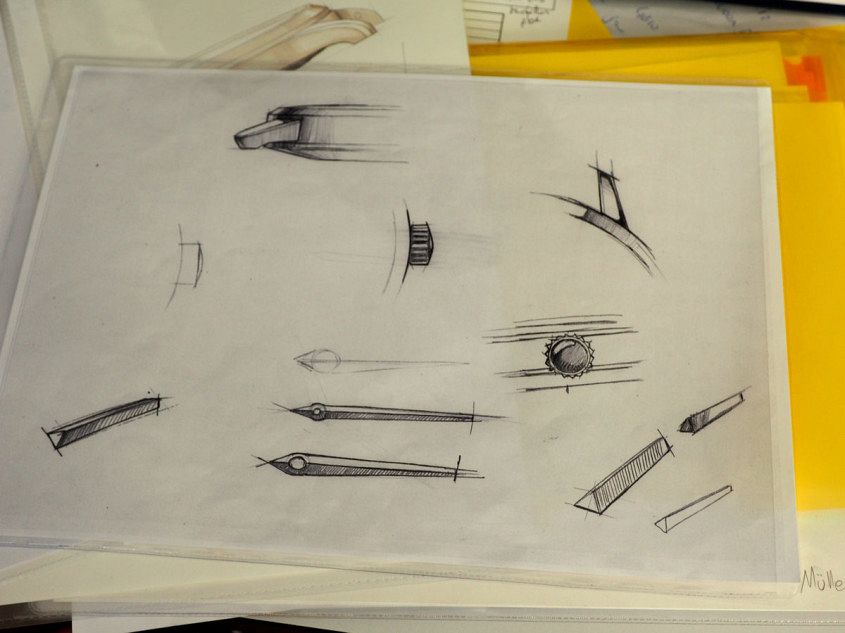

The technical team is made up of one part designers and one part industrial engineers. It’s vital that a new design can be made into a prototype that looks exactly like the concept drawing- and that these concepts work as well on the wrist as they do on screen. This may seem like a simple task, but when you consider the role that light plays in highlighting certain aspects of a watch’s design, you start to see the challenge for the team. The designers have to anticipate what their drawing will look like in three dimensions well before it’s ever made.

Once a drawing is complete, the design is then passed to the engineering team who transform the design into the CAD system, from which a 3D printer can make a wax model.

It’s from these models that parts are eventually made and then homologated. For those of you who aren’t up on their obscure Latin verbs ‘homologation’ is where the design is tested in the metal before its signed off and enters production. It is the last chance for the team to check that the design has been successfully translated from paper to screen to wax and finally into metal.

Back in the main building it’s a hive of activity with watches being assembled and tested. While some parts are made here in Le Locle, many are produced at Montblanc’s dedicated production line at ValFleurier, a company that is one of the secrets to Richemont’s success. Rather than have ValFleurier make parts for the various Richemont family members, each brand designs and manages its own production line within the ValFleurier manufacture. This allows smaller brands to achieve economies of scale, yet retain their own sense of identity and uniqueness.

The majority of watches being assembled here use movements with Sellita or ETA bases. The manufacturing strategy for Montblanc is to focus on developing its own complication modules (e.g. chronograph module) to sit on top of these base movements for the majority of the range. The fully-developed in-house movements are reserved for the top-end of the collection.

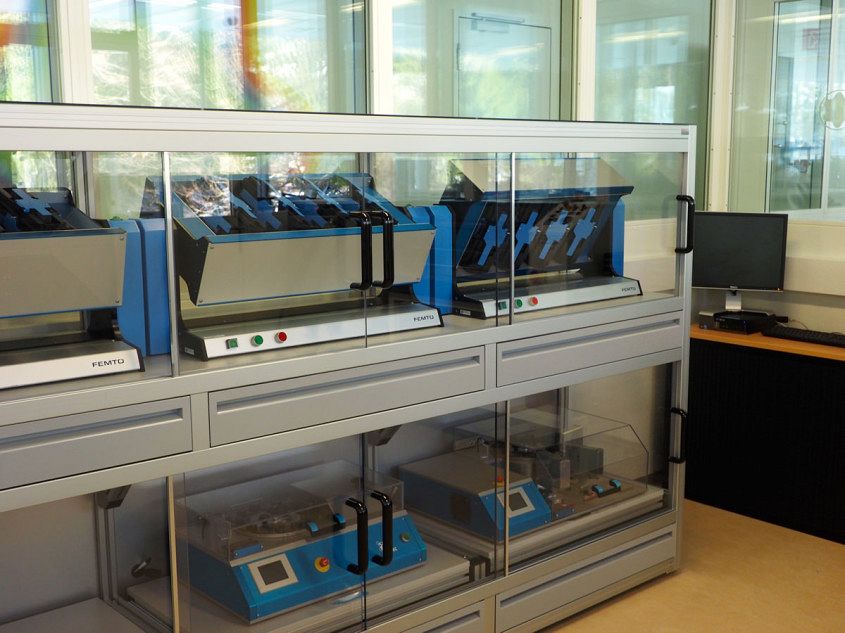

The final aspect of work here at Le Locle is quality control, the pinnacle of which for Montblanc is the 500 hour test. Every watch with an in-house movement, or from the Chronometrie collection must endure a battery of five tests:

- Winding Performance and Assembly Control (4 hours)

- Continuous accuracy control (80 hours)

- Function Testing (336 hours)

- General Performance (80 hours)

- Water Resistance Test (2 hours)

The idea behind the 500 hours test is to simulate the first year of ownership and ensure that once a watch heads out the door, it doesn’t come back until it’s first scheduled service, several years later.

Villeret

An hour drive away is one of the jewels of Swiss watchmaking, Montblanc’s factory in Villeret. This is the home of the legendary Minerva, one of the leaders in precision timing. The heritage brand was acquired by Richemont in 2006 before being transferred across to Montblanc.

It’s a beautiful view from the Villeret building and a meaningful one. See the house with the red shutters across the road from the factory? That is the very first home of Minerva from way back in 1858. Yes, in the course of 157 years, the company has moved five meters across the road- that’s it.

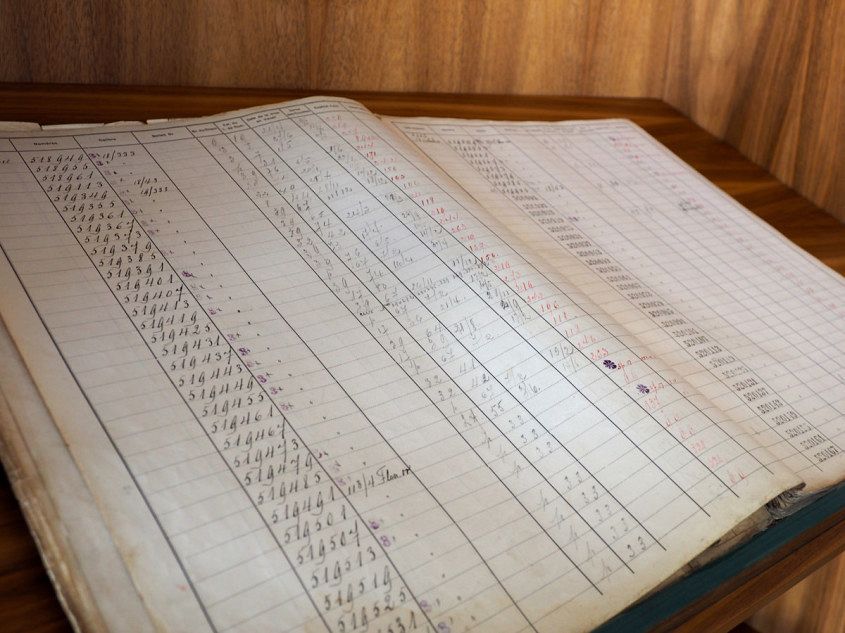

One of the special aspects of this factory is that it’s had continuous production since it began, meaning that the production records, accounting records are all here and all intact, all the way back to the very first watch.

There is also a treasure-trove of original parts stored here, the sort of heritage that most brands can only dream of.

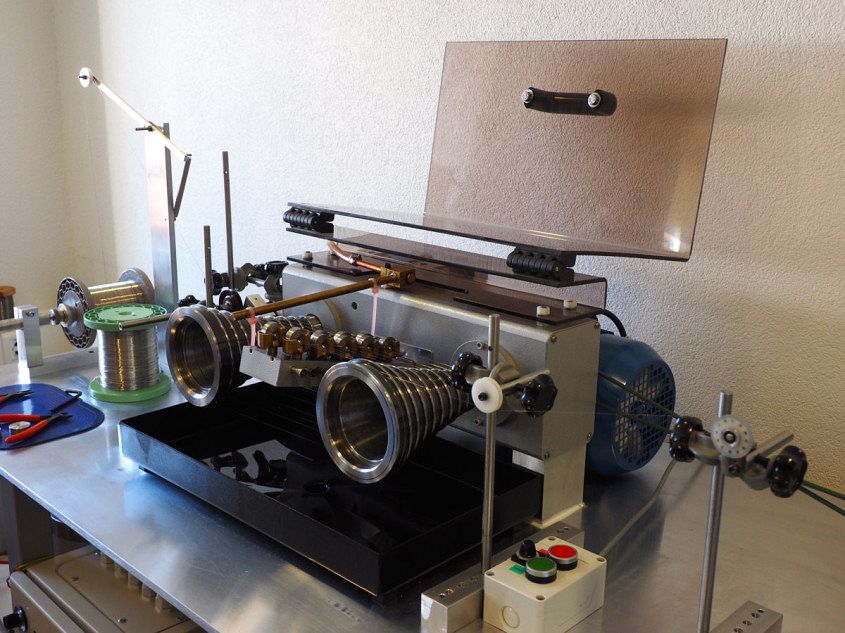

But Villeret is not just a dusty museum – it’s the home of Montblanc’s haute horlogerie collection and movement know-how. All movement development is performed here at Villeret – that goes both for the modules and for new movements. And they do things properly at Villeret – it can take five years to develop a new movement, and up to two to develop a new module. Other components, such as base plates are also made here. And boy, just look what kind of a machine it takes to cut a base plate…

Every Montblanc Collection Villeret watch begins with this machine, because Montblanc stamp all base plates using the historic equipment – an important way of keeping the links to the past range of Minerva watches. Not surprisingly, OH&S rules don’t allow the heavy presses to be used regularly, so every few months they are turned on and run for a few days to produce the quantities required.

And this is symbolic of the way that watches are made at Villeret; there are very few machines used here, and the few that see active duty are typically traditional heavy cast iron machines that have been in use for decades.

The main workshop at Villeret is where the parts are both made and finished- and finishing the parts is where the magic happens. You see the angles are cut in a way that no machine can do- not because this makes a difference to the decoration, but because this is your proof that the part was finished by hand.

To give you an idea of the level of craftsmanship, it can take one skilled watchmaker a full week to hand polish a tourbillon bridge.

Look carefully above and you see that the watchmaker is polishing a component using a piece of wood from the Gentiane lutea plant that we mentioned at the start of the story. That’s it leaning up against the wall below. It’s used by Montblanc because it has the perfect structure to polish metal without scratching it. Oh, and the Swiss also make a liquor out of it. Truly a useful plant.

All this effort may seem like overkill, but when you see the magnificent finished product you can see the difference. Take a closer look at the movement on the bench below.

Simply beautiful

Montblanc is a brand on the march. And while a lot of this rapid progress is undeniably down to the whirlwind personality of Jérôme Lambert, it’s progress that would be simply unthinkable if they did not have the tradition, skills and knowledge of the Villeret facility to draw on. Combine that with the cutting edge production capacity of Le Locle, and it’s easy to see why Montblanc is a name on many’s lips in the watch world right now.